Paula, Ann, and the Octopus

Paula smells the octopus first. It is a minus two-foot tide on the rocky reef in front of Nanwalek, a Sugpiaq village of about 200 people on the lower lip of Kachemak Bay. The 10-year-old circles a barnacle-covered boulder and sniffs, while her mother, Ann Evans, kneels in front of another large rock. In search of a favorite subsistence food, mother and daughter are examining the wet pockets beneath large boulders in the midst of the otherwise dry beach. Twiggy and Squatchy, their mutts, loop-de-loop across the reef.

Ann walks over to Paula’s rock carrying her octopus stick, a four foot-long spring steel rod. “It’s pretty strong,” Ann agrees about the smell. The salt-fresh tang of low tide is thick in the air, but these two sense something different. Ann jabs the stick into the wet gravel beneath the boulder, then she lets go. After a second or two, the free end of the rod begins to wag. A feisty octopus on the other end has grabbed hold of it. Paula’s nose was right.

The school secretary for Nanwalek’s single K–12 school, Ann regularly harvests octopus during extreme low tides. Elders taught her, she explains. Paula loves to eat it pickled. Sometimes Ann will make a traditional-style rice bowl, piling octopus, seaweed, salmon eggs, smoked fish, and onions onto rice. That is her husband Tommy’s favorite.

Ann is one of nine children. “We grew up eating, breathing, and living all of this,” she says, and she continues the traditions with her three children. Tessie, 13, is deaf. Because sign language doesn’t have a word for bidarki, a tidepool shellfish that is a favorite subsistence food, Ann made one up. She holds one cupped hand on top of the other, replicating the animal’s boat-shaped shell. Ann’s oldest is 15-year-old Evan. She recently posted a photo of him on Facebook squatting next to a fresh seal carcass. “Today our son Evan Troy Evans is a man,” she wrote, with lots of heart emoticons sprinkled in. “He caught his first seal. We are so blessed.”

Not far from Nanwalek, you can find pictographs on rocks of killer whales, seals, and sea otters. The Sugpiaq people have been here for thousands of years, living a rich life off the bounty of the sea. In a handful of generations, this community has transformed from what was likely a seasonal camp to a Russian fur trading post, then a fish cannery town, to a modern, year-round village with trucks, internet, and Amazon delivery.

Local elders have seen so many changes, including the 1989 Exxon Valdez oil spill that slicked Nanwalek’s beach with crude and left residents fearful of contaminants for years. And then there’s the decline in some of the subsistence species that started before the spill; a cascade of collapse in populations of sea urchin, sea cucumbers, crab, shrimp, and clams. More recently, Ann and others have noticed bidarki are smaller and harder to find. Now with climate change, Ann is concerned about other changes she is noticing in the land and sea around her.

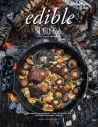

Even so, at a weekly elders tea in the tribal center, a bounty of traditional dishes are on display: baked silver salmon, clam fritters, sea lion steaks, seal, trout, and salmon eggs mixed into mashed potatoes. Seal oil is the main condiment, and elders pass a jar of the clear yellow oil between folding tables. In the sometimes stormy seas of rapid cultural, social, and environmental changes, traditional foods are a critical anchor.

The beach hisses with the sound of thousands of barnacles closing. The dogs crunch mussels with their teeth, devouring shell and all. Ann and Paula crouch at the boulder, alternately working the stick and stopping to watch the space beneath the rock. “You smelled that right quick,” Ann commends. “Good job, baby girl.”

The traditional saying goes: “When the tide is out, the table is set.” Few dinner options in the intertidal are as fascinating as the octopus, famed as this invertebrate is for learning to unscrew jar lids or escape, Houdini-like, from captivity. And they can change color in seconds to camouflage or just reflect their mood. Of the 300 or so species of octopus worldwide — and the more than half a dozen that live in Alaska waters

— the giant Pacific octopus is the largest. In their three-to-five-year lifespan, they can grow to 100 pounds or more.

Amikuq is the word for octopus in Sugt’stun, the traditional language of the Sugpiaq people. These animals are known to be highly individualized. Some are bold, others shy, quiet, or curious. Charles Moonin, a local elder who has been harvesting octopus since he was a child, said that the last one he collected pounced out from beneath a rock and looked him right in the eye.

Ann and Paula’s octopus isn’t making a showing, so we move on in search of bidarki. Ann will boil these shellfish in salted water and turn them into a kind of gravy or add them to the rice bowl. She hands Paula a knife and encourages her to pry one off. Paula does so deftly. “Alright! Look at you!” Ann praises.

The tide has turned, and Paula eyes the dry isthmus connecting us to the mainland, which is getting narrower every minute. Like most American kids, Paula has seen the latest Disney blockbusters. She likes to play four-square during recess and loves math and P.E. But at home, Ann teaches her beading and how to weave baskets. Paula is the next of many generations of Sugpiaq people holding the tenuous thread connecting those who came before — and I’m pretty sure this soft-spoken 10-year-old understands the weight of this.

We circle back to the rock Paula sniffed about an hour ago. Ann shoves the metal rod under the boulder again. Paula plants herself on the opposite side of the boulder, watching to see if the octopus tries to make a quick getaway. Ann grabs a bottle of bleach from her backpack and squirts a bit under the rock. The bleach is an irritant (some people use Coke, others use coffee), and after a minute of prodding, a tomato-red arm, about two feet long, emerges from under the rock and breads itself in small bits of white shell.

Ann grabs the animal and plops it on a low, dry rock. It is a mass of constant movement, every bit of it sliding against the other. She flips it over and cleans it quickly with her knife, severing the cantaloupe-sized head from the arms, turning the mantle inside out like a bag, and cutting the viscera away with a few quick strokes. She places the guts in a neat pile on the beach next to the boulder. A sign of respect, Ann explains. Paula smiles.

After Ann puts the octopus in a plastic bag, we head back to the mainland. We’re just in time; the water is calf-deep and rising steadily. The reef will disappear in a few hours, changing everything. But the octopus will taste just like it tasted to the people who came before. This is a reminder that food is not just food. It is culture. It is history. It is place. It is a mother and a daughter together on the beach sharing the same keen sense of smell.

> Thanks to the Alaska Experimental Program to Stimulate Competitive Research (Alaska EPSCOR) for help on researching this story. Learn more about what they do at alaska.edu/epscor/