Fish Camp

The Origins of Dinner

The cork line thrums as we approach the net, close to shore. We’re three hours into a big ebb tide sweeping down Cook Inlet and around Kalgin Island’s north end. The current runs hard. Dad inches the skiff forward as I lean over the bow to hook the cork line, hard like rebar from the tension, with a gaff. My guts feel squashed up to my throat by my position on the gunwale. I grip the cork line and slowly pull it toward my chin and up over the bow. It lands—snap! Flattening my torso against it to hold it in place, I pull up sea-green mesh hand over hand until the lead line finally appears from the murky depths. There I hang for a couple of seconds, biceps burning, struggling for breath; it’s hard to expand my lungs at this awkward angle. With one last reserve of strength, I heave the lead line over the bow, so the boat is sandwiched between the net and the water’s surface. Now, we can pull ourselves along the length to pick our salmon.

When most people—Alaskans as well as Lower 48-ers—hear the term “fish camp,” they typically think of a slowly turning fish wheel and bright salmon drying in strips on a rack under the midnight sun. My family’s fish camp on a bear-free island is much different. Nearly 60 years ago, my parents—Dad, an outdoorsman from Kansas, and Mom, a music teacher from New York—borrowed money from a cannery and began their newlywed life as commercial salmon setnetters. They fished from small wooden boats, lifting heavy wooden kegs across the gunwale each day, picking slippery kings and cohos and sockeyes from tangled mesh. Regulations were minimal and their life revolved around the tides and weather.

Fast forward to today, when our family still spends part of each summer at fish camp, with my brother, Eric, and his wife now running the show and the rest of us working as support crew. Some things have changed dramatically: technology and the politics of fishing. But many things have stayed the same: food shopping in bulk before the season starts, the pure physical labor of pulling nets and picking fish, cutting and hauling firewood, fixing outboards, washing dishes and laundry by hand, grilling dinner on a beach fire. It's a rich way of life that shapes Alaska kids and families for the better.

A little about Kalgin Island: its northern face, the widest section, spans only four miles and lies in the center of Cook Inlet, nearly even with the mouth of the Kenai River. Just a few miles farther south you can almost hear someone holler across its narrow waist. Coves mottle its flanks like lace, and its hooked shin faces west toward Harriet Point. Kalgin has no volcanoes, like the west side of the inlet, no stores or bars like the east side, and no bears. What it does have are muskegs and mosquitoes and spruce beetle-killed trees; birds, beaver, foxes, and moose; blueberries, salmon berries, nettles for soup. And commercial fishermen. Fishermen who come every summer for salmon, hoping to refill the coffers, the jars, the freezers. Fishermen who bring their children and friends, seedlings for the garden, beer and pot and ragtag dogs. Fishermen with goals and dreams.

Summers at the beach were perfect for me as a kid, but too long and lonely as a teenager missing out on any kind of social life, summer camp, and pizza. By regulation, as setnetters, we only fished two twelve-hour periods a week, so the other five days I filled with beachcombing for tidbits of civilization in the ever-changing tideline, reading, writing letters, washing dishes or sweeping sand off the porch, and helping with projects like building a smokehouse or putting new tar paper on the roof.

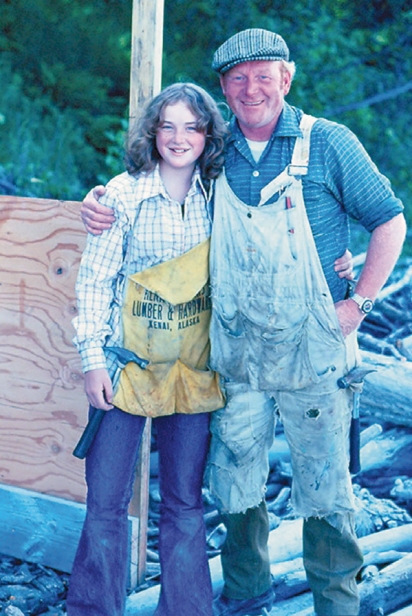

On fish days, Dad would wake me at 4:30 in his mock scary voice—"Sooosaaan, time to get uuup." Then in his sunny voice, he'd say, "Get up, get up, we've only got twelve hours to make it in!" Mom would have breakfast ready for us inside, the oil stove turned on if the day was drizzly, a small wood fire crackling in the 55-gallon barrel stove, even if a red sunrise was at hand. Dad and I would suit up in old shirts and hip boots and slickers and life jackets and cotton gloves. We’d pull the boat in on the running line and roar off to set our nets and make our year's only income on these few lucky days between 6 a.m. and 6 p.m.

Before Dad and I were fishing buddies, I’d begun learning at age seven with Mom. The salmon flopping and slapping, silently gasping for life on the bottom of the wooden boat scared me, and I’d cry and cringe back in the chute or up in the bow, as far away as I could get from the desperate, slimy creatures. I'd whimper for a few minutes, face buried in the lumpy orange life jacket wrapped around my neck and shoulders like a fat worm. Mom would cajole or order me back to the cork line to help her, and all would be well again.

The Island was, and still is, a treasure trove of freedom and self-sufficiency for our family. We walk on the beach and collect hundreds of agates every year, most going into jars on windowsills, a few hiding in coat pockets to be discovered in January, like lost jewels. We cover ourselves in bug dope, sometimes head nets, and hike up the hill behind the house, through the wildflower field with pungent chives crunching under every step. We swat mosquitoes while hacking with machetes at the overgrown trail through alders, around the beaver pond, across the big muskeg, all the way to Eric and Susan Lake. We found out years after we built the trail that our neighbors around the corner also had one from their house and called the lakes by other descriptors. Such is the nature of unnamed places.

On fish days, we work hard—to move the nets with the tides, to untangle the scaly reds and silvers from the web without damaging their flesh, to keep the salmon on ice until the tender picks them up at the end of the day or at dawn. Our backs get sore, jellyfish bits get flung into our eyes and sting, we smash fingers between boat edges. (Dad fished one summer with a broken index finger. Another time, he slipped in the boat and hit his head, and since there was no doctor handy, he held a frozen moose steak to his temple.) We sweat and shiver, pee in the bailer or over the side, and suffer through the itch we can’t reach under our life jacket. High wind and whitecaps toss our meager vessels around like toys; we stumble and curse, then right ourselves and continue. Those rare exceptional days when we catch hundreds (3,000+, once!), our grip goes slack trying to extricate the last salmon of the day; it’s all we can do to pitch the slippery catch one-by-one up into bins on the scow, bending and tossing, counting for the record.

Finally, back at the cabin, Coleman lantern hissing, we fall asleep mid-sentence at the dinner table, content in having completed an honest day’s work.