Baking to Terms

An Alaskatarian Decides to Hunt

I won a lottery this year. My name was drawn for a Unit 6C Federal Subsistence Moose Permit. I now have permission to hunt for a moose. In my community, it’s reason to celebrate, but I’m a newcomer to moose-hunting culture. Hunting has felt highly theoretical to me, until I stop to think about it too much, and then it feels a little terrifying. Sure, I’ve dispatched insects, rodents, the rare fish, but never something large, and never with a gun. Despite my chagrin about the obvious gender clichés, I’ve relished my role as the cook—the one who takes on the wild fish or game after it’s been transformed from animal to meat. I transform raw meat into food.

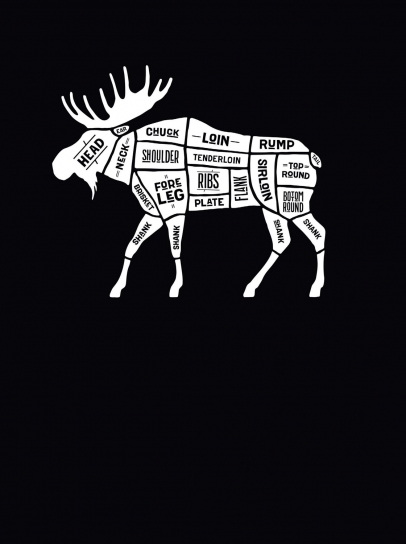

Last year, my partner Sam drew a permit. Although it was his first moose hunt, his son is a competent hunter, careful butcher, and accomplished game cook who helped the entire process go smoothly and swiftly. As Alaskans well know—it is a process. Hunting these giant herbivores often takes a team around here, sometimes even a pilot for a flyover the day before, an airboat owner/operator to transport the hunter and their team to the hunting grounds, and, more crucially, to remove the animal after it is killed and field dressed. There are cranes to lift the animal out of boats and onto vehicles, out of trucks and into processing areas. There is hanging and processing, packaging, and freezing. Through all of this, there’s lots and lots of sharing.

I have a couple of amazing women friends who successfully hunted moose via canoe this year. The high-tech ways are certainly not the only ways. The lottery is gender blind, just as it’s blind to ability or proclivity. I had never thought to enter before, because I am not a hunter. But lately, I’ve been convinced that it’s nearly a responsibility to participate. We live in a town that isn’t connected to the outside by road. All of our food is flown or barged in. This winter, given our governor’s disregard for rural Alaskans, we will not even have a ferry connecting us and our cars to the road system. Moose hunting is about food security.

Moose were originally brought to Cordova to provide a local protein source in the late 1940s. According to local historian Dick Shellhorn, from the original abandoned calves transplanted in the Copper River Delta—two cows and a bull—the local population grew and thrived, providing over 5,000 animals to the local community over the following decades.

Late this summer, we took stock of the freezer and were pleased to find lots of room. We’ve been successful in eating and sharing the moose. Most days, we eat plant-based meals, but we feel nourished and grateful when we do make a meal of moose. Since I have been mostly vegetarian (I say Alaskatarian because I eat wild fish and game) for a couple decades now, when I do think about what to make with game, my mind immediately travels to childhood family meals. I want to make the lamb dishes my Syrian grandmother used to cook. I want to make comfort food.

As golden light puts a fall tint on red fireweed leaves and highbush cranberries, my mind travels to butternut squash. I have an old favorite cookbook by celebrated author Carol Field. Called In Nonna’s Kitchen, it’s a collection of stories and recipes from Italian grandmothers. Maybe because I learned to make tiramisu from a friend’s nona in Liguria, or maybe because this book was one of the first with a combination of narrative and recipe that I discovered, I carried it with me through crisscrossing cross-country moves before finally staying put in Alaska. I couldn’t find it the other day, but I didn’t need to. I’d internalized the recipe at some point—a butternut squash and leek crostata.

Along with the requisite target practice, gear gathering, and planning, I’m cooking my way through the freezer’s last moose meat as a meditative preparation for my first hunt.