Winter in the Grocery Aisles

Musings About 90-Year-Old Receipts

After living in Alaska for a few years, I have learned to settle for kale or cabbage instead of baby spinach. I have stopped plotting my weeks’ meals precisely and I now go to the grocery store without a plan. At first, this more spontaneous approach felt haphazard. I grew up in a Lower 48 home with a mother who carefully calligraphed a week of meal plans and grocery lists on Sunday night. We made a weekly grocery trip (or two) and the receipts from those trips read like reiterations of my mother’s lists.

Most produce must make its way thousands of miles to Alaskan store shelves. Indeed, 95 percent of the food purchased in Alaska comes from out of state. A single, minor disruption in the supply chain can leave shelves bare. Even when produce makes it to Alaska without delay, the quality can suffer from the long journey through freezing temperatures.

Now, my grocery receipts read erratically, especially in winter. In January, I may walk into the store with all the best intentions to come away with pounds of beets, onions, parsnips, and carrots for a hearty vegetable borscht but leave instead with ingredients for mac and cheese and two and a half pounds of grapes. With luck, the grapes aren’t moldy or watery. My receipts offer a little window into my consumption and allude to the joys and disappointments of winter grocery shopping in Alaska.

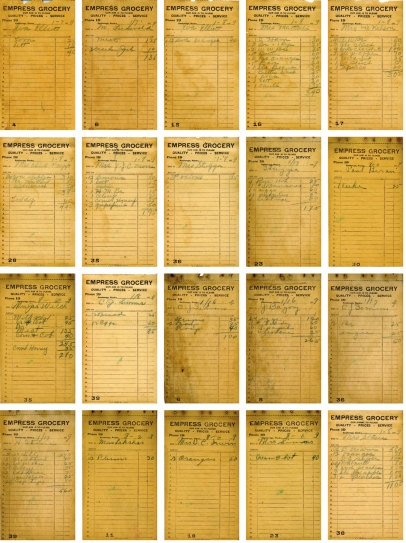

A collection of receipts from Empress Grocery of Anchorage kept from four days in January and two days in August 1929 provide a glimpse into the city’s shopping experience when the population hovered at a little over 2,700. These dozens of receipts were found by John McCool in a crawl space in the Lathrop Building prior to its demolition and donated to the Atwood Resource Center. Each receipt has a date, the customer name, their purchases, and sometimes a city or address. Today, these aging carbon copies feel like archival treasure— handwritten slips that open up stories about day-to-day life.

Not many records exist about Empress Grocery itself. The opening date of the store is unclear, though a court case involving the sale of the business suggests it was open around 1924. Archived phone books give the address of the shop as 803 4th Avenue until closure sometime between 1944 and 1949.

Empress was one of a number of groceries in the city. The early 20th century marked a new era for the food consumer in America. The word “grocery,” in the sense of meaning a store where a grocer’s goods are sold, had only entered the English lexicon a century prior. But, within those 100 years, dramatic changes occurred in food production and consumption. More and more consumers were exchanging the labor of growing the food they put on the table with the expense of buying it. The household grocery shopper of the day, likely female, needed to know how to efficiently buy the best and cheapest tomato, rather than how to grow that tomato. While still a territory, Alaska followed the national trend, though with some lag. Self-service groceries, where customers (rather than a grocer) could select items themselves, began in the United States in 1916 with what would become the chain, Piggly Wiggly. The first self-service grocery opened in Anchorage later, in 1929, the same year as these receipts, just a few blocks away from Empress. That grocery, Lucky’s Self-Service, had the words “in God we trust, all others pay cash” painted on its windows.

While we know little about Empress Grocery, sifting through the 130 or so receipts reveals possible stories about their customers. The scrawled handwriting of the grocer and the abbreviations of both items and names of buyers on the receipts require some guesswork, but the tastes of specific patrons are captured on these slips of paper.

C.J. Simms purchased bread and eggs on January 8th and then was back on the 16th for grapes, soup, and an indecipherable item. Simms was back again on the 17th for bread and sugar. The grapes, though the quantity is unknown, cost 35 cents, an equivalency of just over $5 today. Then a Mrs. Simms, perhaps the same Simms of January, returned on August 8th for a bottle of cream.

I cannot help but wonder a bit about her frequent shopping. I myself love grocery shopping, and I will sometimes treat myself to wandering the aisles after a long, dark winter day. There on those aisles, I find mundane but satisfying pleasure in selecting something bright and nourishing. The volatility of winter shopping only adds to the pleasure of finding something special and ripe, like a bunch of round, tart grapes to bring home unexpectedly, or a dozen small oranges.

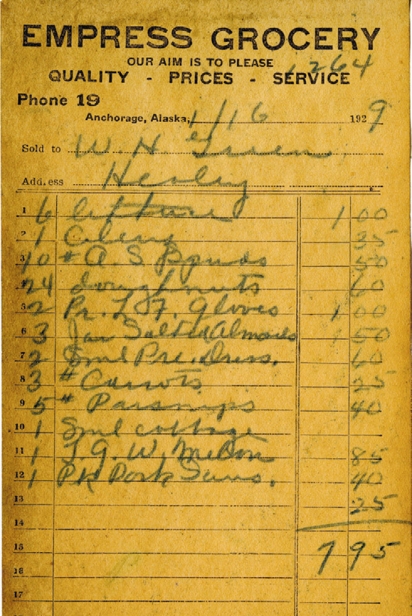

Most shoppers only purchase relatively few items, but W.H. Greene of Healy has one of the longest receipts. He stocked up with $7.95 of items, nearly $120 worth in today’s dollars. He collected staples—ten pounds of potatoes, six lettuces, a small cabbage, a pack of pork jaws, three pounds of carrots and five of parsnips, and a couple pairs of gloves. And, he picked up some treats—24 doughnuts and a jar of salted almonds. Some research reveals that Greene (spelled Green on the receipt), was the railroad station agent in Healy, where he owned Mayflower claims and where some quantity of the mineral bornite was found. I wonder just whom those 24 doughnuts might have been for—fellow rail workers? As a worker on the Alaska Railroad recently completed in 1923, Greene must have had easier access to goods in Anchorage.

Stocking up in town for a family or community before heading to a more rural setting is still familiar to many here in Alaska. Whenever I am in a rush, I always seem to find myself in line behind someone buying a thousand dollars’ worth of groceries and loading each item carefully into totes. Most Americans go to the grocery store one and a half times a week, buying about ten items, and spending about $140 on food. Rural living demands bulk purchasing when residents are in town and have access and choice.

While most of the patrons are anonymous, some of the receipts document the purchases of more prominent characters in Alaska’s history. There is a receipt from the Bagoys of the longstanding Anchorage flower shop for two dozen eggs, a pound of toddy (likely bulk coffee or tea), toilet paper, and Wheatena, a high-fiber wheat cereal.

Then, there is a set of receipts bearing the name Staser. These receipts may belong to Harry Staser, who first came to Alaska in 1909. He arrived as a determined prospector. When just 18 years old, he’d travelled all the way to the Klondike from Indiana. By 1929, the year of these receipts, he was Deputy U.S. Marshal for Anchorage, a post he held from 1923–1933 after meat hunting for mining crews, serving a stint in the Army, working as a mining engineer, and serving as a Republican representative in the territorial legislature. He had married Barbara Francetta De Pencier, whom he had met in Fairbanks on his second trip to Alaska from 1913–1914. The couple moved to Anchorage in 1919, where Barbara made her name, at least in part, as a territorial women’s singles and doubles tennis champion. Both Barbara and Harry had tragic ends. Barbara was in a car accident in 1935, which left her paralyzed from the chest down until her death in 1952. Harry died of a heart attack in 1940 following a hard climb to a mine he had purchased.

The receipts hint at life outside these recorded events for the Stasers. Mrs. Staser purchased cream, a dozen oranges, sugar, walnuts, apples, and canned peaches as well as fresh peaches on January 8th. Could this have been a partial ingredient list for a cake or dessert Barbara then concocted in her kitchen? Another receipt attributed to H. Staser from January 17th included two cans of Hills (likely Hills Bros. coffee), starch, bread, celery, lettuce, a jar of mints, and what appeared to be two cans of asparagus tips.

And, what of those asparagus tips? Asparagus of any other variety than canned remains challenging to find in Anchorage today, virtually any time of year. Canned asparagus is notoriously mushy, and I might even say unpalatable, a far cry from its fresh counterpart. What dish featuring canned asparagus could have been featured on the Staser table? It seems to me that only in the dark depths of winter would one resort to canned asparagus, especially when fresh lettuce, even the much-maligned head of iceberg lettuce, might fill the vegetable portion of the plate.

The collection of receipts also holds some from summer of the same year—August 2nd and 6th. In my Alaska summers, I have learned to grow and wild harvest some of my food. I grocery shop mostly at the farmers markets, buying from local farmers huge vegetables that last many meals. On my occasional trip to the grocery store for cheese or oil or flour, I often find myself distracted in the produce aisle by heaps of stone fruit that look particularly delicious. These tender fruits usually look bruised if they can be found at all other times of year, so I always manage to end up with bags full of fruits and no plan of how to use such a quantity.

Looking at the receipts from Empress from August, I can only imagine shoppers nearly 100 years ago might have had a similar experience. These receipts tend to be shorter and heavy with produce: cucumber, corn on the cob, honeycomb, oranges (now 15 cents cheaper by the dozen than what was sold to Mrs. Staser seven months before). And, the receipt from Mrs. Lakshas for 12 plums. This is likely the receipt of the daughter of John B. Bagoy and Marie Vlahusic Bagoy—Mary Bagoy Lakshas (1913–2014), who operated the Bagoy floral shop until its sale in 1972.

Receipts are so often ephemeral objects. I rarely keep my grocery receipts, and I avoid having them printed whenever possible. So, perhaps my January trips to Natural Pantry for garbanzo bean flour, kombucha, and Greek yogurt won’t have the same longevity as these documents.

There is good reason to move away from these slips of paper— researchers think receipts consume nearly 10 million trees and produce between 600 million and 1 billion pounds of waste in the U.S. alone each year.

The receipts from Empress Grocery held in the Atwood Resource Center are fragile objects. Browned and brittle, they at first appear mundane—detritus from Anchorage’s history. But, with deeper inspection, the collection becomes an accumulation of poetic objects— each receipt a tiny, lyrical encounter with a person and their purchases. There is something intimate about holding these receipts and imagining what dishes might have come from the ingredients listed. The documents tell familiar, personal stories of desire and longing, of hope and possibility found in the grocery aisles in Alaska.

This piece originally appeared in Issue No. 14, Winter 2019