Alaska's Coffee Culture

The Story of Black Cup

As I step from my car outside the Black Cup roastery, everything about the lightly falling snow and soft, blue-gray light of this winter morning says “coffee time.” In the muted daylight of deep winter in Anchorage — and with my visible breath and the sharp cold on my fingertips — I’m reminded that if coffee didn’t already exist, Alaskans would have somehow needed to invent it.

We obviously don’t dipnet for coffee beans on the Kenai each summer. And I don’t disappear into the Chugach mountains and spend an afternoon harvesting a couple buckets of coffee beans to sustain me through the winter. However, is there any single item that I take for granted more than my daily cup of joe?

Lucky for me, Doug Griffin — head roaster and green buyer for Black Cup, my favorite Anchorage coffee roaster — would love to help me correct this oversight, and in the process deepen my appreciation and knowledge of coffee.

For the record, Doug strikes me as someone employed in the best imaginable way: he’s the rare individual who is enlivened, not burdened, by the demands of his craft. When asked, for instance, to clarify his job title (“What’s a green buyer?”) he eschews formalities and defers to artistry: “I think our coffees dictate to us how they’re supposed to be roasted,” he begins, which already sounds like a more delightful job description than anything I’ve ever spotted on Craigslist. “So, my job,” he continues, “involves finding each coffee’s sweet spot — and that’s a lot of fun.”

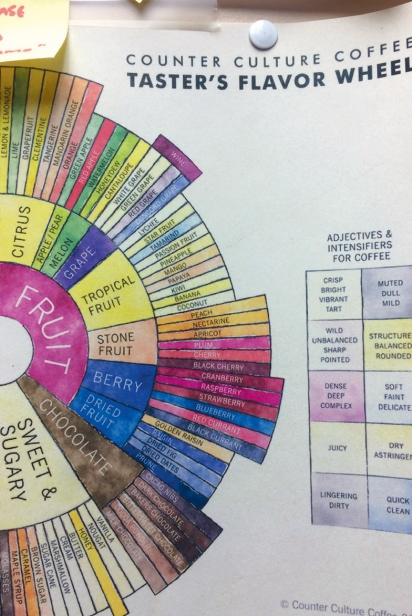

The morning I arrive for rapid immersion in all things Black Cup, Doug is wrapping up a meeting with general manager, Jared Mokli. I tune out their conversation and study the posters and pictures decorating the walls. Black Cup’s roastery could double as a small museum of both coffee and history of Alaska. Illustrations detail the chemical processes at work during roasting, harvest schedules, maps of regions known for their beans, and a “flavor wheel” breaking down the tastes of different varieties. But it’s the memorabilia from Anchorage’s premier specialty coffee company, Café Del Mundo, that most commands my attention.

Alaska’s coffee pioneer, Perry Merkel, launched the Café Del Mundo chain in 1975. When Merkel retired in 2011 he sold his business to Black Cup’s parent company, Kaladi Brothers, and Black Cup moved into the old roastery digs. CDM’s well-loved Benson café location was also given a facelift, providing Black Cup with a fresh environment in which to craft and serve, as per their slogan, “extraordinary coffee best served black.” The Benson location always felt to me like the North Star of CDM cafes, while the others always struck me as satellites. It always felt like CDM’s home base and I think others would concur.

“We’re the only roaster in town pitching black coffee to our customers,” Doug explains, after Mokli leaves, “but we’re doing that by roasting superior coffees that hopefully challenge how we typically think about black coffee.”

To me it seems an unenviable task: even the mention of black coffee conjures images of graduate school all-nighters fueled by gut-scorching French roasts and espressos. However, Black Cup’s lighter roasting process is key to the company’s coffee alchemy. They result in a “cleaner” product than we commonly associate with black coffee, bringing out flavors in the beans that competitors frequently roast out of their products. I, for one, am a convert.

“Still,” Doug admits, “I know it’s a little bit of a jump to our coffees from other more traditional coffees in town.” He recalls, in good humor, occasions that customers have complained about Black Cup’s unconventional characteristics. “Some people describe our coffee as fruity,” Doug chuckles. It’s not the first word I’d use to describe my experience of Black Cup. Wine can be fruity, sure – definitely – but coffee? “We find a lot of floral notes, too. Berries. And now and then we hear it’s ‘earthy,’ too.”

We proceed through the front offices and into the warehouse, where rap music blares from a radio in the far back and competes with what sounds like a roaring freight train in a wind tunnel. He credits the radio volume to the staff, and the rest to the roaster doing its job.

Not minding the noise, I’m soon standing in coffee-lover’s heaven: the whole warehouse smells like that single moment when you cut open a new bag of beans in your kitchen and get the first full scent of all that robust goodness stored inside.

Stacks of burlap sacks full of green coffee beans rest on shelves and are piled on pallets across the floor, stamped with logos from exotic locations far, far away — most from Africa and South America. It’s staggering to try and comprehend that each sack represents the tireless work of farmers and workers in a specific coffee region. The fact that the product even exists, then arrives here, and then finds its way to my neighborhood café in Anchorage, Alaska, speaks to a journey and a process that I need to more often properly appreciate.

“As much as I love this work,” Doug explains, “it’s one business that comes with all kinds of significant risks built into it … and a lot of those are in play before we’ve even seen the coffee.” For example, how, in Anchorage, Alaska, do you plan around or compensate for a season’s poor harvest in, say, Rwanda or Colombia? And then, even following a given year’s successful crop, what if it gets damaged in transit?

“Some of our coffees reach the states two or three months after harvesting,” Doug explains, citing a coffee Black Cup purchased from East Africa that spent three months on a barge journeying here. “Coffee beans have a lot of oils and are very absorbent, so they’re always vulnerable to any chemicals or toxins they encounter on their journey. It can get a little stressful imagining a high-quality coffee sitting on a dock somewhere, absorbing whatever fumes or chemicals are drifting around in that space.”

Doug leads me around the corner, revealing the hulking Probat G90, the German drum style roaster responsible for the majority of our morning’s sound effects. This is the beast through which all of Black Cup’s coffees are transformed from green beans into the brown, flavor-packed varieties that will eventually find their way to the café.

The roaster on duty today, young and upbeat Damen — who is also an award-winning barista at the midtown café — is all motion as he briskly works the machine and studies the outcome of his last roast. Soon he and Doug begin pointing out the different features of the Probat in the same way friends might explain the superior details of their cars. When they’re done, I understand that the roaster’s adjustable controls and distinguishing components help regulate heat application, airflow, and custom roast profiles as desired. Beyond that, I’m willing to believe the rest is credited to magic.

On our way back through the warehouse, Doug throws me a curve ball.

“Did your parents drink coffee from those big cans?”

“You mean like Maxwell House?” I ask.

“Yeah. Folgers, Yuban. All that stuff ...”

I actually can’t recall how my parents used to brew their coffee, or what coffee they preferred. I do, however, associate those big Maxwell House and Hills Brothers cans — mouths wide as the Alaska pipeline — with the thin, hot drink my grandmother would serve in little china cups with dessert at family gatherings.

“The consistency of that stuff seemed more like a coffee-flavored tea than what I consider coffee now,” I remember, snickering. Doug laughs in solidarity.

“Right — and yet that was specific to that generation’s experience of coffee. In the coffee world we now refer to that period as the ‘First Wave’ of coffee.”

Doug explains that the specialty coffees Perry Merkel began roasting and crafting from his shed in his backyard in Anchorage in the 1970s could represent the transition into what’s now recognized as coffee’s “Second Wave.” In the larger coffee world, however, that period is marked by the arrival and then rapid rise of the Starbucks chain, the burgeoning local café scenes in cities across the country, and the notable emphasis on quality and fairly traded coffees and espressos. Look no further than Anchorage’s own Kaladi Brothers chain and their popular espresso drinks for another successful Alaska representative of the Second Wave in coffee’s recent business history.

Now, Doug continues — amusingly conscious of how indulgent it might seem to a layman coffee drinker — we are deep into coffee’s Third Wave. “Everything now is about the story of the coffee,” he says. “It’s all about transparency with the farms we work with, and showcasing the story of the region and the coffees we’re sourcing.” For Black Cup, this comes with the added emphasis on black coffee.

When Merkel sold CDM to Kaladi, Doug — then a film school graduate roasting for the company while funding a documentary project — saw an opportunity to take specialty coffee to the next level in a way that complimented his passion for both craft and storytelling. Sure enough, a quick scan through Black Cup’s social media reveals, in addition to a stream of the café’s baristas brandishing their skills, pictures and captions detailing the bios of farmers with whom they do business, along with close-ups and descriptions of specific coffee plants, and varieties of freshly sourced beans from much warmer climates than Alaska.

I’m due at another appointment soon and as I prepare to leave Doug reminds me to join the crew tomorrow for Black Cup’s weekly cupping and tasting session.

Back in my struggling, frosted Subaru, I turn the defroster on and wait for the engine to warm. The sun is out now, but I’m rubbing my hands together and shivering in my seat when I realize that I drifted through the entire roastery tour on only a contact high of coffee scents and coffee talk. Meanwhile, I still haven’t consumed any coffee today. I look at the clock and wonder if I have time for a quick coffee detour before my meeting across town.

Silly question. Of course I do.