Congratulations to Calypso Farm & Ecology Center's Class of 2017

(Part 2 of 4)

When the new crop of farmer hopefuls arrived at Calypso Farm in Ester last April, there was no soil in sight. The farm’s acreage remained buried under thick snow. “Everything was dead,” says California native Holly Brookings. Interior Alaska doesn’t give up on winter easily.

The Farmer Training Program would start May 1, but for several weeks more, the students would just have to imagine climbing up and down the soil terraces, planting rows of flowers, vegetables, herbs, and, soon enough, crouching down to thin and weed the plants to encourage abundance.

Even so, the tail end of an Alaska winter provides fine first lessons. You have to keep your land under close watch. Glossy magazine farm life is not real farm life. This life, this work, takes persistence, sweat, smarts, and patience — and a damn lot of each. If the students didn’t know that before their first class started, they would by the end of day one.

“My biggest concern for these farmers is the economic viability of their business,” says Susan Willsrud, co-founder of Calypso and the Farmer Training Program. She and her husband, Tom Zimmer, want to shift students’ thinking away from the accepted — but, they believe, ridiculous — paradigms of small farming: that farming can’t be a money maker or they should just farm until the money is gone. Adds Willsrud: “You also shouldn’t be doing this to be impoverished.”

It’s June now, a Wednesday. Snow wouldn’t stand a chance under this early season heat wave. Now the farm is all life, the terraced rows already playing host to some of the hundreds of varieties of vegetables that will make their way to the local farmers market and CSA boxes. Camp counselors in their late teens and early 20s welcome a crowd of five- six- and seven-year-olds for another Calypso program, the weeklong Farm Camp. Goats bleat. The sheep do their thing. The two pigs? They’re stretched out in the shadiest part of the pen, lazing away and bulking up.

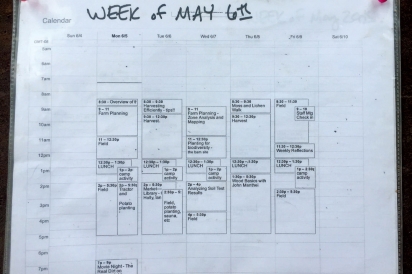

The Farmer Training Program students are out of the sun for now in the fiber studio, a catch-all space for classes, wool spinning, late night studying or whatever role it needs to take on. One wall plays host to shelves that spill over with wool roving in colors ranging from the earthy off-white of undyed wool to supersonic eyeball-blasting brights. But today, like every Monday and Wednesday morning throughout the program, Farm Planning class is in session.

Sitting in mismatched chairs around the kind of sturdy plastic folding tables that Costco sells, the students — including two locals who signed on just for the farm planning lessons — listen as Willsrud talks about branding their businesses. Some students already have family land to build their plan around (or family members helping scout land to buy back home), while others play the farm version of fantasy football, using real-world information about property and prices to build out a detailed farm plan.

Willsrud explains branding by mixing success tales of small farms and large international companies together, showcasing anything that will help her students focus in on what it means to build a brand. The next step will be to gather images for a mood board (either on Pinterest or on poster board). The mood board process, sounding a drop more like something out of Oprah than an ag class, will give each person the chance to collect images that showcase what they want for their farm’s look and feel.

“Oh my gosh, this is super difficult,” says Carrie Bookheimer, a Pittsburgh native who has been working on an organic farm in Pennsylvania since finishing college the previous year. “I have some adjectives here,” she says. “Like homey, whole, thoughtful, fresh, passionate. I don’t have colors in mind yet. I don’t think it’s clear because I don’t have a name I’ve decided on.”

But Willsrud doesn’t allow her students to fold in on themselves when the business side frightens them. “It can keep evolving,” she says. “That’s the whole idea. This is the brainstormy phase.”

Over time, some of these images will drop away, others will move forward and coalesce. They will finalize names for their farms and be able to see their business, their future. They will make fantasy football players look like amateurs when it comes to building a fully-realized world.

“It’s my dream on a piece of paper,” says Holly Brookings. The rest of the group laughs. It’s an amiable bunch and, over the past month of living, eating, and working together, they’ve taken on the ease of a group that has known each other much longer.

“It will be your dream on a piece of paper, but in order to make it real you’ve got to accept the fact that you won’t be able to make it perfect,” says Willsrud. A few scrunched faces make it clear that the perfectionists in the group are learning a few extra lessons about farming.

Like MBA students, each farmer-in-training will end the program with a complete business plan. Groans go out from the group when Willsrud reminds them that there’s public speaking ahead: each student will present his or her plan to a group of local farmers and other business people who will poke holes, ask tough questions, and make sure the farms — real or imagined — don’t sink under the weight of their farmers’ ambitions.

Visions of mood boards dancing in their heads, the planning class comes to an end. Their next classroom: the earth. The students shepherd flower starts from the open flatbed of a truck to a small hand-built pond for soaking. Several of the camp kids kneel on the side watching the action, helping when allowed. Both students and campers carry the flower and ivy starts over a hill to where they’ll be planted. Willsrud gives a basic lesson on what should go where, leaving the students to do most of the planning and figuring themselves.

When anybody hunches a bit too much or looks like they may end the day feeling more like a twisted pretzel than a strong human, Willsrud reminds them to work with their bodies instead of against them, reinforcing the best ways to bend in order to keep their work from upending their health. Balance, always.

After planting the group breaks for lunch in one of the property’s yurts — a building that swirls with staffers, family members, campers, and, in tanks, some frogs captured by campers earlier in the day. The students look mildly spent, but still enthusiastic. The heat keeps beads of sweat on their faces but they don’t let it stop them — with a woodworking shop taught by John Manthei, one of the founders of The Folk School in Fairbanks, and a soil analysis class taught by Tom Zimmer still ahead, there’s no time to stop. There’s always something else to do on the farm.