Alaska's Storied Reindeer Industry Finds New Ways to Survive

When manager Lauren Waite opened the gate at Reindeer Farm in Palmer, two things struck me about the herd of lounging reindeer I saw: their size and their friendliness.

The reindeer remind me of caribou I’m used to seeing on the side of the road or scampering over tundra. And they should; they’re the same species. But the reindeers’ legs look stunted, their faces cuter, and their mannerisms more dog-like than wild.

“This is Spike,” said Waite, gesturing toward a wide-eyed bull who kept nuzzling my hand in search of treats and affection. Two circles scarred the top of his head, remnants of recently shed antlers. “He’s special because he’s actually a twin. They’re not common at all. We bottle raised him.” Waite rolled out names as we meandered through the herd: Spike’s sister Spicy, and Peter Pan, Clifford, Jean Valjean. This is the farm’s pet herd.

“The way that these guys are, I mean, they are all over you. They come up, they chew on you, they kiss you. They love people too,” she said. “They just have something special about them, and it’s something that no other animal has… They just have that reindeer magic.”

On a cold day in February, the 160-acre farm was quiet, aside from a whipping wind and the sporadic gobble of turkeys, but in the summer, this place crawls with visitors. Tourists are eager to feed reindeer at a latitude that many associate with Santa Claus. Agritourism dominates Reindeer Farm’s business model, and Waite said visitation keeps growing. Five years ago, they started offering winter tours to meet increased demand.

Their model is a far cry from what Waite’s grandfather intended when he converted what was originally a Matanuska Colony dairy farm into a reindeer haven in 1987. He bought 20 reindeer from Tuktoyaktuk, Canada, to start a meat operation. The business now has around 100.

Then people started showing up at the farm, curious to see and feed the reindeer. “We thought, if the people were going to show up anyway, we might as well start doing tours for them,” Waite said. When her mother took over in 2010, the family decided to shift focus almost entirely to tourism. This is because reindeer are expensive—a live reindeer can fetch $10,000 or more thanks in part to their value to tourists—and part of the family.

“We love them. We know all their names; we know all their mommies, so we would love for them to live long lives.” Waite said most visitors are offended at the thought of eating reindeer.

Reindeer Farm does have a second, less friendly herd of reindeer that they sell to other farms for a premium or to processing facilities like Alaska Sausage and Seafood Co., and they also run a reindeer dog food truck in the summer. But those endeavors are only a small fraction of their business.

Waite’s family isn’t alone. Reindeer farmer George Aguiar said the handful of reindeer farmers on the road system are increasingly finding tourism more profitable than meat production.

“People can have a business that can survive and continue to bring money in and still have their animals. They can do quite well for themselves with only a few,” he said.

Aguiar owns Archipelago Farms in Fairbanks, where he raises between 50 and 70 reindeer at a time. He supplements the farm’s income with tourism, renting reindeer out for events, but his real passion is growing a sustainable meat industry in a state far from so many of its food sources.

“I constantly try to keep my foot in the door of the meat thing. I think it’s a really important tool as a way to keep your herd healthy,” Aguiar said. “This tourism thing, I don’t think it will be gone tomorrow, but it can change really quickly. I think it’s really important to have multiple outlets, in case any of those outlets change, in order to survive.”

Challenges like the cost of feed, lack of specialized equipment and veterinary care, limited land on the road system for grazing, and the fact that they can only be slaughtered at certain times of the year, make meat production difficult. But these hardy animals do thrive in Northern climates, making them better suited to Alaska than many other livestock. And being on the road system means Aguiar has access to a USDA-approved slaughter facility, so Archipelago can sell some of their meat to butchers like Iced Aged Charcuterie, which turn it into products like salami. People are hungry for reindeer.

“We can sell reindeer meat all day long. I mean everybody wants this stuff,” Aguiar said. “It’s a high quality, high protein, low fat, high mineral product—fine fiber, so it’s very tender, and it demands a high price on the market if available. It’s just really difficult to find.”

Fenced herd farmers like Aguiar and Waite represent a small segment of Alaska’s reindeer industry. Herds of thousands still thrive in Western Alaska where they were first introduced, and there, they’re adapting to a whole different set of challenges.

A Wild Experiment

For most of the year, around 2,500 reindeer roam free on the tundra of Nunivak Island in Southwestern Alaska, feeding on lichen and native plants. But once there’s enough snow, their herders venture out on snow machines to round some up for slaughter.

“We call them Arctic cowboys,” said Terry Don, manager of Nuniwarmiut Reindeer and Seafood Products, which processes and distributes the meat. The herd is owned by the Nuniwarmiut people, and managing it means battling high winds, low temperatures, and broken snow machine parts.

“People don’t realize how much work is involved in managing reindeer,” Don said. “Many longtime reindeer herders are getting older. The older you get, the harder it gets on your body, bouncing on the tundra for eight to ten hours at a time.”

Don, who grew up on Nunivak Island and also leads the local village corporation, is working with others to attract the next generation of reindeer herders through educational programming that connects elders to young people. He’s hoping to carry on a century-old tradition in an area where imported food costs are high, and supply chain disruptions are common. He’s also working to smooth out logistical challenges, so the business can export beyond the island and the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta to the rest of Alaska. Like Aguiar, the company can’t keep up with demand.

“It costs an arm and leg to fly everything out of or in to the island,” Don said. “If we’re able to provide a reliable, sustainable protein source here in Alaska without having to import such a long way, that would be great.”

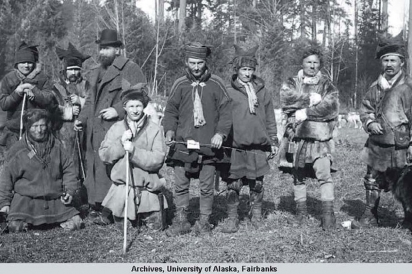

The dream of reindeer meat tackling food security in Alaska extends back to the late 19th century, when Sheldon Jackson, Alaska General Agent of Education and Christian missionary, brought reindeer to Western Alaska from Russia’s Chukchi Peninsula and later Scandinavia, where herders domesticated caribou thousands of years ago. The government-backed program aimed to address food shortages—particularly among Alaska Native communities—following the collapse of the whaling industry, plummeting marine mammal populations, and changing caribou migration patterns. The project even brought Sami reindeer herders from Scandinavia to teach reindeer herding in Alaska.

“What a wild journey, I mean trying to get human beings and reindeer across the Atlantic and the entire United States, and then to Alaska,” said historian and author Bathsheba Demuth, who’s written about the reindeer industry worldwide.

As with other agricultural experiments in Alaska—like the Delta Barley Project and the Matanuska Colony Project—government officials and entrepreneurs imagined a lasting industry large enough to export.

“They had these really grandiose thoughts about, you know, we’re going to feed the country, and there’re going to be 3 million reindeer on the American tundra,” Demuth said. “[The missionaries] came from the Great Plains, and they showed up in Northwestern Alaska and there were no amber waves of green. And so the reindeer were supposed to kind of be the substitute for that.”

According to a University of Alaska Fairbanks history of the reindeer industry, it peaked at over 600,000 in the early 1930s, their owners mostly mission schools and non-Native herders. For a short time, Alaskans did even export meat to the Lower 48. To preserve the original intention of the project, Congress passed the Reindeer Industry Act of 1937, restricting the herding of Alaska’s reindeer to Alaska Natives, a law that still exists today. But by then, Demuth said, The Great Depression and the beef industry nudged a decline that never bounced back. (Farmers like Aguiar and Waite bought their stocks in Canada; Waite’s grandfather fought a long legal battle to get any non-Native ownership of reindeer in Alaska allowed.)

Good data on Alaska’s reindeer industry are hard to come by, especially with the recent closure of the UAF’s Reindeer Research Program and a change in leadership at Kawerak’s Reindeer Herders Association. Old estimates of around 15,000 reindeer in Western Alaska—mostly concentrated on the Seward Peninsula—are likely on the high end. Only a few hundred live on the road system. In some places, returning wild caribou herds have taken in, or “stolen,” domestic reindeer. In others, climate change-induced erosion and flooding have washed away corrals. Other perennial industry challenges abound, like predators; shipping logistics; and accessing veterinary care, inspectors, and slaughtering facilities.

“If you read the package on a [commercial] reindeer sausage, it says it contains less than two percent reindeer meat,” said Professor Jackie Hrabok from UAF’s High Latitude Management Program, which trains reindeer farmers and provides support for the industry. “It’s that way because the number of reindeer that are USDA-inspected in the state of Alaska ranges from about two to 300 animals. So how much sausage can you make out of only 300 animals?”

Right now, a lot of reindeer meat is sold in-state under field slaughter regulations, which allow meat to go uninspected, but require the herder to keep the carcasses frozen until they’re sold directly to the consumer. That poses all sorts of challenges in a changing climate and can negatively impact quality and access to different markets. It also doesn’t allow for the production of sausage.

At first glance, the meat sector of the industry may look like it’s dwindling, just a shadow of its original intention. But Hrabok would argue otherwise. The High Latitude Management Program trains new students every year, taking them out on the tundra to learn from elders about the wild plants the reindeer eat. Her program recently received federal grant funding through the Farm Bill to address a variety of the industry’s needs, including creating a mobile slaughtering unit where U.S. Department of Agriculture-certified processing can occur. Don’s company is in the process of permitting a similar facility.

“I think it will grow, as long as all of us different parties work together and share the information, and as long as we keep it open to really trying to serve,” Hrabok said about the industry. “Like what’s the main goal of doing this? If it’s only about money, it’s not going to work because then you’re not thinking about everyone… You know, you’re planning for the next generation.”

Both Hrabok and Don see the continuation of reindeer herding as an important step in connecting young people with traditional foods, and they both see new opportunities for the industry, like using hides and antlers to make crafts to sell to tourists. Don has even visited Texas ranches and Scandinavian reindeer herds searching for new ways to survive and thrive.

The two are eager to see the reindeer industry realize its full potential, even if it looks a lot more Alaskan than its founders may have envisioned.

This story originally appeared in Issue No. 28, Summer 2023