Complete, Eaten, and Over; Summer Distractions

I try to write about food in summer and get distracted by food: by the gathering, growing, or eating of it. Food is everywhere except my kitchen in summer, when I rarely cook meals at home, relying on what can be easily thawed and heated or pulled from the ground and eaten raw, or alternately, made by someone else and paid for, a seasonal luxury in the tourism economy of the Denali Park area. Even at work in a bakery, days go by when I eat nothing but bread scraps and lettuce until my protein cravings overwhelm me and I head to the nearest bar, which is fortunately owned by award-winning chef Laura Cole, and serves fresh oysters that I eat with a reverence like prayer. I bring a notebook, pretending I’ll get something written. A friend sits down at the next stool with a newspaper she pretends she’ll read, and says she’s popped her summer restaurant cherry and now can’t stop going out to eat. We shake our heads at the confused and delicious mess of the season.

Restaurants, like songbirds or wildflowers, are a brief and flamboyant occurrence in the Denali Borough, and if you’re busy with other things it’s possible not to notice them at all. One day, after planning to write but instead driving an hour north to look for morels where last year’s wildfire swept through the woods, a friend and I stop at a brand-new tourist bar for drinks, partly because we’re curious and partly because we want a drink, but mostly for the shallow pleasure of wearing soot-streaked jeans in a sanitized brand-new tourist bar.

My friend asks the bartender why the menu lists an ice axe, crampons, and a dogsled, and he gestures behind him to what seems to be an actual display of these items, and says, with a faraway look in his eye, “And I guess we’re gonna get a dogsled soon.” My friend and I consider the plausibility of someone—not us—getting drunk and buying an ice axe. We talk about morels, how we will dry and freeze and eat them, though the journey barely registered as food-related while we wandered the scorched woods from mushroom to mushroom standing stark in the bright sunlight, trying to find patterns: are they more likely to grow from the trees’ burnt roots? Or on the southern slope of a blackened slough? Had we followed in the exact footprints of our neighbor Chris, who had picked gallons three days earlier and left the topless stems we’d found? It’s a shorter distance from the burnt forest to a meal than from a packaged ice axe on a shelf, and we pay our bill and head home.

But the greenhouse is by far the place I spend the most time not writing in summer. It’s avoidance disguised as necessary labor. I spend hours watering, thinning, pulling chickweed from between pea plants, comparing this year’s growth to last: beets ahead of schedule. Broccoli behind.

In February of 2015, my friends' son Eider was born the day after I planted broccoli seeds. It wasn’t intentional, but two weeks later, when the baby visited the house for the first time, I realized how my planting dates lined up with his birth. His mom Sarah and I started what became a summer-long ritual of photographing Eider next to the broccoli plant, and the hashtag “#eiderandthebroccoli” was born. Eider became a small town internet celebrity as he and the broccoli grew together.

He’s a small baby, and the plant dwarfed him by Solstice, when the photo shows Eider gumming a thick stalk, held upright in the dirt by his mom’s hands, leaves overhead like umbrellas. By this time he recognized that a visit to Aunty Erica’s meant being plopped in the dirt surrounded by green, a black rectangular phone waved in his face as we took pictures.

Solid food was still an abstraction to Eider when I harvested the broccoli in mid-July, but I blanched and froze most of that plant till his teeth and digestive system caught up.

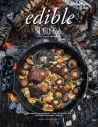

Rebecca Solnit writes that “Cooking…seems so pleasurable because it is the opposite of writing; it engages all the senses; it’s immediate and unreproducible and then it’s complete and eaten and over.” She could be describing summer, too: the fast-paced rituals of gathering, growing, putting away.

By October, Eider had learned to move bites of salmon and vegetables from his parents’ plates and to his mouth, nose, or ears, and we had settled back into winter mode: meals that took longer to make, and longer to eat. Our two households gathered to document Eider’s consumption of the plant that emerged into the world when he did. We took great joy in his eating, and in feeding him what we’d grown.