Crevasse Candy

All We’re Cracked Up to Be

Food always tastes better on top of a glacier. Humble turkey wraps and sugar-free protein bars are luxurious when washed down with heavy gulps of pure glacier water and vibrant valley views. My colleagues and I racked up hundreds of these lunches on the surface of Seward’s vanishing Exit Glacier—clipped into an ice anchor that could hold the equivalent of 5,000 pints of ice cream. Fueling ourselves with bites between climbs, we hung over the edge of eight-story-deep cracks in the ice, lowering lucky visitors into the blue belly of our favorite glacier to help them build a relationship with our rapidly changing planet.

On the same menu, drinks transform when chilled with hunks of glacier ice. As fluffy snow compresses into glacier ice, some 20 percent of air becomes trapped in tiny bubbles within. The sound of my beverage popping as those air bubbles released once reminded me of Pop Rocks crackling on blue childhood tongues.

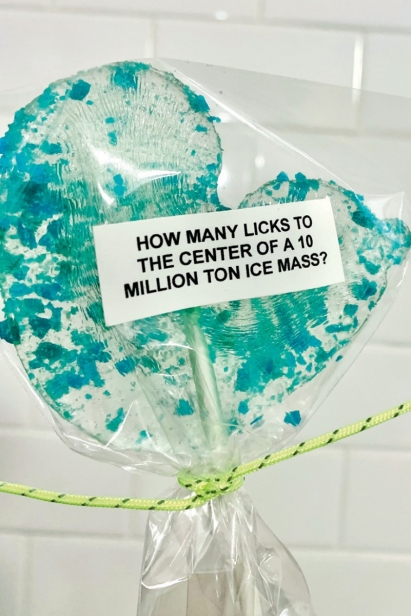

Climbing gear unpacked and back in my kitchen, I boiled sugar with a bit of water from Exit Glacier. Cooking that mixture to 300° F—six times that of Seward’s average summer temperature, which is already threatening Exit Glacier’s frozen existence—allowed me to manipulate the substance to mimic crevasse formation. I removed it from the heat and added Champagne extract to carry the through-line of playful effervescence, then poured three-inch circles onto a greased stainless-steel table.

Like water in a river, ice in the middle of a glacier often flows faster than ice on the margins, where it’s slowed by friction from adjacent landforms. This disparity in speed ruptures the surface of the ice. As my hot sugar mixture slowly cooled, I pressed my thumb against the top and pushed it toward the sweet center while holding the edges in place with my other hand. Immediately, sugar crevasses tore their way across the glaciated lollipop. Working quickly to finish, my friend and fellow pastry chef Chelsea Burgess suggested heating the back of the lollipop to soften the sugar before pressing it into tingling blue raspberry Pop Rocks—a culinary soundscape that immediately transported me back onto the ice. A few months later, we handcrafted hundreds of these lollipops and shipped 205 boxes of glacier desserts to science-art enthusiasts across the United States.

Crevasses open as glacial ice oozes its way down a valley like thick honey. As ice is both pulled from below by gravity and pushed from above under the weight of newly accumulating snow, it becomes stressed by so much movement. Though all are naturally occurring processes, accumulation, movement, and obstacles all stress our glaciers to their breaking point.

Glaciers ground me to Alaska’s environment; they also drive me to become better informed and engaged in our culinary landscape. It’s all too easy to forget glaciers’ roles in Alaska’s food story, even though our frozen landscapes drive everything from vigorous coastal ecosystems to the Mat-Su Valley’s agricultural abundance.

Glacial crevasses are relatively short-lived. As a glacier’s stress is reduced—say, when there are fewer rocky obstacles for the mass of ice to maneuver over—crevasses compress back together, recreating safer surfaces for travel.

Many visitors to Alaska hold the preconceived notion that glaciers are frozen wastelands—inhospitable to all but the most experienced human mountaineers. It’s unbelievably exciting to reintroduce these frigid masses as key to life in Alaska. Glaciers grind up bedrock, sending mineral-rich silt into our oceans and rivers. This silt encourages massive phytoplankton blooms that support our dynamic salmon population. Glaciers also help feed and cool our streams in the peak of summer, stabilizing northern sea life’s preferred climate. Silt deposits where rivers pour into the sea provide the perfect habitat for mussels and urchins—the ultimate buffet for a productive sea otter community. Small krill feed on the same phytoplankton blooms as our salmon, and form the backbone of giant whales’ feasts. Even ignoring hydrological systems, humans benefit immensely from bountiful hunting in the forests and cleared lands which are left behind in the footprint of retreating glaciers—with dozens of species of edible berries and plants to round out a filling meal. (According to the Alaska Food Policy Council’s most recent food security report, in 2014, the value of food our state hunted and foraged is estimated at $900 million.)

Like glaciers, our movement on this land will sculpt its future—for better or for worse. Glaciers don’t get a say in how fast they move. Glaciers don’t get to choose their impact on an environment. We do. As my mouth electrified with crackling pops and the ripples of sugar crevasses slid across my taste buds, I recommitted myself to telling intentional stories of place through the topography of dessert. As we all move through a rapidly changing (and equally rocky) landscape, I find hope in the possibility of cracking apart our former understandings and allowing a more sustainable final course to fill our minds and stomachs.

Editors’ Note: This is the final part is a series of four stand-alone pieces about glacier science and desserts in all four seasons. Check out Rose’s stories about glacier mice truffles, ice worm gummies, and watermelon snow in our last three issues, in print or online.

First published in Edible Alaska Summer 2024.