Deer Heart

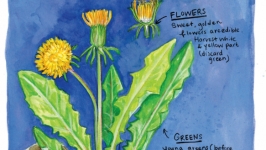

I’ve always associated the plant called deer heart with my times hunting Sitka blacktail deer in Southeast Alaska high country, which is something I’ve done pretty much every August since I was a kid. It’s a small, fragile plant that consists of a single heart-shaped leaf attached to a stem that usually doesn’t grow much higher than six inches. Deer heart grows from sea level, where it’s most tender and nutritious early in the summer, to mountain tops, where it’s best to eat late in the season. Deer follow it and other vegetation up mountains as summer advances. By mid-September, when deer heart is all but dead in the high country, deer descend to lower elevations for better browsing.

Last August, during a hunt, I came upon a deer I’d shot lying on a deer heart-covered bench, with semi-pulverized pieces of the plant in its mouth. There was an ethereal slant to the evening light, the sort that illuminates subtle, hard-to-see details of the landscape. I was surrounded everywhere by deer heart, except where there were cliffs, rockfaces, and the occasional clump of stunted mountain hemlock. I am frequently caught off guard by how something as seemingly simple as shifting light can reveal in an instant how miraculous the world is. I plucked a heart-shaped leaf and stuck it in my mouth. It’s peppery, like arugula, but has an aftertaste that oscillates between good and a little strong. I’d never thought a lot about deer heart, other than using the amount of it browsed as a gauge for where to hunt deer, and to try not to slip on it when it’s raining. I looked from the fields of deer heart to the dead animal, wondering why it’s so easy to become preoccupied with certain things while being blind to so much. I thanked and apologized to the deer, then sliced my knife through the hide along the backbone from the base of the skull to the tail. I cut one side of quarters free, peeled off a backstrap and, before removing a side of ribs, severed the heart and lay it upon its namesake plant.

It was dark by the time I hung my heavy game bags from a branch of a mountain hemlock. During the night I listened as the wind made the tent shudder and bushes crackle. I thought about brown bears. I washed off the deer’s blood the best I could and peed and spat around the tent, but I still smelled “delicious.” Years before, I left a trail camera on a salmon stream that had a high number of bears fishing on it a few miles from where I was hunting. As an experiment, I peed in front of where the camera was pointed to see how animals would react. I returned a few days later and found that most of the images showed bears running away, looking terrified. A young bear even dropped the salmon it was carrying in its rush to get away. One large bear, however, behaved differently. It came during the night and, instead of fleeing, crawled like a cat toward the camera. I imagined that animal crawling toward the tent and thought about becoming meat.

At home, I organized the deer meat in trays divided by roasts, steak, and scraps I’d grind into burger. I trimmed the bones; later, I’d render broth from them. My two young sons—one a toddler and the other three and a half years old—“helped” by sawing on meat with butter knives and dropping pieces of burger meat into the grinder. I sliced a heart thin and doused it with sesame oil and Montreal steak seasoning. When it was done, we snacked as I wrapped meat in freezer paper. Some people do not like the taste or texture of heart. It’s always the first part of the animal I eat, which is in a large part because it does not freeze well. It’s also delicious and, more than that, evocative of much of what I love about life in Southeast Alaska.

Three years prior, my wife and I gave our eldest son his first solid food. We wanted our kids’ first tastes of food to be of something we loved, that came from the streams and forests where we live. First we mashed up blueberries, then we tried coho salmon. It had not gone over well. Not long after, I brought a deer home and fed our son small bits of fried heart. He devoured them.

Once we had a couple of deer, as well as a good supply of salmon in the freezer, it was time to go berry picking. When the next sunny day came, we headed to one of our favorite blueberry patches in the mountains. I carried our toddler in a backpack. As we hiked a trail to a field of deer heart, his brother demanded, and constantly added details to, a story about dragons from his mother. Though it was only the third week of August, most of the plants were showing the first signs of brown. After placing the boys on drier ground where they could play and pick berries, my wife and I set to filling our buckets.

Food gathering, whether hunting or berry picking, is probably the most meditative activity I know. For a while I picked alone, my thoughts quieting as I focused on filling my bucket. Occasionally, the boys would punch or bite each other and scream and cry. Other times they giggled as they wrestled and popped blueberries into each other’s mouth. When I checked on them, they were taking turns smashing blueberries on each other’s heads, both of their smiling faces stained purplish red, sitting amidst deer heart.

The pickings were pretty good and after a couple hours we had a few gallons. I joined the boys and their mother on a small plateau covered in deer heart fringed with bushes heavily laden with blueberries. The light on the mountains had that same ethereal quality, revealing cracks and fissures worn by time in rockfaces and millions of deer hearts surrounding us.

It was hard to walk away from something so good. I placed my younger son in his backpack and, before leaving, searched for a tender looking deer heart. Near where a deer had been browsing, I plucked a leaf and then placed it in my mouth. I slowly chewed, its enigmatic taste engulfing my taste buds, as I followed my wife and older son down the mountain.

Originally published in Issue No. 26, Winter 2022