The Domestic Alchemy of Silver

The chemical symbol for silver is Ag. The abbreviation derives from the Latin argentum, meaning silver. Culturally and scientifically, silver has a kind of alchemical lure. Theories, real and outlandish, about its powers, as well as its relative scarcity and wide commercial application have long made it a valued, desirable substance.

On the day I write this, silver is valued at $737.20 per kilo. But why are we talking about a precious metal in a food journal? Silver is of course associated with setting our tables. No matter what substance we use for our cutlery, we often dub it “silverware” or just “silver,” going back to around 1300 in the English language. The use of silver for utensils and cooking accoutrements in western kitchens has much older origins in ancient Rome. Silver’s oligodynamic and antimicrobial properties, durability, and relatively low reactivity made it ideal for crafting utensils to eat with, such as forks and knives, as opposed to hands. Cutlery gained popularity in western culture in the mid 1700s.

For centuries, cutlery was carried individually as a personal item for dining by those with means. Silver utensils were reserved for the elite, hence the cliché, “born with a silver spoon in your mouth,” to denote being born into privilege. True silverware was out of reach for most households until innovations in industry (which allowed for greater production) and electroplating (which allowed for less silver to be used) made silver sets more accessible. While most table settings today are placed with flatware made of the more inert (less reactive) and affordable stainless steel, silver gleams on white tablecloths in fine restaurants with a traditional atmosphere. And in some households, inherited sets of silver can be found under sinks or in backs of closets, to make rare appearances for special occasions.

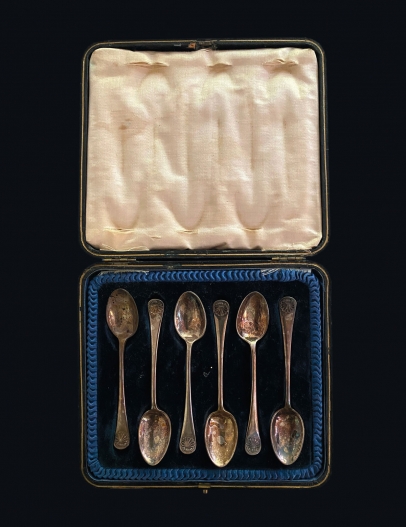

This brings me to a set of tiny silver spoons I keep at hand in my kitchen. Contained in a blue velvet-lined box, the six spoons feel undeniably precious: both valuable and adorable. Just four inches long, the spoons are minuscule, yet have a significant weight when slipped from their soft beds.

They come to me via my mother from my grandmother who was a collector of many souvenirs from travel. Adorned with a scallop pattern, the backs of the spoons bear markings indicating they are made of sterling silver, not plated, and produced in Sheffield, England in the mid-19th century.

For centuries, cutlery was carried individually as a personal item for dining by those with means. Silver utensils were reserved for the elite, hence the cliché, “born with a silver spoon in your mouth,” to denote being born into privilege.

The size of these diminutive utensils classes them as demitasse spoons. Literally, a half (demi) cup (tasse), demitasse service gained popularity in France in the early 19th century. Holding just two or three ounces, a small cup filled with strong coffee was served with accompanying saucer and spoon. The intent of this tiny cup after a meal was to ward off inebriation. Following strict etiquette, demitasse was traditionally served sans cream, milk, or refills. So the mandatory silver spoon for stirring seems a rather performative gesture, though perhaps could be used to dissolve a debatably permissible lump of sugar. The etiquette went so far in the English style of service so that only women received demitasse while men remained in another room to drink brandy.

The petite size and excessive politesse associated with these spoons might make them seem impractical and outdated. But these Lilliputian spoons have a kind of magic, fitting of the alchemical history of the argentum of their making. Despite a bit of tarnish acquired from years of storage, my set of six spoons gleams, shining and bright. In hand, they demand a delicate posture for stirring or eating: thumb and forefinger in a balletic curl. The wee bowls of the spoons encourage taking and savoring small bites.

Often inherited, precious things are tucked away for a more special time. For as long as I remember, my mother set the family table with silver. Even when I was still in a booster chair, I wielded silver butter knives against my hotdogs and mayonnaise sandwiches. When I was on my two feet and in high tops, rather than a high chair, it was my turn to set the table with silver heirlooms. My grandmother, like many of her generation, was more a keeper than a user of her collected things. With the simple gesture of setting the table with silver, my mother performed an alchemical transformation of “waiting for a special time” into “relishing right now.” With these spoons, my mother passed on the magic found in enjoying the present, the alchemy of finding the special in every day.

Using this tiny silver set, then, seems to me a kind of practical magic, a magic that lifts an ordinary meal into an extraordinary one. These demitasse spoons have the power to transform any dish into a beguiling one because of the dainty dining the scale demands. These spoons have the power to reveal the magic of the present as alchemical, as marvelously argentum: shining and bright.

What time is more special than this moment? This is the message passed on to me with the spoons. Whatever their monetary worth, the spoons have the unique kind of preciousness that comes from their passing through generations and transforming in meaning in that passing. My grandmother is now near the conclusion of her life, and my mother tends gracefully to her. These tiny spoons serve as a significant reminder to use and enjoy what we have, right now in life as we live it.

This story originally appeared in Issue No. 29, Fall 2023