Hungry in the Backcountry

Back in August 2010, I got to do a two-week artist residency in Gates Of The Arctic National Park & Preserve. I was a recent graduate of a science illustration program, equipped with my sketchbooks, paints, pens, optimism, and excitement for my first trip to the Arctic. I didn’t know then that the government doesn’t provide food for such backcountry trips, so I flew to Bettles with two pounds of coffee, outdoor gear, and my art supplies. I didn’t realize I was supposed to take my own meals. Once there, I had to scavenge together ten days of backcountry food from the tiny gas station-style selection at Bettles Air, consisting of junk food and MREs, or Meals Ready to Eat, that last forever and come in gray-brown bags as military rations. I scavenged the crackers, candy bars, hot sauce, and side dishes like rice and mashed potatoes. I also packed my hope and creativity.

For the first few days of the trip, I sketched by the Koyukuk River and gathered rocks until we packed our gear and flew into the Upper Noatak River to spend ten days traveling downstream in inflatable canoes. The pace of a backcountry artist residency is quite unique because there is plenty of time. Day by day, the four of us—two artists, a park ranger, and a park volunteer/photographer—set up and broke camp, portaged our gear to the river, and paddled, but we also had time to spend in a place, to take photos, to go for exploratory walks, to sketch, and to gather and share ideas.

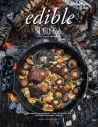

We enjoyed slow mornings sitting on gravel bars and evenings sharing food. We ended up pooling food resources and the volunteer, Richard, eventually became the camp cook. He had a lot of experience with wilderness float trips in Gates Of The Arctic, as well as other adjoining public lands. He spent a lot of the winter cooking and freeze-drying food, and was able to bring a pantry of freeze-dried ingredients in a few shopping bags to invent his own dishes each night. He combined dried vegetables with seasonings and some parts of an MRE and fed us all. I learned a lot from him, not just to pack my own food on government trips, but also how to outfit a pantry on a long backcountry trip. One of the great parts of this style of cooking is the flexibility to add local ingredients as you a find them: a handful of foraged berries in your oatmeal, or some wild greens in your curry dinner.

In the summer of 2023, 13 years later, I got to go back to the Arctic on another artist residency. This time I was working with the U.S. Bureau of Land Management and Toolik Field Station. Instead of flying to Bettles, we traveled up the Dalton Highway, and I marveled at the way this road provided access to some of the most unique backcountry areas. From there you can travel through the relatively small BLM corridor and go east into the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge or west into Gates Of The Arctic. Except for the Dalton Highway, there are no other roads in this area, which encompasses the largest roadless, protected area in North America.

In Coldfoot, I noticed the flurry of helicopter traffic and the buzz of people. A lot of work is going on now to plan and assess the proposed Ambler Road, which would stem 200 miles off the Dalton Highway west through Gates Of The Arctic to reach the Ambler Mining District. Roads are complicated and people have complicated feelings about them. They provide access and promise of potential economic opportunity. But we also have so many roads in our world and so many fragmented landscapes. There is something lost without places that are hard to get to, where the migration of animals and the endless miles of permafrost and tussock have precedence over human development.

Along the Noatak we found paths that caribou made on their migrations. We enjoyed cups of curry that were scraped together from freeze dried bags of veggies and parts of MREs and we watched the silver light of an August evening as a cross fox scavenged on the bank. We paddled past a pingo that was also a wolf den and watched curious pups stick their heads out to investigate us. We sat on a gravel bar and talked about making art to help people care about a place they may never visit, the existence of which, nonetheless, may give them hope and peace.