Making the Most of It

Chef Stacie Miller Offers Lessons in Weeding, Cooking, and Life

In the kitchen at McCarthy Lodge Bistro, Chef Stacie Miller shakes a jar glowing with dandelion petals suspended in vinegar. She opens the lid and takes a whiff with her eyes closed. “Slightly vegetal,” she says. “I’ll let it go a bit longer.”

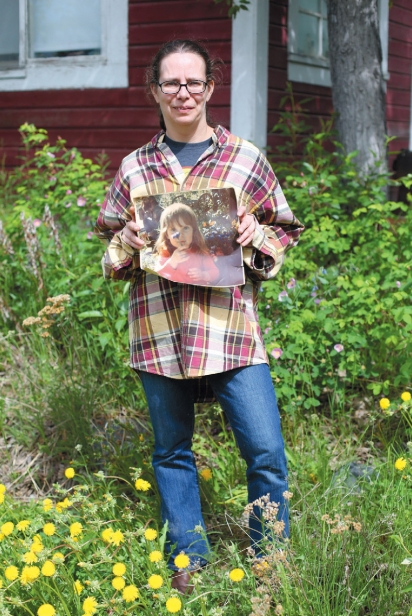

An array of wild foraged resources from the local landscape rest on the stainless-steel counter—petals, grasses, and various specimens that look suspiciously like weeds. Indeed, just before traveling to McCarthy, I was pulling dandelions myself from my Anchorage garden with militant vengeance. Miller, though, knows how to extract luscious color and complex flavors from these pervasive plants. Miller’s unique culinary use of Alaska’s wild resources comes from her childhood growing up in McCarthy, Alaska, a small community at the foot of the Wrangell Mountains. Miller is now the Executive Chef at Hearth Artisan Pizza in Anchorage after nearly 30 years living and cooking on and off in the community where she was raised.

I first got to know Miller through the Anchorage Museum’s Urban Harvest class series that connects contemporary Alaskan lifeways to their histories and contexts. In these classes, participants examine objects in the museum collection and learn hands-on from local experts in workshops that demonstrate continuity and innovation in growing, preserving, and cooking in Alaska across time.

Miller explored the history of fermentation in the first class she led. She included recipes and tastings of koji-inoculated salmon lox and fermented goat’s head, both of which were delicious. Since then, Miller has led many Urban Harvest classes, teaching people how to use local wood to cook in unexpected ways (think green birch wood to flour shortbread), or how to use all parts of a salmon. She’ll teach more classes this fall. “It’s important this information is passed down and preserved,” she says.

A childhood in McCarthy helped shape Miller into the chef and teacher she is today. Her parents Jeannie and Jim moved to McCarthy from Wasilla in 1980 when Miller was four years old. Jim’s mother was managing McCarthy Lodge and needed help with operations. Eventually, her parents took on a variety of jobs, including running the town grocery and a shuttle service for tourists.

Cooking was a family activity for Miller, her parents, and two brothers, but not necessarily always a family passion. Miller recalls that Jeannie and Jim would often play cribbage before dinner, and the loser would have to prepare the night’s meal. Stacie describes her childhood fare as “standard American”: meat and vegetables. The Miller family’s diet was perhaps a bit less standard than Stacie might claim, though. The 1980s brought the release of Bagel Bites, Lunchables, Lean Cuisine, and Fruit Roll-Ups. Meanwhile, the Miller family was baking huge batches of fresh bagels and donuts, fermenting crocks of sauerkraut, and making moose loaf and salmon from their own harvest.

Eating dandelions and other common garden nuisances was a definitive part of Miller’s childhood menu. Miller recalls making dandelion blossom fritters to be dipped into ranch dressing— not quite Cool Ranch Doritos introduced in 1986, though perhaps a similar idea of savory crunch and creamy tang. Miller recounted a family story in which her uncle refused a salad containing chickweed, saying he would never eat a weed. These formative experiences and flavors inspired her. “I love feeding people weeds,” she says.

Harvesting from the local landscape wasn’t so much a choice for the Millers as a necessity. The valley where McCarthy is nestled has never been a place of bountiful food resources. The Ahtna Indigenous peoples who have traversed and stewarded these lands for thousands of years historically travelled in small groups through this valley because fish and game were not bountiful enough to support large communities. Villages were established outside the valley where food was more plentiful, like Chitina and Taral on the Copper River.

When prospectors first arrived late in the 19th century, they struggled to survive. The Ahtna fed one party, guiding them through the valley and revealing rich deposits of copper ore the Ahtna used to make needles, tools, jewelry, and other goods. Word quickly spread of the abundance of copper, leading to the establishment of Kennecott Mines.

Lucrative copper production attracted hundreds of workers, all of whom needed to be fed. McCarthy grew up just a few miles down from the mine, providing goods and services (including alcohol which was prohibited in the mining town of Kennecott) to miners, mill workers, management, and their families. With land flat enough for a train to turn around, McCarthy became the site of a railway stop in 1911, making it an important commercial center with drugstores that had ice cream counters, bars, restaurants, and more.

Following the boom and bust cycles found throughout Alaska’s history, the exponential growth of this community was short lived, though it exceeded even the investors’ hopes. By 1938, nearly 5 million tons of copper ore had been extracted from the five Kennecott mines, depleting the deposits. The operation suddenly closed, and on November 10, 1938, the last train left with most of the area residents aboard.

A few families remained in the area, and another influx arrived in the 1970s around the building of the Trans-Alaska Pipeline and the kindling of the back-to-the-land movement. Nevertheless, according to the U.S. Census, over the past three decades the resident population of McCarthy has remained below 45 though an estimated 30,000 visitors come through the area annually. With lodges and restaurants, McCarthy has become a destination for tourists interested in exploring the abandoned mine site, and a romantic hideaway for Alaskan residents seeking a sense of the remote with the option for a cold beer and live music in the summer.

Because the land around McCarthy is rocky, icy, mountainous, and mainly not conducive to agriculture, so many food resources are brought in via the infamous 60-mile dirt road. The Millers, though, know how to maximize the land, growing vegetables and raising turkeys, chickens, and pigs. I visited the Miller compound where Jim and Jeannie still live, now a lush oasis with tiered garden beds and sturdy chicken coops strong enough to keep out bears. With only one other family nearby (which is to say 18 miles down the road), Stacie grew up with a sense of independence and self-reliance. She mushed dogs and butchered animals herself because, as she jokes, her brother faints at the sight of blood.

Miller built her own cabin—with help from family and friends— when she was 16. She’s a bit shy about inviting me in; she hadn’t been back in several years. She came back with plans to remove keepsakes and valuables so the cabin could be torn down. All around this loved structure are edible plants—currants, rhubarb, pineapple sage, chickweed, and yes, dandelions. Inside, the kitchen is clearly the heart of the home. Jars of spices are screwed into the base of the sleeping loft to save space; a propane fridge hums steadily. “It’s never once broken in all these years,” Miller says. Over a cup of tea made on her clean, efficient range, she tells me, “No matter what happened, I always had this place to come back to.” I know she means the cabin, and McCarthy, too.

Miller left McCarthy for college, earning an anthropology degree from the University of Alaska Fairbanks. She got her first kitchen job in Fairbanks knowing nothing about commercial cooking. In her interview, Miller told management she knew how to make everything on the menu. She went home, read The Joy of Cooking, and with the determination and spunk instilled in her from childhood, she managed to cook her way through. She met her friend Sue in that kitchen, who helped Miller learn her way around restaurant preparations. Sue is Korean and introduced her to new flavors. Sue brought in homemade kimchi and showed Miller how the familiar technique of making sauerkraut could be used to create entirely new flavor profiles from local ingredients, like Miller dandelion kimchi.

Miller took restaurant jobs throughout college, returning to McCarthy for seasonal summer work. She worked for the National Park Service and helped her parents, who started a pizza restaurant, serve more affordable, accessible food than the local lodges. Jeannie and Jim built out the restaurant themselves, bringing in all the equipment and developing recipes without any restaurant background; they simply wanted to fill what they saw was a community need. Once the pizza parlor closed, Jeannie continued cooking as the chef at Kennicott Glacier Lodge, where she still works as the baker.

After college and some international travel, Miller found herself cooking again (as she says, “making great use of that anthropology degree”). She worked at Snow City Cafe in Anchorage, and then eventually opened her own restaurant business in McCarthy. This eclectic establishment was The Pizza Bus, a People Mover bus converted with an oven. The full-service Pizza Bus served gourmet pizza. Miller even delivered within a reasonable radius by four-wheeler.

Soon, Neil Darish, proprietor of the McCarthy Lodge and a number of other businesses, brought Miller on as chef. Plating multi-course fine dining meals for locals and tourists alike (and eventually even reality-TV crews filming in McCarthy) Miller always sought to incorporate foraged fare into her dishes. Darish glows when asked about Miller. “She really knows how to use ingredients because of her experience in McCarthy. She’s something special.”

It’s true that Miller has a special approach to cooking. She knows how to manage missed shipments of supplies, dogmatically avoids waste of hard-to-come-by ingredients, and draws exquisite flavors from the weeds around her. As she herself says, she would crush the competitive TV cooking show Chopped. Her mother Jeannie, overhearing this remark, chimes in: “You sure would. But tell them you can only do it if it airs in winter, though, when I can get satellite!” Summer foliage blocks reception.

After several days of foraging and experimenting in the kitchen, it is time for us to leave McCarthy. Miller makes plans to come back again to do a final clear of her cabin before it gets reused for firewood. On our way down the dirt road, Miller asks that we make a quick stop to harvest a plant she has grown up calling wild sage.

A few miles outside of Chitina, we pull over to gather Artemisia frigida. As we gather, Miller teaches me about the plant, and how to use this roadside herb’s best parts for teas, meat rubs, and more. I cannot help but notice that her foraging bag is surprisingly familiar—a gift bag from the Anchorage Museum shop—not staged, she promises. Her always-teaching approach is familiar, too, from the Urban Harvest classes she leads at the museum. Bags full, we load into the car, soon overtaken by the sage’s vibrant smell. On the six-hour drive back into town, Miller works on drafting menus while turning to the window every once in a while to soak up the view of the mountains.

Miller approaches cooking with a sense of pragmatic humility, the same sensibility that has led her to create food that is uniquely Alaskan and uniquely her own. Now, she brings these approaches to Anchorage at Hearth, concocting innovative pizzas and specials that feature locally sourced ingredients from hydroponic salad greens from Seeds of Change to spruce tip salt made with spruce tips Miller forages herself.

As we drive towards Anchorage, it strikes me that McCarthy is indeed a place Miller can always return to—whether to visit that familiar landscape, or simply to draw on her experiences there to inform what she cooks up. McCarthy adds a flavor all its own to what she creates.

I return to my Anchorage garden with a different view of the dandelions growing between my raspberries, beans, and herbs. Instead of tossing them to compost, I pluck the flowers for fritters, dandelion wine, and petal cookies; I gather the greens for stir fries and ferments. In this way, Miller inspires me to see my own little Anchorage garden with new eyes, and she shares that same inspiration through mentoring at the restaurant and in teaching Anchorage Museum classes.

Miller has shown me how to eat my weeds. This is a process beyond trying to make use of what would otherwise be discarded. Truly harvesting “weeds” means looking closely at what is growing, learning about the plants, and coming to appreciate every aspect of the landscape’s bounty. And it’s true—once they are on the menu, weeds aren’t such a nuisance.

Perhaps this is not just a lesson for the kitchen, but a way of closely looking at experience, learning from past and present, and making the most of it—enjoying all the flavors life has to offer. As Miller says, “You know, life has been pretty good … so far.”

Learn from Stacie Miller at upcoming Urban Harvest classes at the Anchorage Museum including a September 17th class on crabapples. More information available on the Anchorage Museum website. Visit Hearth Artisan Pizza to taste Miller’s current culinary creations.