Pushing Limits

Driven by a warming ocean, Pacific cod swim to the northern rim of the Bering Sea to keep cool. Fishermen seem to follow.

Here in Nome, the ocean slides to shore, carrying a light wind to the seawall lining the coast. On this August evening a high sun emerges from behind prevailing cloud cover, brightening the deep blue whitecaps of northern Bering Sea.

Not far away at port, Adem Boeckmann, who moved to Nome in search of gold at age 15, is aboard his fishing vessel F/V Anchor Point preparing to pull king crab pots.

But another species—cod—is on his mind, and people are talking about the white fish fillets around town, like inside Polar Café, the greasy spoon on Front Street.

Last summer was the first in Nome that the local seafood processor targeted cod for purchase, according to Boeckmann. Before that time, cod were an afterthought compared to highly valued king crab. “We’re kind of on the cusp of it,” he said about a shift in the surrounding sea, and fishing practices will have to follow suit to survive.

Or perhaps the cusp has already been crossed. A paper published in Evolutionary Applications last October indicates that the Bering Sea is transitioning from an arctic to a subarctic ecosystem. And this shift means a northerly movement of oceanic species to resemble the marine subarctic ecosystem previously observed farther south.

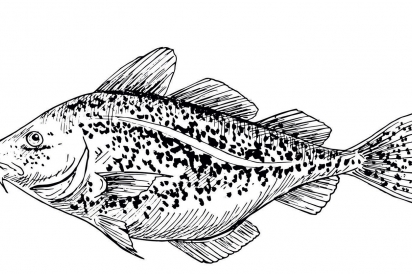

This migration includes commercially valuable, and tasty Pacific cod (Gadus macrocephalus).

This fish species was previously common south of here, but now Pacific cod are being caught in the northern reaches of the Bering Sea outside of Nome. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) contends that Pacific cod have recently migrated 1,000 kilometers north of their normally expected summer range.

Crab and halibut are more traditional catches from the Port of Nome. Pingo Bakery and Seafood House, a small, warm space with Western Alaskan comfort smells and meals, serves a halibut pizza, seafood omelet with king crab meat, red salmon fish and chips, and even oven-baked macaroni and cheese with marine add-ins. On today’s menu, too: Pacific cod chowder.

Movements of Pacific cod populations impact fishers like Boeckmann, and inspire local menus. The shifts disturb the global food web, too.

Nutrients, energy, and water are essential components of food chains, according to a recent article published in Ecosphere. When we consider food chains, we ought to examine the base of the chain, like nutrients and bacteria in soil or phytoplankton in the sea, as well as top predators from humans to salmon sharks.

Terrestrial food webs include cultivated and wild growing plants and consumers on land, though freshwater and marine ecosystems are also composed of complex food webs. Terrestrial and aquatic food webs interact and overlap; changes in global temperatures are expected to impact the interconnected global food chain, according to this recent paper, and other studies.

In 2009, more than 500 miles southeast of Nome in Kodiak, 8.48 million pounds of Pacific cod were landed at port, according to the Alaska Department of Fish and Game. A decade later in 2018, Kodiak harvested just 1.17 million pounds of the whitefish. This is a 700% decrease in fish landings over a ten-year span, and at first the 7 million pounds of Pacific cod were unaccounted for.

After a rapid response research survey in 2018, Lyle Britt, fisheries research biologist with NOAA, said data indicate there’s been a roughly 900% increase in Pacific cod biomass in the northern Bering Sea survey region.

“Now we didn’t think it was going to be at the scale we’ve seen here in recent years, or that it would even happen this fast,” said Britt, referring to the northerly shift of fish.

Pacific cod are also called gray cod due to their coloration and can be identified by a whisker-like, barbell organ that extends from their chin. They live for 20 or fewer years, and an individual female can produce more than 1 million eggs each spawning season.

Last year, king crab fishing was miserable, Boeckmann said. “They weren’t there,” he said. His theory: King crab don’t like the warmer waters that Pacific cod seem to have followed. If the entire Bering Sea ecosystem is shifting from an arctic to subarctic zone, king crab are bound to be impacted, too.

According to Boeckmann, people are traveling from Dutch Harbor, an island town slung down the Aleutian Island chain, to fish for Pacific cod around the Diomede Islands, some miles of travel north, over rough ocean.

The two islands jut from the ocean like a green or frozen semicolon, to spot the narrow pass between Russia and Western Alaska. “The Diomedes sit in the middle of the Straits like old guards most always shrouded in a mist,” Boeckmann described. The marine gap between land masses, known as the Bering Strait, is the passage where water from the Bering Sea rolls into the cold Arctic Ocean, then back again.

According to the World Population Review, the town of Diomede’s population in 2019 was 119 people—all of whom were Iñupiat Indigenous Alaskans. There, locals consume birds, seals, and walruses. In 2015 the only aircraft to Little Diomede was grounded for three weeks in spring, meaning no food went in, and people couldn’t depart.

North of the Bering Strait, commercial fishing was closed at the time this article was written, in December, pending further research. As the Arctic warms, these waters are becoming ice free for part of the year, meaning they could eventually open to commercial fishing.

On a king crab mission this past summer, Boeckmann unintentionally pulled Pacific cod up in his pots. And that wasn’t his only unusual encounter in the Bering Strait.

“It’s a beautiful day, flat calm, glassy— and out of the corner of my eye, what do I spy? About an 8 or 9-foot salmon shark,” Boeckmann said. “I’ve never seen a shark in my entire life and I’m sitting here in the Bering Straits, just… under 20 miles away from the Arctic Ocean, and there’s a shark.”

Boeckmann can’t keep both crab and cod in the same holding tank for travel back to Nome where he sells his catch. So on that fishing trip, disheartened by the lack of king crab to weigh down his boat, he tossed caught cod back to sea.

While Boeckmann has historically fished for financially valuable king crab and halibut, he said he’d consider targeting cod. But in order for the whitefish to become lucrative catch, the fish would need to be taken in high quantities, and from larger boats than his with adequate storage. Fishing for Pacific cod would also necessitate a restructuring of seafood processing plants to accommodate the changes in species, and high volume of seafood landed.

This tests how adaptable humans are to a shifting ocean, and food chain.

Fish processing facilities are already steaming north, according to several people who’ve fished the Bering Sea for years. Boeckmann heard that a floating processor—a ship that buys fish directly from boats and slices them on board, and has the ability to move as quickly as fish can swim— will soon make its way to the Diomedes where Pacific cod are being harvested.

Sometimes Boeckmann keeps his cod catch. “Head ’em, gut ’em, and bleed ’em, slush-ice ’em… and keep ’em nice and cold,” he described of his current fishing practices. “And give ’em to friends of mine who love Pacific cod… And they are a fantastic Pacific cod, and like all of the fish in Norton Sound, a little better than all the other fish in the world.”