A Recipe for the Future

Originally published in Issue No. 23, Spring 2022

Indigenous people make a profound connection with their homelands when eating traditional foods provided by the land and water. The act of traditional eating supports and nourishes an intact relationship with place. I would even go so far as saying that the practice of Indigenous foodways is directly tied to well-being. Our current food systems’ governmental regulations, meant to protect people from pathogens that might cause sickness, cause other problems when people are kept from eating traditional foods that they cherish and look to as cultural identifiers. Cyrus Harris, from Sisaulik and then Kotzebue, has worked to navigate regulations that have barred his people from partaking in their traditional foods. The model he created could be applied to other regional hubs around Alaska.

Harris says that he received his field education from his home in Sisaulik. It was there, 14 miles across the Sound from Kotzebue, that he learned to hunt for ugruk and natchiq, the seals that provided for his family. The meat from these seals is high in iron, and the oil from their blubber is full of vitamins A and Omega 3 and 9 fatty acids. Harris was able to live in Sisaulik and support his family with hunting, bartering, and trapping fur until the value of furs diminished as fuel costs rose. This pressure led Harris to move his family into Kotzebue in the late 1980s when he found work with his regional tribal health corporation comprised of 12 tribes named Maniilaq Association for the Iñupiaq prophet and healer. Like so many Indigenous people in Alaska, Harris describes his existence as one of ‘’living in two worlds,” but being in conversation with him makes clear that his values are rooted in the Iñupiaq way of life, and his work conveys these values to all who witness and benefit from his efforts.

In 1993 Harris put his knowledge to work by developing Maniilaq’s Hunter Support Program which was intended to provide food for elders and others in need by giving hunters who share their catch fuel, ammunition, and motor oil. The program was started with Federal Title VI funds which were meant for purchasing cafeteria foods, but Harris knew that commodity foods would not bring the elders intended health benefits because they were not accustomed to eating non-traditional foods. By re-working the funding directives to suit the needs of Iñupiat elders, the Hunter Support Program provided the benefit of traditional foods that are tied to the land and way of life of the elders and hunters. The program quickly grew and was implemented by all 12 of the tribes in the region.

For every achievement it seems that Harris was also beset with pitfalls and only two years after the Hunter Support Program was underway a government shutdown cut off the funding that made the program possible. To keep the program going, new funding streams were found, and the State of Alaska was able to close the gap with money from Elder Services. When the State cut Elder Services two years later, the Maniilaq Board pulled from their general fund so that the Hunter Support Program would not be interrupted. To this day, Maniilaq is the primary source of funding for the Hunter Support Program.

When a senior center was built in Kotzebue, organizers had to create a way for the traditional foods served there to be inspected and stored safely. Harris and his colleagues directed the building of The Sigluaq; in Iñupiaq it is the word for a traditional ice cellar dug into the permafrost to store food. The Sigluaq was built to code for proper inspection, processing, and storage of foods according to Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation standards. Now Harris can accept donations of game animals that are in quarters or larger which he then inspects and breaks down into various cuts for distribution to where they are needed.

Likewise, when the long term care facility in the hospital in Kotzebue was established, Native foods were initially not allowed in that wing. Harris found a loophole that allowed Native foods, or niqipiaq, to be served to elders by having monthly potlucks, but he was deeply frustrated by the fact that seal oil was not allowed to be shared at these food gatherings. He worked within the framework of the Farm Bill in 2015 to add language that allowed traditional foods to be served in long term care facilities more frequently than once a month at potlucks, but the section that allowed for these foods did not supersede the prohibition on seal oil from being served in this setting because of the perceived threat of botulism associated with a few isolated incidents that have occurred in Alaska.

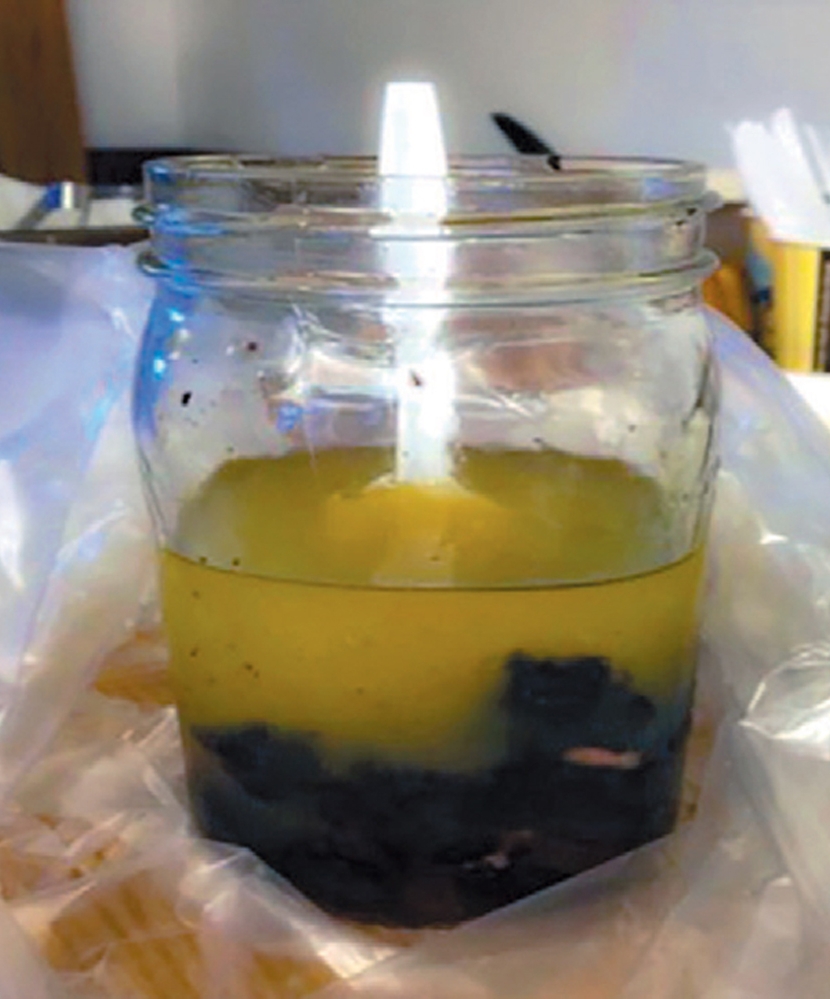

In response, Harris formed the Seal Oil Task Force with experts in botulism from as far away as Wisconsin and The Sigluaq became a science lab for seal oil. Harris and his team worked at rendering seal oil in the traditional way of the people and experimented with other methods, but there was one item that continued to be a sticking point: the pH level of the oil. When oil is rendered from seal blubber in the way of the Iñupiat, no heat is applied. Harris and his team tried a number of ways to bring the pH down to Centers for Disease Control recommended standards, but in the end the only thing that satisfied the pH level requirement was pasteurization. After rendering in the traditional way, the seal oil is pasteurized in small lots and jars are labeled with the seal species, lot number, date. On the back there is a nutritional label with serving size, calories, and nutritional attributes, just like one would find on a jar of oil in a grocery store.

When I commented on Harris’s tenacity, he said, “We never stopped, we never gave up.” He continued, “Let’s put it this way, I am trying to pave the way in case I end up in the senior center. There is no way I will be able to live in long term care without my seal oil.” As we were wrapping up our time Harris got a call and felt it would be beneficial for me to meet the woman on the phone because she was calling from the long term care wing of the hospital. Lisa Adan works for NANA Management Services and is responsible for cooking for the elders housed there. She called to request more meat and fish from

The Sigluaq and was hoping that there might be some fish eggs for somebody who requested them. Lisa said, “You can tell the difference when the elders are eating their traditional foods. They are out and more active and sleeping well.” She went on to say, “They are sitting here waiting for the food to be done because they can smell the food.”

The first Sigluaq Symposium was held five years ago to share the successes and hurdles that had to be navigated to bring traditional foods to elders in long term care, but it was prior to the use of the seal oil pasteurization process that led to being able to safely provide this vital food to elders in care. A second symposium was scheduled to share the success story of The Sigluaq, but it had to be cancelled because of the pandemic. The idea is to share the successes as a template of sorts so that other hub communities with long term care facilities might benefit from what had to be learned the hard way over the life of the Hunter Share Program under Harris’s guidance. Harris says, “It’s like a recipe,” and I love how this work that touches upon so many traditional values from the past can be encompassed so succinctly. It is a recipe for goodness that can bring core values of respect for the people, culture, land, waters, the food the land and waters provide, and sharing for the benefit of all that is needed for a bright future. It is a recipe for wellness.