Salmon Skin: June Pardue Reinvents and Reclaims an Important Alutiiq Tradition

June Pardue Reinvents and Reclaims an Important Alutiiq Tradition

June Pardue is a celebrated Alutiiq elder and fish skin tanning expert. I’m a white lady who grew up in Ohio.

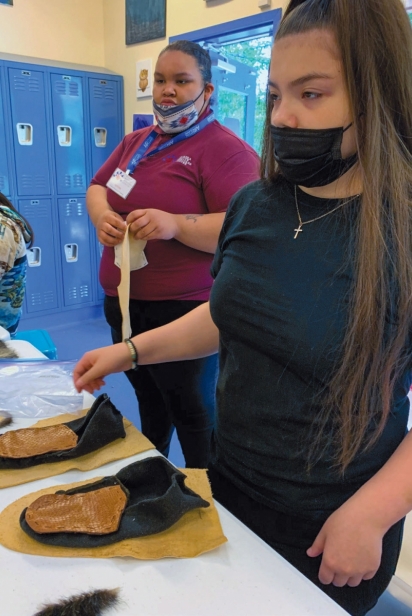

Pardue and I address this right away, verbally and nonverbally, when she asks me where I’m originally from. This introduction, after months of emails and phone calls à la COVID, occurs amidst the quiet buzz of a workshop underway. The sun floods through an open classroom door in the Alaska Native Heritage Center. Tours proceed through the green grounds just outside, while performances and activities echo in the halls behind us. Sumptuous, caramel and syrup-colored bits of soft sea otter fur and tanned salmon skin lay on a large table where a handful of interns snips and sews away on slippers. Hands bend, pinch, and sew together the supple but sometimes stubborn materials, and Pardue herself sews in a dizzying, syncopated rhythm akin to waves moving in and out. Interns listen and watch her intently in between their stitches, and every so often, someone sidles up to her to quietly and respectfully asks for assistance. Throughout all of this, Pardue calmly tells me where to stand and where to look as she teaches and works, weaving in small loops of conversation with thoughtful precision as though she’s directing our limited time through tiny needle eyes.

Pardue—and it is Par-due, not Per-due, as it’s often mispronounced—is known across Alaska and beyond as an Alutiiq and Inupiaq artist and teacher, specializing in grass weaving, fish skin tanning, sea mammal sewing, jewelry making, and beading. She has immersed herself in these practices and materials, the same that surrounded and were revered by her ancestors; she’s honed and shared her hard-won skills and knowledge for over 50 years. Her work is installed in major museums. She’s given lectures and demonstrations at the United Nations in New York, the Smith sonian’s renowned FolkLife Festival in Washington, D.C., the Autry National Center in Los Angeles, and the State Hermitage Museum in Russia. She’s frequently invited to remote locations throughout Alaska and connects with people from all over the world as together they work to reclaim, revitalize, and even reinvent, out of necessity, cultural practices that were nearly lost during long and devastating periods of violence. One of these practices turns sequined, scaly, slimy fish skins that would otherwise be tossed to the gulls, into an impossibly soft, sturdy, sweet-smelling textile as though by magic. That is what June’s interns are sewing onto the top of their slippers today: tanned salmon skin.

“THERE WAS NO ONE TO TEACH ME.”

As inhabitants of Alaska—natives, settlers, visitors, guests—crossculturally, we are undeniably salmon obsessed. It’s an undercurrent of life here, one that sometimes unites and sometimes divides us: how we obtain, use, and protect this resource that swims in the oceans, fights up the rivers. Even viewing salmon as a “resource” (“a stock or supply that can be drawn upon by a person or organization in order to function effectively”) isn’t accurate, and may run counter to all that salmon is to many Alaskan communities. Fish skin tanning, or turning fish skins into a soft, breathable, water-repellent leather, was and has been an important part of many seaside cultures. Salmon skin leather is used in a wide array of art and functional items, like clothing, by nearly all Alaska tribes. But what happens when there is an interruption in—an assault and encroachment upon—this transfer of cultural skills and knowledge? On an entire people and way of life?

Salmon has certainly not been the only resource to lure travelers to Alaska. Pardue grew up in Old Harbor on Kodiak Island, a village of about 200 people today, where furs and the skills of native hunters and trappers were once sought-after prizes. If you look on a map, you can see it’s on the southeastern edge of Kodiak Island opposite of Sitkalidak Island and Refuge Rock (Awa’uq). In the spring of 1784, Russian fur traders launched an armed assault on that island, killing hundreds, possibly thousands of Alutiiq/Sugpiaq people. What followed was a century of subjugation and mistreatment that, among other results/consequences/ ends, nearly wiped out many sacred customs and art that had been passed down for generations. “I think the women that were able to survive at that time were doing just that, surviving,” Pardue says of the latter part of this period, and why she thinks salmon skin tanning and other traditions seemed to all but disappear in daily life. “Our men were enslaved, they and their children were held hostage, and they had to do everything to provide for their families, and try to ensure their safety. Women suddenly had to hunt, build kayaks and canoes. And I think, too, and this is just my opinion, they thought, why should they share their skills if they didn’t have to, and further help the people that were hurting them in any way.”

In short, art-making, skilled crafts, and sacred customs that would be passed down to younger generations fell to the wayside. Pardue says when she was growing up, aside from a few women practicing Alutiiq basket weaving, no one was doing any traditional art. This seems to align with the experiences described by many in her generation, whose parents were sent to boarding schools at the behest of the U.S. government in the 19th century, further stunting the use and teaching of vibrant language and traditions within Alaskan Native communities. Pardue says she remembers visiting museums and seeing art and artifacts of her people in detail for the first time. “The tanned salmon skins, the beadwork… they were all behind glass, untouchable.” She wanted to learn these arts “but there was no one to teach me.”

It would soon become Pardue’s mission and life’s work to reconnect herself and others with these invaluable pieces of the past and of themselves. To learn, she had to get creative in her research and experiments, most especially when it came to tanning salmon skins.

“WE HONOR THE EARTH AND KEEP IT CLEAN.”

Alaska has no shortage of salmon recipes for all things food-related, but there were no readily available recipes for salmon skin tanning solutions. With no one to teach her, and only the encouragement of her husband and family, Pardue set off looking for clues and information from a wide variety of sources—mammal skin tanners, other Alutiiq artists, people she met through various workshops and travels. She found people who “tanned” salmon skins, but they only dried the skin into something like crispy rawhide, adding oils after to soften them. “The problem with this is that it’s not really tanning. It’s not leather,” she explains. “Those materials will eventually rot. And they will smell.”

As Pardue and her husband got closer to developing an effective tanning solution, they discovered another challenge: how to create an environment-friendly recipe that aligns with their Native values. “We have respect for the animals and the land; it’s part of our culture that we hon or the earth and keep it clean.” One man they met tanned snake skins, she says. “It was a family recipe using alcohol and glycerin, and he would sell those skins. But this recipe was for a reptile, not for a fish.” They also felt uncomfortable disposing of the solution. Fireweed greens, berries, alders, and cottonwoods used for smoking, birches used for syrup—all of these would be affected by any harsh chemicals they tried to dispose of. “We want to ensure that our water and air sources remain clean.”

Eventually, they successfully developed their own techniques and recipes using natural, locally sourced ingredients, ones that were gentle but effective, and could be poured right back into the earth. Pardue has continued to experiment and share all that she has learned ever since. She now knows that the age of the salmon affects the quality of the leather. For example, “older fish skin is thicker and more tough—it takes longer to tan and is better for dog packs or containers.” They discovered that alder used for tannic acid produces a tougher, darker leather, and that spring is the best time of year to harvest willow bark, her preferred ingredient in her tannic acid. “I start off with a weak homemade tannin using new-growth willow and strengthen the solution over a period of ten to 21 days. It produces a beautiful, soft leather and we can dilute and dispose of the tannin easily and safely.” In fact, she says the tannin even acts as a highly effective fertilizer, especially to her strawberries.

“HOW EXCITING IS THAT?”

Pardue has a busy schedule these days. Besides making and selling earrings, barrettes, slippers, baby mukluks, and sewing bags out of her tanned fish skin, she is a mother, grandmother, and great-grandmother, and sees her family often at her home in Sutton. She is an adjunct professor for the University of Alaska–Kenai Peninsula College, University of Alaska Anchorage, Alaska Pacific University, and Mat-Su College in Palmer. She also sells salmon skins as a distributor, using her expertise to source quality tanned and dyed salmon skins from around the world for local buyers.

Pardue is also a cultural developer and instructor for the Matanuska-Susitna Borough School District and an Elder Culture Bearer for the Knik Tribal Council. She has taught at the Alaska Native Heritage Center since it opened in 1999. She travels to culture camps in remote villages all over Alaska in the summer. During times of isolation, she has offered classes remotely, serving many Alaskan Native communities, traditional native councils, native corporations, and wellness programs in addition to individuals from all over the world, from museum curators in London and Italy to tanning enthusiasts in Scotland and Canada. “I love meeting people from all over the world and it’s just absolutely FUN to gather with individuals who are genuinely enthusiastic and interested in turning fish skins into leather. I’m especially excited that young people and youth are wanting to do this too because they will be the generation who remembers that their elders tanned fish skins. How exciting is that?”

She was recently interviewed by Good Morning America and, just before the pandemic, led a major restoration project at the Alutiiq Museum, where she and her team recreated a beaded Alutiiq headdress that was shipped over from France (it had been acquired by a French expeditioner in 1871 during his travels along the Alaskan coast). This project was documented in a short, award-winning documentary titled Pinguat. In the film, she says of her team, “I can see the hunger in their eyes and the eagerness to want to learn.” The sentiment rings true for her interns today at the Alaska Native Heritage Center as well.

The interns are all in their late teens or 20s, and come from varied locations and backgrounds. “I came into this internship as a city kid,” says Isabella Badwarrior. “I am Cheyenne River Sioux and we work with buffalo skin, like we are here today in class. I was able to connect to my past, with culture and traditions through Ms. June,” Badwarrior says, as she holds her slippers and adds that this is the first time she has made or even owned anything authentically Native. Another intern, Antilleon Atcherian from Chevak, says of Pardue as a teacher: “She is direct and she is kind and just wise. She really works with you in this very professional, knowledgeable way.”

“The most challenging part is the toe,” says Esther O’Brien as she sews her slippers. O’Brien’s family lives in Old Harbor, the same village Pardue is from. “I appreciate Ms. June. Being with her is like being with an elder or family member in our village. It reminds me of doing beadwork with my grandma there.”

Pardue notes, “When I sense doubt, I tell them our ancestors did it, so can we. I want us to have the same pride they had when they were creating.” She says learning these skills incorporates values, self-worth, and wholeness into their lives. “I want youth and culture camps to learn the art of turning fish skins into leather so it can be fully revived and used as a sustainable art practice for additional income in villages and remote parts of Alaska.”

“REMAIN TEACHABLE.”

I watch Pardue with the students. She shows me a tanned salmon skin before it’s been softened; it is a split, splayed out, symmetrical headless fish, brown and smoky-sweet smelling, soft but unyielding. She shows me a pair of mukluks she has finished, lets me hold them, look at the artful, colorful embellishments, touch the fur accents, feel the salmon leather vamp in its finished form on the top of the foot, the scale patterns still present but everything soft and supple. I have never seen salmon this way. I watch her share tips with her students on basting, for sewing heels and toes, for trimming welts. There is so much to cover and they are slightly behind schedule, but everyone is focused and happy, fully engaged. “It really means a lot to me, to get together and work like this, like they did a long time ago,” Pardue says in the documentary, and that’s exactly what I feel in the room now. The fact that she finds any time to talk to me throughout this lesson is, again, a testament to her creative and resourceful spirit, as well as her skilled and dedicated teaching. She knows each student and I can see that she saw that I was a student, too, before I did, that I knew very little. Any quality teacher or student knows that “educating” yourself only goes so far; that we need an honest exchange to fill in the gaps and missing pieces before we even know what questions to ask; that it might not be in any of our best interest to treat the stuff we might usually step around or throw out—salmon skins, sensitive topics—like they’re off limits or behind glass. Maybe we need to touch things, get a little messy. In a world that seems to relentlessly seek and reward assuredness and shows of strength, when it comes to healing and reconnecting with the past to create a better future, maybe we need those who remind us to stay soft, malleable, and curious to lead the way.

As Pardue’s parents told her throughout her childhood, as she still says to herself and her students today: “Remain teachable. We don’t know everything and there is something to learn every day.”

Originally published in Edible Alaska Issue No. 22, Winter 2021