See the Forest for the Mushrooms

It was early June in the boreal forest—too early for bolete mushrooms—plus it hadn’t rained in days. The last thing we expected to see on the forest floor was a plump, firm bolete, but there it was. Its rounded brown cap resembled a big potato cast onto last fall’s leaf litter beneath tall, bear-scratched aspens. It was a delightful surprise and a portent of big fall bounties to come later, on the far side of summer solstice.

Friends in other parts of Alaska were finding droves of morels—I’d found just two modest ones on my property and heard that others nearby had come across some, but not many. The lone bolete seemed healthy, firm, and decidedly harvestable. We decided to wait, though, figuring we had more time before insects or rot ruined it.

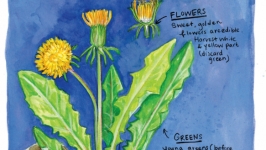

I’m at best a mushroom novice, an inexpert but careful appreciator. Thanks to friends, I’ve learned to identify a handful of species. I refresh what I think I know every year with crosschecks in field guides and conversations with my betters. I harvest some on my own (chicken of the woods, oyster mushrooms, orange delicious, bear’s head, and those aforementioned). Others I know to be poisonous. Showy, ornate, and deadly, they’re like some of the wildflowers that grow here, too. Nearly all the flowers are beautiful in some way, with some (bluebells, wild rose, fireweed) offering edible parts. Others are poisonous to eat, but beautiful to see (monkshood, lupine), packing punishment for anyone who might fail to learn the nature of things.

Walking back to the cabin, the fresh surprise of that early mushroom kept my eyes alert. I noticed the dainty pink bells of lowbush cranberries already blooming, and the dual symmetries of twinflowers—some dangling one open flower and one bud. I admired the red color of the pink pyrola’s stalks supporting a dozen half-inch flowers, all sporting a long style. White and green dogwood grew like paisley fabric, carpeting parts of the forest floor. I took care to avoid trampling the lowbush blueberries so rare in these parts.

That early bolete—scout of fall, harbinger of meals, reminder to see—summoned memories: The earthy smell of Jessica’s hot cabin as she dried morels harvested in the Chakina wildfire burn. Brita and Tyler’s massive August haul—pounds of mostly wet orange delicious that we rendered down to a delicious gravy. A fine coral mushroom cupped in Nina Elder’s hands, which we spotted on the return leg of a 22-mile mountain biking trip out to the Nizina River.

Gaining sight of the cabin, I remembered the huge squirrel cache of dried mushrooms I found in the loft of my oversized arctic entry late last fall—hundreds of small and medium-sized mushrooms of all kinds carefully dried and hidden. As annoying and destructive as squirrels can be, I was impressed at the little prepper’s industriousness. Squirrels are the only mammal that can digest poisonous mushrooms, and they eat quite a lot when they can. As I cleared out bushels and bushels one cold night on the cusp of winter, I realized I might be setting doomsday in motion for that particular neighbor.

In Alaska, we can take fleeting glimpses of wild animals and birds for granted. That their lives are long and complex but glimpsed only briefly or occasionally makes each encounter exciting. There’s something in the experience of spotting a good mushroom in the wild that reminds me of seeing bears, moose, Wilson’s warblers. While mushrooms belong to the fungi kingdom, as opposed to plants or animals, they are more closely related to animals than plants, genetically speaking. In a way, eating a bolete is more like eating a squirrel than a potato.

Still, comparing a mushroom to a berry seems most apt. Mushrooms are to some fungi what berries are to berry plants. Instead of seeds, though, mushrooms produce millions of spores in pores or gills beneath their caps. Spores spread and germinate, creating networks of microscopic, thready roots called mycelia that infiltrate their food sources. Mycelia live for years, unlike the ephemeral mushrooms we foragers mark time with through part of each season.

The lives of mushrooms are short. It can feel lucky to see them at all. They can’t run from us like bears, hide from us like wolves, or swim past unseen like salmon in silty rivers. They can grow and decompose in a few days while we aren’t watching, though. When we’re lucky to happen upon that process at the right moment, walking a trail one evening, say, we might discover some part of dinner or breakfast rendered up from a patch of ground that was foodless just days prior.

We did return to that lone bolete the next night. It remained unharmed and healthy, tempting and ripe. I severed its stalk just above the ground, leaving its mysterious mycelium undisturbed beneath. I shucked its soft gills from the meaty cap and tossed them in the forest, imagining a storm of spores swirling and settling all around. We carried the mushroom home and sliced it up along with peppers and onions, prepared dough and sauce, and baked a bolete pizza. It was a simple and tasty meal, and a good night to eat outside on the deck, contemplating how different the woods would feel without the occasional windfall of unexpected wild mushrooms.

Editors’ Note: This essay does not serve as guidance on foraging mushrooms whatsoever. Consult an expert before eating any wild food. Many mushrooms are poisonous. Some are deadly. Many species are easy to confuse for another. Some affect different people in different ways. Forage responsibly.