Where You Are: The revolution starts at home

BY S. HOLLIS MICKEY IN CONVERSATION AND COLLABORATION WITH JESSICA BISSETT PEREA, PHD SPECIAL THANKS TO AARON LEGGETT FOR ASSISTANCE WITH DENA’INA LANGUAGE TERMS.

When we think of foods that make us feel at home, we often call forward their flavors and smells, sights, and textures. But what about the sounds of the foods that fill our bodies and spirits with sustenance? Interdisciplinary musician-scholar and professor Jessica Bissett Perea reminds us that food involves every sense, including the auditory experience of eating, alongside the gustatory.

When we hear the satisfying crunch of crisp salmon skin, notice the squeak of a fresh spruce tip between our teeth, or tune into grooves of vinyl to set the ambiance for dinner, we are actually feeling pressure waves. These sound waves are movements back and forth, which in turn, move our eardrums, creating what we hear. The foods we hear move our bodies. The foods that bring us to a sense of home move us, literally and metaphorically, into a sense of belonging.

When I ask Perea about her earliest food memories, she says, unequivocally, “Berries, berries, berries.” Growing up in what is now called the Mat-su Valley, she and her family would hike into Hatcher Pass to load buckets with the tart treat of Alaska blueberries. This family outing to Qughun Betnu (Dena’ina for Upper Willow Creek) was special. “You felt like the entire expanse of the mountains was yours,” she says. There, nestled between the arms of what is now called the Talkeetna Mountains, she and her family would settle in to dine directly from the bush in situ amidst the landscape. “We have these pictures of buckets full and purple faces.” She remembers freezing the berries to be plopped year-round into baked goods and pancakes. But, she recalls, “Part of me thinks not many of them made it home to the freezer.” Smiling, she says, “It was a wonderful feast for the day.”

For Perea, who is of Dena’ina heritage, gega Upper Cook Inlet Dena’ina for mountain blueberry as one finds in Hatcher Pass) connects a past far beyond childhood to the present. And, Qughun Betnu is a place rich with memory. The tangy sweet of gega is a taste which connects time immemorial, and the soft, reverberant sounds of Qughun Betnu that echo now.

Perea currently resides with her family on the land of the Ohlone, in Northern California, where she is Associate Professor and Graduate Advisor, Department of Native American Studies, at the University of California, Davis. There, she also co-directs the “Radical and Relational Approaches to Food Fermentation and Food Security.”

When we speak, she is in her home surrounded by books, an electric bass behind her in the frame of her Zoom screen. From this place, she reflects on the notion of homegrown. “Homegrown is something that, when you think about the Valley, where I come from, and the farms, versus what our ancestors would have eaten since time immemorial… it’s a complicated story.” Perea wore Alaska Grown sweatshirts in college and took pride in sharing the extremes of large vegetables of Alaska’s summer with others, having left the state to play jazz music. “Just thinking about the things I didn’t know growing up— that history I learned after leaving the state—it’s been a re-education of looking at homegrown differently, considering what agriculture literally has to clear away to make way for things that are not indigenous to the place and, to varying degrees of success, do or don’t grow.”

For Perea, that re-education and reclamation have come, in part, through the resonant layering of music, language, and song—through listening, being in conversation. She affirms, “It’s always been traditional for us to be contemporary. And so, in that, I was able to let go of some of the shame of what I did or did not have growing up and start thinking about how I have agency in reclaiming and doing that work now.” More recently, the Radical Fermentation Dialogue Series she co-facilitates, has brought foodways into concert with these ideas.

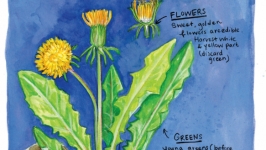

In these pages is a scene from Perea’s childhood. Those readers familiar with gathering plump Alaska blueberries on a mountainside can imagine the tart taste, the sound of wind which tussles her hair. When Perea recalls those moments of purple-faced family harvest, she also remembers the sound of the place. “When I try to meditate, I do often find myself trying to place myself back in Hatcher Pass, back in the quiet. But that quiet is populated: by running streams and wind, but it is also noise. Of course, Hatcher Pass has changed over my lifetime … my memory of growing up was a different kind of quiet, it wasn’t overly peopled.” Perhaps the sensory sonorous recollection is best expressed with the Dena’ina word dneldem, a musical sound.

The blueberry bounty and musical sounds of Qughun Betnu have particular resonance which re-echoes with Perea wherever she is. “Food and song travel more easily than people and we need to be as open to the many ways we have always migrated and moved, and food and sound are two ways to think about that,” she says. This is the density of what ‘homegrown’ can mean. The places where we place our feet have their own songs and flavors that we carry with us, in our bodies.

We ingest foods and we become what we eat. Those foods fuel us on a cellular level just as when we hear our bodies are literally moved by the sounds we perceive. When we speak, or make vibrations with our bodies or instruments, those vibrations touch the bodies of others who listen. When we share foods with loved ones, those foods become part of them.

Language practice and food practice offer modalities for bringing into being embodied knowledges, of manifesting what Perea describes as the “multisensory world of eating and singing and touching and all these things.” Speaking, singing, making sound, and harvesting, cooking, and eating are performative. In other words, they do something in the world, such as transmitting knowledge, enacting identities, and realizing ways of being across times and spaces.

Herself in the process of learning Dena’ina, Perea discusses how Indigenous language and song bring things into being. She says, “Speaking these different things is bringing them into being, things that have been asleep… not gone, not dead, they just need to be vitalized… By speaking them again we are literally, actively bringing into these ways of being that… are in the land, in the food, in our bodies intergenerationally.” She adds, “To decolonize oneself is to think about what you put into your body; food is a part of that.” To say the word gega puts it on the tongue, on the body and brings intergenerational ways of knowing into being. To make and share a beloved dish is a culinary act, and also enacts lineages of belonging. “Gega, gega, gega.” It’s the sound and taste, the multisensory feast of buckets, hands, mouths, and hearts full of “berries, berries, berries.”

Perea asserts, “You do have agency in shaping the world you are living in; the revolution starts at home.” Song and food, what we speak and cook, eat and listen to, are part of that multisensory revolution. Importantly, home and the homegrown are not located in a specific geographical sense of place but embodied where you are.