Grounding in Wild Foods

Frost laces the edge of a puddle as I crouch to tie my shoe. I stare at it a moment. Of course, I know winter is on its way. I can smell the cooler air when the wind blows, but I wasn’t expecting any ice quite so early in the season. I shift my small pack as I stand up.

I’m at Glen Alps above Anchorage, checking on the highbush cranberries that I want to harvest, but I’ve veered off the trail to look in on some wild roses. I stumbled on a marvelous patch of them blooming earlier in the summer, and helped myself to some petals (leaving enough for our local pollinators to land on) while making a note to come back in the autumn for some pristine rose hips. They’re small vitamin C-packed powerhouses. I plan to make some into jelly and dry others for deep winter tea when I’m feeling those cold-weather blues.

Mid-September is my favorite time in Alaska. The frantic activity of the summer has ebbed, and there seems to be a collective breath being drawn in as we all change gears for the winter. The day is balanced on the tipping point between light and darkness; the mornings are chilly while the days remain warm and comfortable. Every day brings a new wild shade of yellow and orange to the landscape. Alaska summers push and pull me, but autumns revive me with their move towards quiet.

When I reach the roses, there are signs that some wildlife has been at them, but whether it was birds or moose or bears, I can’t tell. They’re not ready yet—they’re best after a hard frost—but we’re getting close.

The cranberries are harder to keep a secret. I think every Alaskan has a “secret” berry patch they return to every year, but I’m a realist. I live in Anchorage, and my job is demanding enough that I can’t always head out of town to forage and harvest. Most of the places I frequent in the fall are well-trafficked by both animals and people. It’s fine by me. I don’t mind sharing.

Turning the bend on the trail makes the cranberries appear like a theatrical reveal. Riotous scarlet leaves stand out, even in the autumn forest. I inspect them, turning over the pairs of coarsely toothed leaves for the drooping berries underneath. I pop one on my tongue; it’s so sour I laugh with surprise. I leave the rest; they’ll sweeten with the frost too. Further down in a gulley I see what turns out to be wild red currants protected by a wall of devil’s club—late for the season, but a welcome treat. I brave the prickles and walk away with a few cupfuls.

I take my time hiking back to the car, enjoying the musty smell of damp leaves and spruce.

And that’s when I see it. At least, I think I see it. My pulse quickens. Is that… a mushroom? It is. I clamber up a small embankment and go off-trail again, trying not to crush the smaller plants while not losing sight of what I think—what I hope—might be a king bolete.

The alleged bolete (I’m trying not to get my hopes up yet) is about 30 feet off the trail. I’m honestly shocked that I saw it at all. The brush lined up, arrayed itself perfectly as if pointing big cartoon arrows at the bolete, proclaiming “MUSHROOM THIS WAY!”

When you find one, it always feels like a sign from the universe.

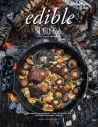

And this specimen is perfection. It’s short and squat, with a rounded, burnt brown cap that a local mycologist whose lecture I attended described as “the platonic ideal of a hamburger bun.” I still can’t get that image out of my head, and it’s the reference I turn to each time I bumble into a bolete. It’s firm— and bless me this day—has almost no sign of insect damage. It weighs a few ounces. I use my knife to cut it down the middle, and the inside is firm but spongy, and a delicious creamy color. I do a private victory dance.

I crouch down and peer around to see if there are more, but if there are, they elude me. That’s alright, I’m already almost stupid with joy over this one mushroom. When I break the tree line, I see the roofs of people’s houses, and I can hear cars. I didn’t leave Anchorage, but for a few moments, it felt like I did. I’m still giddy as I head back, the bolete clutched in my fist. I’m already thinking about how I am going to prepare it. I have a store of some hedgehog mushrooms, and some coho salmon in my freezer.

I cook for a living. Most of what I do, most of what I think about, concerns food and feeding people. There are so many people— chefs and home cooks and outdoor enthusiasts alike—who all know the same as I do: cooking in Alaska means being resourceful. It means being creative about what you have. In my work, I have growers and suppliers who make sure I have the freshest ingredients for my guests. In my personal life, I go to the woods.

But appreciating the wild foods Alaska has to offer—especially in the Anchorage Bowl—is a skill I’ve had to learn, that I am still learning. Our wild foods are often hard to find, and they’re fleeting. Sometimes I feel like other states get off easy. Their wild foods seem so abundant, their seasons longer and warmer. Wild harvesting in Alaska is like a double-edged sword. We have gargantuan devil’s club that will sting you mercilessly if you don’t handle it correctly, but it will also give you incredible medicine if you do. We have sticky poplar, and crabapples, and smelly cow parsnip. We have wild currants, chaga, hedgehog mushrooms, fireweed, an abundance of berries, and—most glorious of all—salmon renowned the world over for its pristine quality and nutrition. But you have to do a lot of research and work to get the most from these foods, even the ones right outside your front door.

As a chef, I have to consider where my ingredients are coming from, and who is growing and harvesting them. With our global environment and global marketplace more fraught and fragile than ever, I find myself looking harder for food closer to home. I’m looking for comfort too. There is a lot of uncertainty about the future, especially for the environment.

Our wild salmon harvests depend on clean, cold water, and protection from overfishing in order to thrive. Hotter summers mean drier forests and more wildfires. Destructive overharvesting affects everything. Every spring when I harvest fiddleheads I’m struck by the knowledge that my gleaning, though small in the scheme of things, could impact the growth of that plant for the next four years if I am irresponsible. The salmon we put on our menus every season is a cornerstone of Alaska food culture. We’re lucky enough to live in a place with access to salmon from places like the Copper River, where sustainable practices support the women and men fishing, and the fish both. It’s a hard balance to strike, so it’s worth celebrating.

Especially now, with the effects of a global pandemic and societal struggles impacting all of us in myriad ways, I find I can ground myself in the present by turning to nature in this way, by being grateful when these ephemeral ingredients land on my table. Through this entire strange year, it’s the best way I’ve learned to tell time, to be in the moment. I store it all up against future need.

I think the best of Alaska’s bounty lies in the work required to get to know it. Alaska doesn’t yield easily. But build a relationship with it, and you’ll be awed by the results. Walk in the park, go into the mountains. Look for fireweed. Look for cranberries. Hunt mushrooms. Cook dinner together. Nourish yourself.

We may have some of these foods forever, and we might not. In the interim, gratitude makes all the difference. We have an awareness of time outside of our planners and our jobs and the 24-hour news cycle. Even with the smallest harvest—a handful of berries or a single bolete—our buckets overflow.

LATE SEASON HARVESTS: Blueberries / Fireweed Blossoms / Chaga / Highbush Cranberries / Lingonberries / Juniper / Rose Hips / Mushrooms (Bolete, Yellowfoot Chanterelle, Hedgehog, Lobster) / Chickweed / Dandelion Root / Coho Salmon

AK Provisions: Alaska Flour Company, Alaska Wild Harvest Birch Syrup, Far North Fungi, Copper River Salmon, Local Farmers Markets

Editors’ Note: Alaska has a bounty of edible plants, and some of them resemble toxic plants. Mushrooms are particularly tricky for beginners to identify. Take care to learn before you harvest. We recommend foraging first with a knowledgeable wild harvester and consulting experts and guidebooks frequently. Check our archives for detailed articles on wild edibles, including roses, fireweed, and mushrooms.