Taking the Sting out of Nettles

“Out of this nettle, danger, we pluck this flower, safety.”

--William Shakespeare, Henry IV, part 1.

I was taken foraging on my first full day in Alaska. Looking back now, it seems obvious and fitting that my introduction to the state would be about the land and its bounty. Picking salmonberries on a roadside, we were standing in the shadow of Cordova’s Mount Eyak, ringed with low clouds. Over the berry bushes and fireweed blossoms, we could see Orca Inlet. A boy rode by on a bicycle with two silvers slung over his shoulder.

Now, living in Juneau nearly nine years later, my year is an almanac of wild edibles. The changing seasons and the growing and fading light are punctuated by tender green shoots, blossoms, berries, and mushrooms.

Nettles mark the start of my foraging year. Depending on the weather and the state of thaw, the first green leaves can appear in Juneau as early as April. Those of us who care about nettles here all seem to share the same generous patch close to the center of town. But there’s no need to be secretive or stingy--this “weed” thrives on being picked.

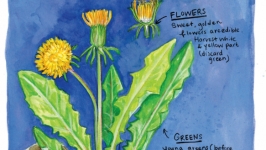

Urtica dioica, or “stinging nettle,” loves disturbed ground. It appears in nearly every part of the northern hemisphere. My favorite spot to find it is in an avalanche chute. Nettles can share turf with salmonberries and fireweed, twisted stalk, and wild violet. The early, tender leaves are the most desirable. Most botanists suggest taking just the top four leaves.

I bring a small pair of scissors, and I wear gloves. Occasionally, or even often, in my spring exuberance, I’ll find myself picking bare-handed. The result for me is a bright, buzzy sensation in my fingers, but some people may react more strongly with rashes and irritation, so do wear gloves when working with nettle.

Nettle is rich in vitamins A, C, D, and E as well as calcium, iron, and potassium. Despite its legendary sting, it is quite edible. Historically, it’s been used to make beer and cheese (it’s a natural rennet), and the stems are used as a strong fiber like flax. The irritant is defeated by drying and by heat--so blanching, steaming, and baking are all suitable preparations. Once I began to see nettles as a nutrient-packed green, it appeared that its uses were endless: stir fries, steaming, lasagne, soups, smoothies, tea. Recently, I met a bartender who makes nettle bitters. She infuses the dried leaves in alcohol, then adds a bittering agent like grapefruit rinds to make wild flavorings for cocktails. It’s on my list to try this spring.

When nettles are in their prime, it’s possible for me to collect too much--not because I don’t have uses for them, but because the cleaning and sorting takes more time than I might have in an evening, and they wilt quickly. So take what you can process in a day, then go back for more.

To prepare nettles, wash them gently and dry in a salad spinner, discard any damaged leaves, and pull the leaves off the stems. To dry them for tea, or for gomashio (see recipe) I leave them on paper towels on a cooling rack, and just let them air-dry for a few days. When they’re completely dried, they can be stored in an airtight container. You'll find recipe ideas in the links below.

---

First published in the Spring 2017 issue of Edible Alaska.