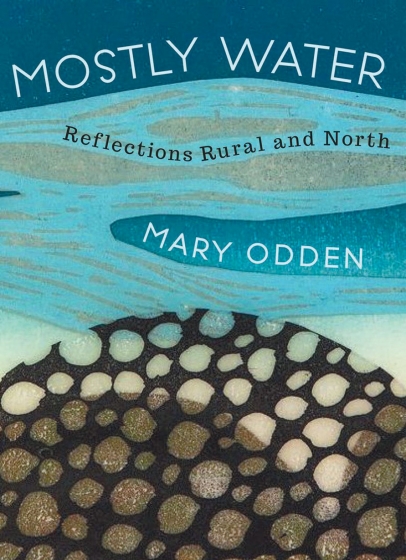

"Recipes" from Mostly Water

Mary Odden’s memoir-in-essays, Mostly Water: Reflections Rural and North, moves from eastern Alaska’s arctic and subarctic river towns. Odden quilts a vivid seldom-seen places, soundtracked with fiddle dances and potluck.” Readers will hear dance music ring through little towns and watch as friends stoke the fires and fading memories of an old pioneer. The danger of childbirth takes a crooked path through a mystical elk hunt on its way to the miracle of holding a child. Casual meetings with passengers on a ferry open to intimacy with a Tlingit grandmother and the dignified depths of an ocean-going hobo. Bush town storefronts forsake their rivers to welcome the airplane. The falling of the Twin Towers on 9/11 silences the sky over a remote Alaskan village.

The essays of Mary Odden’s collection, Mostly Water (Boreal Books / Red Hen Press, June 2020) are punctuated by “recipes”— short takes that converse with the longer essays’ subjects. “Mincemeat” for example, describes an extended family production of an old, sweet food made from wild meat. The “recipe,” while nearly providing actual directions for preparing and eating mincemeat, bridges the distance between “Going to the Hills,” an essay about a horsey eastern Oregon childhood, and “March,” a young woman’s initiation into the Alaska outback’s brightest month.

“Lingonberry Sauce” records the far-reaching harm of Chernobyl and joins the tabula rasa hopes of “March” with an account from later experience: “From the Air,” an essay about a fire-fighting flight across Alaska’s interior that longs to touch down and belong to the land and people below it.

“Seeing the River,” an elegy to old travelers at McGrath, is followed by “Potluck,” which takes a look at a potluck at the McGrath school and the unclassifiable, delicious agutuk in the center of the table.

Edible Alaska hopes you enjoy these excerpts—little “meals” from Mostly Water—and we encourage you to pick up and enjoy the entire book by Mary Odden, writing from Nelchina in Alaska’s Copper River Basin. It’s a well-written, powerful read.

—The Editors

MINCEMEAT

Decide to allow meat to be dessert, but then refuse to eat your own piece after the holiday dinner that features it. The next morning, eat it for breakfast: take the thick slice and warm it in the cookstove oven until it is crisp. Don’t let it anywhere near the microwave or the crust will turn to mush.

To make mincemeat, start with the neck of something wild: venison, elk, caribou, or moose. The neck is stringy and boney, but flavor lives between the muscle and the bone, which makes the neck a place of opportunity. Put the neck in salted water in a big pot and boil it for several hours until the meat comes loose. Take the bones out and discard them. Separate the meat from the broth, keeping both. Let cool. Run the stringy cooked meat through a grinder with twice as many apples as you have meat— some tasty tart kind—and a third as much suet as you have meat. Use a whole orange or lemon for every five pounds or so of meat. Suet is not just fat but kidney fat from inside the animal. Few butchers’ counters think that you know this. If you didn’t save the suet when you butchered, then get fresh real beef suet from a butcher shop. Argue with them if you need to.

Now you are ready to cook the mincemeat, probably in the same large stock pot where you cooked the neck. For every 5 pounds of meat you originally got from the neck, you will need 1½ pints of apple cider vinegar; 1 cup of broth from cooking; 1 cup molasses; 2 cups sugar; ½ cup of butter; 1 tablespoon each of cinnamon, cloves, and nutmeg; ½ tablespoon of mace; and 2 cups of raisins. Combine ground meat-apple-suet mixture with all the other ingredients and start cooking and tasting. The mixture should have a very sweet and sour character.

If you have an Aunt Anna, this is where you throw the recipe away and stop measuring. She and you will keep tasting the mincemeat and move it toward your own ideas of delicious: adding sugar, vinegar, salt, spices, or lemon rind as needed. When you are satisfied, can or freeze the mixture in quarts for pie-making. When assembling a mincemeat pie, slice a fresh apple on top, with a pat of butter, before applying the top crust.

Gather the family. If you grew up eating mincemeat pie at holidays, some of those present will be dead, but they will invite themselves and they will be welcome. Remember that eastern Oregon farm ladies wore those printed aprons that hung around their necks with the strings tied in back and they hardly ever sat down. Remember that the men had waited a long time to eat this pie, coming in from fields that are gone now. Don’t worry if your father pushes his chair back; he’s the one who taught you to save your piece of pie for breakfast. You belong to these people. Set a big table.

LINGONBERRY SAUCE

After Chernobyl, the berries were injured. It happened in the spring, on April 26, 1986, my husband’s thirty-fifth birthday.

Native women in Alaska sent meat, fish, and berries to Laplanders in the fall because during the event, Chernobyl poisoned the ground with radioactive Caesium-137, a water-soluble isotope that plants and animals take up like salt. The people closest to the Chernobyl reactor and all the people downwind of the shifting plumes being emitted by the ruined power plant could not safely subsist off the land.

Lingonberries are lowbush cranberries that grow in forests all over the top of the world. The Kobuk Inupiat call them kikminak, and women’s hands stroke them from the hillside into deep birchbark baskets. Finlanders call them puolukka. In eastern Canada they are foxberries or redberries. In Norway and Denmark they are tyttebaer, and the Swedes gave their lingon name to us. They are in the genus Vaccinium with blueberries, which their stems often touch, but when blueberries are soft and shriveled and their red leaves have vanished in the fall winds, the lingonberries are ready to pick and their tiny, waxy oval leaves will be green under the snow all winter.

In the summer, we watch the clouds of Russian forest fire smoke drift over our short forests, until the wind shifts and we send them our Alaskan smoke, waiting for the smoke from Canada’s Yukon to drift in from the east. The world is small at its top, the center of a spinning disk.

Pick the berries after one or two frosts, after they are red all over but before too many frosts have softened them. Pick bucketfuls. Pour your berries from one bucket to the other in a stiff wind or while your friend flaps a big piece of cardboard to blow away sticks and leaves. The berries will sound like hard rain as they fall on each other, filling your bucket with red opaque jewels. They will keep all winter in a cool room; use them by the handful when you need them or make a sauce for meat. You can eat the sauce on bread, too, or stir it into pudding. Morrie Secondchief told Norman to eat a spoonful every day to stay healthy. To eat lingonberries is to taste the bright sour heart of spruce and poplar woods in the late fall, when the winds that blow across the north have turned cold and the ground is waiting for snow.

I am comforted to know that wind does not belong to anyone. The mercy we could give the forest is for ourselves. Beauty and danger and comfort are human things, and they will not outlive us.

POTLUCK

It’s better when you don’t have to sign up. Wild chance and how different we all are anyway brings main dishes and vegetables and noodles and breads and desserts. Someone has brought just moose ribs, cooked for hours, with only the magic of boiling water to separate and suspend the textures and flavors of muscle and sweet fat. In that pot, nearly empty already with half the line of people still eager to dip into it, vegetables would have been an unwelcome distraction. All the cartilage between the bones is cooked to delicious jelly. Don’t leave those ribs in the woods. Don’t waste: ribs are the best part.

How good it is to eat what other people bring: food I could not think of, food I don’t have any left of in the freezer, food from another culture. Agutuk (Ah-goo’-tuk) is usually there on the long table. It is never exactly the same, even from the same house and hands. The berries are different this year, or there is no seal oil, or it is a different white fish. Sometimes it’s made with what people here often call salmonberries. These are not the salmonberries from down around the coast but the quiet ones hard to find and farther inland, just one on each little stem. The Scandinavians call them moltebaer, and in plant books they are cloudberry.

Most often, agutuk is made with blueberries, my favorite, especially when they are mixed with white fish—cooked and pulled apart then smushed to a latticed texture on your tongue—and with seal oil if the cook has it, brought by some cousin nearer the coast.

Sometimes the cook uses Crisco instead of kidney fat or that lace from around a moose or caribou gut. Crisco, fluffy and white and odd, but an old friend in the villages—a canned and stable fat, a familiar, and if you think about it, no weirder than the white stuff on wedding cakes.

Always sugar though, that old treasure.

We call agutuk by its Inupiaq name, even though an Athabaskan grandmother brought it. She knows how to call it in her language, but this is easier and everyone who loves this place loves to say it. “Eskimo ice cream” is for people who might start looking for eskimaux. Ordinary and precious, agutuk is there in the middle of the table with the ribs and meatballs, hardly ever with the cakes and cookies at the end. It is not a dessert but a hope and a surprise so it defies categories. Someone is generous with her berries and her idea of who we all are. There’s a big spoonful in each paper cup, just enough cups to go around.

Excerpts published with permission of the author and Boreal Books / Red Hen Press.