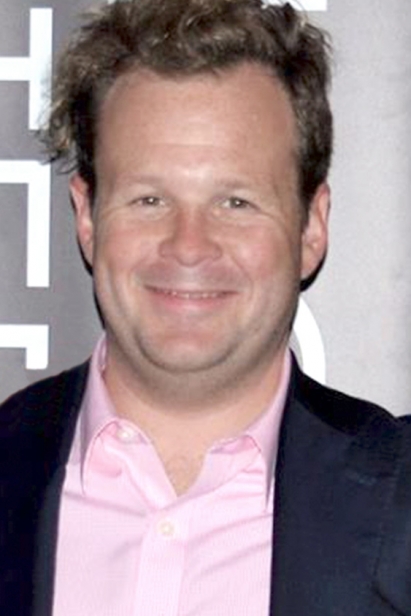

DISH with Jack C. Newell of 42 Grams

The best food film I've seen lately isn't exactly a food film. It's a film about food people.

Director Jack C. Newell’s newest film 42 Grams is a portrait of Chicago chef Jake Bickelhaupt. With the help of his wife Alexa, a dedicated and integral character in her own right, Jake turns a pop-up restaurant in their apartment into a foodie hotspot.

A year later, they turn an abandoned chicken joint into a real restaurant by the name of 42 Grams. We follow them as they develop menus, hire and fire staff, and sacrifice it all for their dream.

Newell brought the film to the Anchorage International Film Festival (AIFF) in December 2017, where I saw it in an intimate house screening. Following the festival, 42 Grams was selected for the annual Best of Fest showcase, a series of free weekly screenings of critic and audience favorites.

Ahead of the film's screening on Feb. 6, I reached out to Newell to talk about the film and find out why he calls it the “ultimate foodie anti-foodie” movie.

Click below to listen to the interview with director Jack C. Newell.

I was excited to hear that your film was going to be included in the Best of Fest series.

Yeah, that’s awesome. It’s a good honor. It’s nice that more people get a chance to see it.

There are no shortages of stunning food documentaries these days, especially with the rise and popularity of Netflix’s Chef’s Table. What made you want to make this film?

It’s kind of interesting because when I started making this film the whole food, chef documentary thing wasn’t a thing. Not saying I invented chef documentaries, but it wasn’t this known thing, it wasn’t a genre unto itself. So much so that, the working title for this film for a while was The Chef’s Table. And then Netflix came out with this thing called Chef’s Table and I was like, “Well, what the heck?!” You know, they stole my title. I was so angry when that dropped because we had been filming for like a year and a half by then. But I didn’t have the film done, and they stole the great title. But we ended up with a great title, 42 Grams, which is an amazing title. So you know everything happens for a reason, I guess.

So to answer your question, I didn’t go in thinking I was making a food documentary. I had made another film called Open Tables, which took place in all the restaurants in Chicago and Paris, France. So I thought I had known the food scene and when I found out there was this underground restaurant I was taken aback. I was like, “I know all of the restaurants. What is this restaurant doing that I haven’t heard of yet?” … I was absolutely blown away by the quality of food coming out of Jake’s kitchen. And it wasn’t like an industrial kitchen at a fancy restaurant with a million-dollar build out, it was his apartment. And I was like, “There’s something here.” This is just interesting. This guy is making what I would consider Michelin-level food out of an apartment.

I want to talk about the characters a little bit. Jake is this aggressive personality which helps him get to his end goal and it seems like Alexa is along for the ride with us. Can you talk about what it was like getting to know them and being on this rollercoaster with them?

Oh yeah. He’s got this dream and it’s fairly simple, but the film opens up. I don’t want to use a food analogy because that’s lame, but it’s almost like an onion with the layers coming off. As the film goes on, the pretense drops away more and more until the end when it’s at its core. And the core is not necessarily all good. It’s actually very emotional and it’s comprised of a lot of different things — both good and bad. Obsession and ambition, you know, the flip sides of the same coin. Intense pain, but also intense happiness.

One of the things I like about the film and what we’re trying to do in the film is to create a very full portrait of these people on this ride or in this experience. So the film is both silly and serious, intellectual and whimsical, funny and sad. It’s hitting a lot of different things because I wanted to try to give the audience essentially their experience to make them feel like they’re with [Jake and Alexa]. One of the things that I think we’re successful in is that … people always come up to me afterwards and they feel like they were the third person in that room with them. They feel like they are in the trenches with them, which I think is really exciting and I think one of the things a documentary can do really well.

I was really blown away by how you depicted the characters. Even in other documentaries, people can seem two-dimensional, so I was really impressed with that in your film.

I agree. [ I had ] no interest in making a commercial for them for the restaurant and I will give them credit absolutely because it was very important to them that we told the story right and go to those dark places and really allow their warts and all to be there.

Both Alexa and Jake know exactly who they are. They have no illusions about who they are, I don’t think, and they deserve a lot of the credit to go there and open up and to understand that what they’re saying is on camera for all time. And that’s cool and I think it is one of the things that makes it special.

I want to talk about how you address Jake’s alcoholism in the film. At the time of filming, Sean Brock and other people in the food industry weren’t really talking about mental health and addiction openly. Why did you feel it was important to include that and did you waiver on that decision?

No, never. The only thing we did was we had a cut of the film where it wasn’t explored as much and we went harder. For me, all of the alcoholism and the stuff at the end where they talk about the true costs of what they sacrificed to get what they want, it was really about how much does it need. And I went with a less is more approach, just enough to hint at it. I didn’t want to make a movie that was like showing him overcoming his alcoholism because he gets validation from being a chef because that’s bull––. I didn’t want to do that because that’s not how life is, you know, life doesn’t work like that.

I remember filming that day when Jake is cleaning the countertop and he’s talking about how he’s having trouble with chefs. I didn’t know he’d gone to AA and I didn’t know he’d had realizations about his own drinking, although I had kind of figured that he had issues with drinking. When he did that on camera, I was like, “OK, wow, we’re going there.” And that was good, you know?

It was never even a question were we going to put it in. I think the answer was always yes … We’ve had other chefs who’ve seen it as well. Every chef or any person who’s been in the restaurant world who’s watched this film has said that’s right on, you hit the nail on the head. That’s the best compliment I could be asking for. We told something that’s true, true to their experience.

… It’s a fairly common thing in the restaurant world [ to ] have substance abuse and drinking problems. This film isn’t going to be like, “Well, now they’re all better.” … My aim going in isn’t to make a commercial for this restaurant and it isn’t to glorify or deify these people, it’s a portrait of an artist. My idea going in was that I wanted to show this artist and his process. I’d approach it the same way if it was a painter or an architect or a sculptor or a dancer or whatever. His mode of expression is food. He’s an artist. We wouldn’t shy away in any of those other things and I wouldn’t shy away here as well.

Now the industry, because of Sean Brock and all of these other folks, it’s getting more attention now. I think that’s good. I have no idea how the whole thing is going to play out industry-wide, but I think more talking about it probably the first step in the right direction.

You consider Jake as an artist. Before they were viewed as servants in the back and kitchens were closed off. Now we’re seeing restaurants that are open concept. Why do you think our idea of a chef is changing in that way?

Well, it might be a fad right now — the walls are coming down and all that stuff — but who knows in five or 10 years, it might go back. It might be cyclical. When Jake was doing it and the level Jake’s doing it at, he’s relatively at the beginning or the vanguard of all of this. I think it’s definitely more and more common, but even so much as two to three or four years ago it was less common.

There’s a moment in the movie where Jake says he was working in these restaurants and he realized he wasn’t ever going to be executive chef there, so he quite and he went back to school. I ask him, “So what’d you go for?” And he said physical therapy ... Jake is clearly a chef ... He’s so clearly a chef. It’s almost unbelievable to think that he would have ever gone a different path … How I experience the world is through storytelling and filmmaking and I think Jake is the exact same way. It’s how he experiences the world. It’s how he processes everything that comes to him. It’s how he expresses himself.

There’s a sequence of research and development that is a side that we don’t get to see in these other films or portrayals of chefs in their restaurants. We don’t get to see that creative process that you were talking about.

No, you don’t and it’s really unfortunate. And I think there’s a lot of reasons why. The creative process is inherently messy and is difficult to turn into a narrative and that’s just true. I think when you see it in these other chef movies ... it ends up feeling like a cooking show, and that’s fine ... but it’s not really what we were going for there.

And that goes back to the I was saying before, that I don’t consider this necessarily a food movie. I call it the ultimate foodie anti-foodie movie. It’s going to give you everything you want in a food documentary, it’s going to hit all those things, but it goes in other more interesting spots.

You have said that this film shows the cost of ambition, obsession, and the American Dream. What do you think the American Dream is and how does that play out in this film?

The American Dream is probably a constantly changing thing, but the way I see it right now is that if you work hard and put yourself into it, you’ll get it, you’ll get made, you’ll make it. I think that’s widely accepted that’s what the American Dream is and I think this film is that exactly.

These are two people who have a dream and they literally put everything into it. All of their time. They sacrifice their marriage, they sacrifice relationships, they put in all of their life savings to realize a dream. And they get it.

But the reason it’s about the true costs is because it’s more complicated than that unfortunately. The American Dream is an ideal that we’re all striving for but the idea was to try and explore what are the true costs of that. The reality is that there is just no — it’s essentially the equivalent that there’s no such thing as a free lunch — but there’s just no clean wins. It’s very difficult to do anything and come out unscathed on the other side… This doesn’t mean then don’t try or you shouldn’t try and do anything. I’m just trying to paint more of a full picture of this as the cost...

As the artist, that’s my contribution on us as who we are … I’m in a very privileged position because as an artist and a filmmaker you don’t have to have all the answers, you just have to ask the questions. My idea is to get people asking these questions. I’m curious if it has a larger conversation in the food scene around this film because of what we’re seeing, kind of the carnage and the collateral damage for all of this.

What made you want to bring this film to Anchorage and AIFF?

I had heard for years that Anchorage International was a good festival, just through the grapevine — good program and a good community of people who like film. So you want to get into the good ones, obviously. There’s definitely a lot of them out there that are good, but I had heard that with Anchorage there are good audiences, they treat you well [ and ] I had wanted to go to Alaska.

When we were there it was really cold, but beautiful. Stunningly beautiful. And the food scene in Anchorage was great. I had a lot of great food from a number of different places there. There’s no reason why there shouldn’t be good food in Anchorage. I’m not trying to back-hand compliment. It was great. I went to that breakfast place — what’s the name of that breakfast place that everyone goes to?

Snow City?

Yeah, Snow City was fantastic. There was a hot dog cart like two doors down from that that was really good actually. So everywhere we went the food was great. It’s like clearly people in Anchorage have a love of good food. A movie like this we want to show in any place that has a food scene and people who like and care about food.

When you were here for AIFF, they arranged a house screening of your film. Had you done anything like that before?

Yeah, so we did it at Anchorage Community House and it was great. What a filmmaker wants when they are showing their film is a crowd and that can sound like they want a lot of people but sometimes you just want the right people to watch your film.

So when [ AIFF said ] we have this idea to do this intimate screening at this house and have a chef cook food and it’s kind of small. It’s almost like going over to a friend’s house and watching a movie. I was like, “Yeah, that’s amazing.” Especially because of the Sous Rising thing. But absolutely I said yes to that.

With Open Tables because that also takes place in the food world and this film, we’ve done things like this before. Jake says it in the film, and I believe it to be true, that we get really wrapped up — and I just spent the last 25 minutes talking about food — but we get really wrapped up talking about the food, but in the end it’s just a reason to bring people together.

It’s about the fellowship of sharing this with someone else. And showing a movie in the theater is obviously where we intend to show it, but I think most people nowadays interact with films in their living room or on their computer, so I think it’s a great way to screen it and great way to experience the film. I hope more people do more screenings where they invite people over, make a meal, and watch the film. That would be a dream come true.

42 Grams and Open Tables are available on iTunes, Amazon and Vimeo. 42 Grams is also now available on Netflix.

Come see it in person! Join Edible Alaska for a free screening of 42 Grams at the 49th State Brewing Company in Anchorage on Tuesday, Feb. 6 at 6 p.m. A panel discussion featuring local food personalities will follow the film. This event is presented in partnership with the Anchorage International Film Festival.

Jessica Stugelmayer is the senior digital content editor for Edible Alaska. She can be reached via email, Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.

Some questions in this interview have been edited for space and clarity.