Basic and Primal

Remembering the Food, Drink, and Revelry of Eastchester Flats

Editors’ Note: Culinaria Obscura connects contemporary foodways in Alaska to their histories and contexts, drawing on archival materials, historical documents, and the voices of community experts who have gathered deep knowledge through experience. We welcome a pair of guest writers for this issue’s Culinaria Obscura story, developed in partnership with the column’s usual author, S. Hollis Mickey

In 1958, Fred Johnson, a young Air Force Navigator, arrived in Anchorage. On the eve of statehood, Johnson found Alaska more welcoming to Black men like himself than his home state of Illinois. But he also noticed that not many other Black people lived in the territory. So naturally, Johnson was surprised and enthusiastic when he noticed a few other Black folks at the Anchorage Park Strip playing baseball on a neighborhood team.

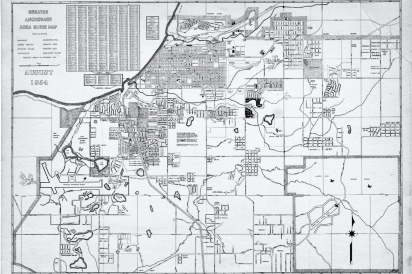

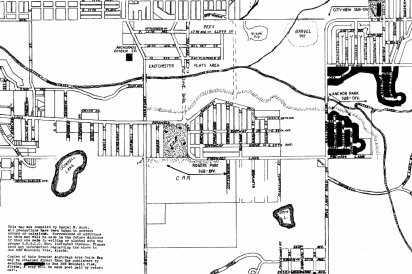

After introducing himself and making friends, he was led by the players to Eastchester Flats, a predominantly Black community located along the north banks of Chester Creek in an area today that exists as a greenbelt and the Seward Highway corridor that connects downtown to midtown. What is left of Eastchester Flats has been absorbed into the Fairview neighborhood. However, for a time in the 1950s and early ‘60s, it was the nation’s northernmost Black community and housed the largest cluster of Black-owned businesses in Alaska.

Due in large part to housing discrimination throughout Anchorage, Blacks settled in and around Eastchester Flats by necessity; it was one of the few places to buy or rent a place to live. As one resident, Madeline Holmes Hendricks, recalled in Alaskan Blacks Salute the Bicentennial, “When I came back here in 1950, I went to every real estate dealer in town trying to buy a house… Not any would sell me any property. They all referred me to Eastchester Flats.”

Despite this racism, Black communities nonetheless endured and found creative ways to thrive on the margins of white society. As for Fred Johnson, he took well to Anchorage and decided to make Alaska his home after completing his service in the military. He began work in The Flats, as it was widely called, first as a bartender and then as a business owner. Johnson remembers his time at the North Star Light Lounge, established by Jesse LeRoy Hayden. Unlike many of the businesses in the Flats, the North Star Light Lounge had a territorial liquor license. Its clientele came looking for a good time.

Although the area was primarily inhabited by Blacks and transient workers who came through Alaska for one reason or another, the businesses of Eastchester Flats catered to a diverse crowd looking to blow off steam in a part of town generally free of law enforcement. In fact, throughout the 1950s the Flats was not technically within the boundaries of Anchorage and thus existed beyond the jurisdiction of its police department. “It was no police” in the Flats, recalled Joe Jackson, who documented the freewheeling nature of the community.

The makeshift clubs and lounges served liquor and beer; some contained small dining rooms equipped with modest kitchens to serve food. The North Star Light Lounge, like the other bars in the area, opened around 8 am and served liquor until 5 am. Between 5 am and 8 am, the lounge often remained open for breakfast. Johnson recalled that they also served lunch but never dinner. Beyond the North Star Light Lounge, there were also the Backstreet Club, the Red Hut, and several short-lived businesses; many of these were illicit, but others were straightforward clubs, bars, or restaurants. The Flats came to be viewed as a “colored quarter organized by and for colored people,” according to Herbert Frisby, a Black journalist who spent significant time in Alaska. “We were a small city within our own selves,” reflected Joe Jackson, a resident through the 1950s.

Bar owner Zelmer Lawrence recalled: “You could go to the Flats and find things you couldn’t find any other place in the state… At one time there were any number of cocktail bars running full blast in the Flats. You could get Schenley’s [a Canadian whiskey], you could get the finest vodkas and wines and everything, no liquor licenses. There must have been 20 to 30 of them. Just a no-man’s land.” According to Jackson, “It was shacks all over the place, and it was prostitution and gambling, and everyone that was down there had some kind of a what they call a club.”

Johnson recalls serving drinks at the North Star Light Lounge. Most patrons ordered “basic and primal drinks,” he recounted. Jack Daniels and Coke or Hennessey on the rocks were popular choices. The goal was to have a good time and leave your troubles behind. Dancing and live performances lit up the lounge for nights of easyto- sip libations and entertainment. Some of the more notable acts included bluesmen like T-Bone Walker and Jimmy Rushing, as well as the performance artist, LaWanda Page.

Jackson relayed a conversation with Anchorage’s chief of police who estimated the illicit businesses in Eastchester Flats brought in over $3 million throughout the 1950s. Ben Humphries, a longtime labor and civil rights activist, remembered the scene in similar terms: “there were a lot of clubs, where, if you wanted to find the real action, you went to… Eastchester Flats... there was more fun there than you’d find anywhere else. Action happened there.”

After a night on the town, denizens of the Flats may have decided to venture up the road to the Fairview neighborhood to eat at the Broken Mirror or the Nevada Bar and Restaurant for southern cooking, a term more recently defined as “soul food.” The Broken Mirror, located on 13th Avenue, employed a Black cook whom Johnson knew as Ms. Willy. She baked little pies that had the reputation for being the best in town. Johnson recalled both the sweet potato and lemon meringue. Others ate at the Nevada, a white-owned restaurant with a largely Black workforce and a diverse clientele.

By the late 1960s, the Flats was targeted for demolition as part of Anchorage’s so-called urban redevelopment or renewal. Though many of the building structures were ramshackle and identified as “blight,” they nonetheless composed a dynamic community within the Anchorage bowl. The loss of Eastchester Flats, which hosted Alaska’s only concentration of Black-owned businesses, marked a turning point in the history of Anchorage and the new state. Other districts, like Spenard, would emerge as notorious for their nightspots, bars, and entertainment. They lacked the diversity and concentrated dynamism of the Flats, though. From southern cooking to northern juke joints, the Flats buzzed with activity for several years in Anchorage’s bustling post-war era. Although the community is now gone, its largely untold history reveals the complexities that underlie housing and hospitality in Anchorage today.

SOURCES:

Author interview with Fred Johnson, September 3, 2020.

Alaskan Blacks Salute the Bicentennial.

Joe Jackson and Ben Humphries, interview, c. 1984, in Oral HX, Blacks in Alaska (n.p.: SKB/Prod, c. 1984). Archives and Special Collections, Consortium Library, University of Alaska Anchorage.

Herbert Frisby, “Tootsie Forgets Her Race in Alaska,” Baltimore Afro-American, September 15, 1951, 15.

Joe Jackson, interview by Bruce Melzer, c. 1982—1983, Bruce Melzer oral history interviews, Archives and Special Collections, Consortium Library, University of Alaska Anchorage.

Zelmer Lawrence, interview by Bruce Melzer, c. 1982—1983, Bruce Melzer oral history interviews, Archives and Special Collections, Consortium Library, University of Alaska Anchorage.