Meet Ruth Allman - Alaskan Sourdough Specialist

I was first introduced to Ruth Allman, Alaska sourdough expert, in a Walmart.

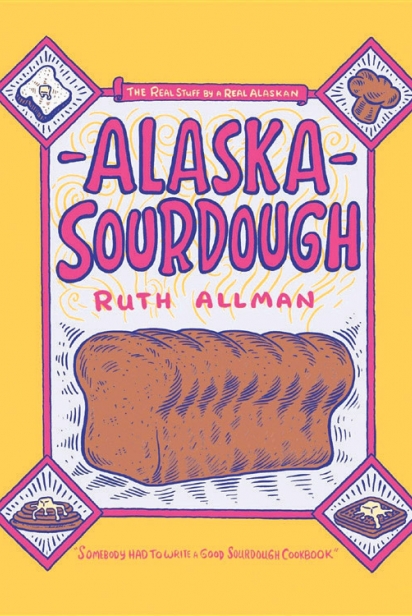

I can’t say I’m especially proud or ashamed of this fact, (and actually, Ms. Allman passed away in late September of 1989, 4 years before Walmart expanded into Alaska). We had just moved to the 49th state and I was in need of some last minute Christmas gifts. The tangerine cover of Alaska Sourdough caught my eye, and instead of sending it to a friend, as planned, I ended up keeping it for myself. Ruth and my introduction, one-sided as it was, seemed meant to be. Or so believes every literary fan of a beloved author.

Alaska Sourdough, first published in 1976, remains one of the bestselling books about Alaska, written by an Alaskan. You’ll find it in Walmart and on Amazon, yes, but also in many, if not most, area tourist and museum shops. Ruth’s Alaskan hotcakes, or “the hairychested cousin of crepes Suzette,” as she calls them, have been featured in Outside magazine and countless other print and digital publications over the past forty years.

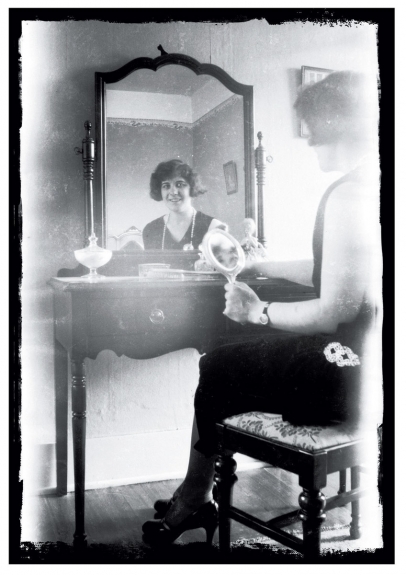

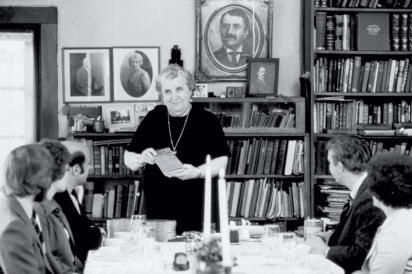

In Juneau, prior to the book’s publication, Ruth Coffin (later Allman) was already a household name. Niece of territorial judge James Wickersham, who had a hand in nearly every policy that shaped Alaska during the first half of the 20th century, it is Ruth who is most credited with preserving and sharing his invaluable historical narrative as it was passed down to her. She also shared her own experience of life on the Alaska frontier. In both accounts, sourdough played an essential and celebrated role.

At the time I first encountered her cookbook, I was already a sourdough enthusiast. I had made my first “starter” — the literal “sour dough,” or fermenting, living, natural yeast-filled goo that you “feed” regularly to give rise to your baked goods — a few years earlier, and brought it with me to Alaska. So when I noticed right away that Ruth routinely capitalized the word “Sourdough” in her stories and recipes, describing it as a “magic food,” a “miracle worker,” and a “protein dynamo!” I knew I was in good hands (fermentation nerds, unite!).

Yet for all of her Alaskan pride and zealous descriptions, she notes that sourdough, or “levain” (natural leavener) is historically an international pioneer food, not unique or original to Alaskan pioneers by any stretch. However, as Ruth points out, what does make Alaska sourdough unique, and has contributed to its becoming such a hallmark of Alaska history and culture, is the great degree to which it was relied upon for survival.

Ruth grew up with her aunt and uncle, and was a teacher in Juneau in the 1930s, but it was when she married Jack Allman in 1946 and moved to the more remote Excursion Bay that she got to experience frontier life in earnest. There, where supplies and transportation were limited, she understood the appeal of a rising agent that was affordable and easy to transport and store in the cold — and could be regenerated with flour and water alone. Her husband Jack, a travelled and tested frontiersman, “was an expert [in using sourdough] and a patient teacher,” she writes, “He had many years of experience using sourdough, and was a great admirer of its qualities. He had become dependent on it and it had become a way of life for him.”

She notes that there were no sourdough cookbooks back then, and recipes, often passed down orally, varied widely between individuals. No one thought to put together a cookbook, it seems, because one’s sourdough, and methods of using it, constituted a revered, personal ritual of sorts. Like the way you make your own coffee or scrambled eggs.

Alaska Sourdough is a quick, surprisingly fun read, full of hilarious sayings and anecdotes about pioneering life. Anyone who has read it (and yes, you will quickly find yourself engrossed in Ruth’s neat, loopy scrawl. Did I mention the entire book is hand written?) can tell you that it’s not because it is meticulously organized, exhaustive, and full of beautiful photographs in the manner of modern cookbooks. Admittedly, while several of the excellent recipes remain in steady rotation in our kitchen, the measurements and instructions sometimes require a little creative interpretation. Instead, its charm, and what sets it apart from other folksy cookbooks of the time, lies in the way Ruth invites us so warmly and viscerally into her cabin kitchen. A talented historian, she not only connects us to a unique time and culinary tradition, but manages to articulate that sense of the pioneering, frontier spirit embedded in Alaska culture today.

Reading about and using “the real stuff by a real Alaskan” (as asserted on the cookbook cover) still makes me feel like a “real Alaskan”, even if an amateur one. As Robert Farrar Capon reflects in his cookbook Supper of the Lamb, “The world may or may not need another cookbook, but it needs all the lovers [and] amateurs it can get.” So let us raise a be-syruped fork to amateur and enthusiastic home cooks; to written words, with their living, regenerative qualities; and to a great Alaskan, Ruth Allman, forever immortalized and ready to acquaint and reacquaint us with Alaska sourdough.

> You can learn more about Ruth by visiting the House of Wickersham in Juneau, Alaska, where Ruth’s family’s heritage is preserved and shared with the public.