30 Days of Muktuk

Josh Ahsoak ate muktuk every day for a month, lost weight, and connected to his culture

The 30-day whale diet started as a joke. It was Christmastime 2016 and Josh Ahsoak’s sister, AnnaFlora, was visiting him in Anchorage. She was doing a 30-day CrossFit diet and was trying to get him to join her. Ahsoak wasn’t sold on her regimen, but it did make him think.

“I had a bunch of life stuff I was dealing with, including trying to get my health and my weight under control,” he said.

Ahsoak, 38, is an Anchorage-based attorney by education. By avocation, he’s a hunter. Ahsoak is Inupiat, with roots in Barrow, where he is on his family’s whaling crew. He travels frequently in the state and estimates he spends about a third of the year subsistence hunting and fishing.

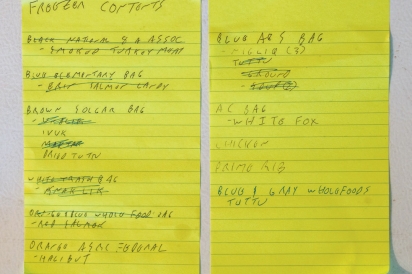

As his sister listed her new dietary restrictions, his thoughts turned to his freezer and the array of wild food inside: fish, birds, seal, walrus, bowhead. “At any given time, I will have anywhere between 50 and 500 pounds of just incredibly good meat and fish on hand from all the hunting and fishing activities,” he said. What would happen, he wondered, if he switched to a traditional Alaska Native diet for a month?

A northern indigenous diet is centered on marine mammal protein and plants. What if he focused on the freezer and avoided eating out or eating processed foods?

Ahsoak settled on whale meat, or muktuk, as the main protein in his diet. He had plenty from a successful spring hunt in Barrow. Whale is high in vitamins D and C, low carbohydrate and nutrient dense. Hunters eat it before going out because it is said to give them energy and keep them warmer. Ahsoak used to eat it in law school before taking long exams because, he said, it kept him from getting hungry. “It takes your body so long to digest it, it’s kind of like the opposite of some kind of empty carb or empty sugar,” he said. “You don’t eat a lot, that’s the biggest thing, it’s very filling.”

And so it began. His sister did her diet, and he ate about 8 to 10 ounces of whale daily. Usually at lunch with a salad. He also added it to fried rice and made it into spring rolls. He exercised moderately. Soon he quit feeling hungry for breakfast. At night, he ate only a snack. “I would have to remind myself to eat at like 7 or 8,” he said.

Ahsoak chronicled his meals on Facebook like someone on a trendy diet, using the hashtag #30daymaktakchallenge. By the end of the month, he’d lost 17 pounds. “I felt much better physically and emotionally when I was eating well,” he said.

Gary Ferguson, chief executive officer at the Rural Alaska Community Action Program, Inc. (RurAL CAP) and a naturopathic doctor who has long been involved with nutrition in Alaska Native communities, said Ahsoak’s experience fits with what doctors know about traditional diets and the metabolic hardwiring of some Alaska Natives. Alaska Natives, who historically did not eat sugar or refined carbohydrates, have a higher chance of having a genetic propensity toward difficulties digesting those foods, he said. “I find that folks who eat a more traditional diet — healthy proteins, healthy fats and less grains and processed carbohydrates — they do better,” he said.

Traditional diets are associated with lower blood sugar levels and reduced risk for cardiovascular disease, he said. Proteins take longer to digest and fats make people feel sated. “I think we need to talk more about this,” Ferguson said. “There aren’t that many in the younger generation going to a traditional diet and saying ‘how does this food make me feel? What does it do to my metabolism?’”

For Alaska Native people living in the urban world without as much access to traditional foods, trying to eat a diet high in proteins like fish and good fats like olive oil, and low in sugars and carbs can be really beneficial, he said. “Even at restaurants, start thinking through the eyes of our ancestors, order the types of food they ate,” he said.

His month-long eating experience also made Ahsoak reflect on the cultural value of subsistence, he said. He lived in Barrow until he was 6, and then moved to Michigan with his mother. He didn’t return to the village until he was 19. “There was a lot of things I kind of had to catch up on,” he said.

He recalled a hunt with his father when he first came back to the village. They went on foot looking for birds and shot as many as they could carry, he said. “I remember thinking, okay, we’re not going to have to go hunting for a while, this is enough,” he said.

He figured they would fill their own freezers, but then they returned to the village and he saw that his dad wasn’t thinking that way. “We went back to my grandfather’s house and he stuck his head in the door and held up a duck and my grandfather was sitting on the couch. He looked up, nodded…” he said. “We went in just a concentric circle out from there to relatives and elderly and we got maybe three blocks ‘til we got to the one extra duck that we kept at home.”

And that was when he understood the dramatic difference between hunting culture and subsistence, he said. Hunters hunt for themselves. “Subsistence means you are hunting for a community,” he said.

When he’s prepping up subsistence foods like salmon, he often posts pictures on Facebook. Friends from out of state will ask if they can buy some. “I have to explain that I’m not opposed to the idea of sending you salmon, but culturally, I can’t [sell] it,” he said. “I’ll get bagels and things from people in New York and I’ll send them salmon and that’s how it works.”

Or he just sends them salmon. Subsistence isn’t about reciprocity, he said.

Recently he was in New York and got to thinking about the hipster trend of elevating old-fashioned objects and foods, glorifying the wearing of flannel, making axes into wall art, calling a jar of pickles “artisan.” “There is this searching for authenticity, even if it is your damn pickle next to your white bread sandwich,” he said.

Whatever it is that those people seem to be looking for, he said, Alaska has it naturally, when it comes to abundant wild foods. With whale, a whole community comes together to harvest, and values it as part of a system that allows people to live in the Arctic. Unlike something processed on a store shelf, it’s a food rooted in a value system and a place.

“Unless you’re being deliberate about it, it’s easy to fall into a life where you’re not eating anything that’s been made with any care... You become divorced from your food,” he said. “When I hold a fish in my hand and gill it and gut it and put in the box, I’m getting as close as I can to the food. I can say I know where this fish came from because I took it out of the water. I think that’s the definition of authenticity.”