Apron On

Musings on Making

We don’t have much information about this apron or its context, but I think of it as a record of sorts—a garment that holds stories of work and wear and life from someone who came to Alaska over a century ago. Held in the Anchorage Museum collections, its slim object file holds an accession record typed (and hand corrected) on yellowed paper showing it was gifted by Betty Jo Staser to the museum in 1979 along with a handful of other objects. The record notes that the translucent, cotton apron is in fair condition, discolored, with some stains, tears, and signs of use, and that it belonged to Agnes Thies, who moved to Alaska in 1890 and served as postmistress and laundress of the mining town Cleary. The record says she was also known as Bedrock Annie by miners who paid for her services after they hit gold.

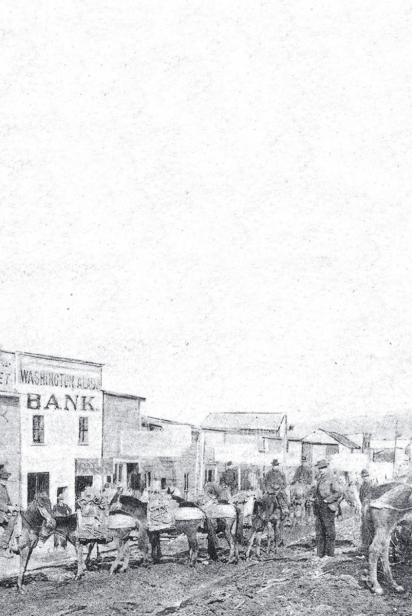

Mining in Cleary Creek began as early as 1903. From 1903 through 1924, it produced about 1,129,650 fine ounces of gold, with the largest nugget weighing 13.51 ounces. Plenty of data exist about the mining output of Cleary over the years, but information about Agnes Thies is scarce. Old copies of the Fairbanks News Miner reveal her marriage to Walter Skof in 1912, an apparent court case between the couple and Jack King of unknown litigation, her passing in 1937 at age 67, and execution of her will in 1938. I wonder about the details of her life between these recorded points.

In 2016, when I moved to Alaska, I brought just a few bins of clothes and a blue chair. I wanted to be able to see out of the back of my Honda CRV on the trip from Providence, Rhode Island, the lands of the Narragansett and Wampanoag, to Anchorage, the homelands of the Dena’ina. One of the items I judiciously packed was a Heritage canvas apron. I have worn this brand of apron for years in both my art studio and kitchen. It is a sturdy workhorse of an apron: deep, wide pockets, thick strings that wrap twice around my body. Tying on my apron signals that I am at work, creating something to share with others. An apron is my uniform identifying my role as maker: artist and cook.

My $15 canvas apron is not particularly special or irreplaceable, so why did I select this garment to migrate with me across the country? It is covered in memories: elaborate art projects in the dirtied pockets, dribbles on the bib from tasting spoonfuls mid prep, and burn marks. My apron is a record of art and cooking, a record of what I have done that makes me who I am always and already becoming.

The word apron derives from the Old French naperon, a diminutive that means “small tablecloth.” The apron is a kind of tablecloth for the body, guarding clothes and person from wear. Workwear has been around as long as clothed humans have worked. Apron-style garments may indeed have been some of the earliest clothes worn, both for practical and ceremonial purposes. Indeed, throughout the centuries of wear, the apron has been used not only to signal labor, but also to signal tradition, status, and fashion.

When I look at Agnes Thies’ apron, I ponder what the garment might tell us about Agnes: her hands washing clothes, posting miners’ letters home, her hours lived gold strike to gold strike. The thin cotton looks fragile, but the apron is made of dimity. Dimity is lightweight and sheer, but woven to be a quite durable fabric. Did Agnes wear it for her duties as postmistress or while doing laundry? Did she wear it at home, in her kitchen, for tending her own hearth, cooking, or other house work? Or, was it donned for special occasions, after most of the hard work was done? The apron has just a few holes, a few stains. But dimity washes well; perhaps traces of labor have been wrung out by an expert laundress—as Agnes surely was, to have cleaned the clothes of miners.

I try to imagine what Agnes might have been making and doing, what produced the stains and tears. I wonder if Agnes Thies brought this apron with her to Alaska. Or did she make it herself from purchased textile? Does this apron also show evidence of other places, memories, and stains of favorite recipes that migrated with Agnes to Alaska before she became Bedrock Annie?

I envision Agnes cooking, moving with deft confidence around a small but efficient kitchen. Certainly, in Cleary at the turn of the 1900s, the array of groceries would have been limited. I imagine Agnes using wild harvested foods like salmon and nettles. And I imagine her cooking with vegetables easily transported in from Fairbanks or Anchorage and held for long periods, like storage cabbage, surely familiar to her before coming to Alaska. Cabbage is itself, of course, a migrant to Alaska brought by colonizers.

How might these ingredients, local and imported, have been imprinted on the apron here? Red cabbage might leave a pink or blue stain, salmon an oily mark of rich fat, nettle a grassy green. But such detail is hard to read—time has faded stains to the indistinguishable blotches visible now. Easily mistaken for delicate, this apron is worn and tough, as Agnes must have been, too, given her varied roles in a mining town. When looking at an object like this one, a record without a written history, I connect to a different way of knowing about a person and their experience, through my own associations and experiences sparked by close observation.

I cannot remember all the moments of wear which mark my apron, but I know that I have brought together ingredients and recipes from my childhood in North Carolina with new favorite foods here in Alaska. Nettle, a new ingredient to me since moving, is a green I harvest with tender appreciation each spring. And I swear that cabbage has never tasted as sweet as those large, purple heads grown by the Rempels that I purchase at the Anchorage Farmers Market. My Heritage apron holds stains of my past and my present, flavors of my upbringing merged with the harvest and gathering of Alaska. Green blotches of nettle and purple drips of cabbage juice, smears of graphite, burns from cooking and metal work, all these markings record my own makings in the kitchen, and studio makings, with my apron on.

First published in the Fall 2022, Issue No. 25 edition of Edible Alaska.