Rocks Into Food

A decade and a half ago, I came across an old rock cairn while scouting deer for the upcoming season. It was a few hundred feet from the summit of a mountain, and offered a good vantage, though it was partly hidden in mountain hemlock trees. At the time I didn’t know what I was seeing, but I was struck by how it appeared that someone had piled rocks atop each other even though they were mostly covered in lichens, moss, and crowberries. What really caught my eye, though, were the scattered bones and wolf scat. The rock formation smelled of wolf urine, which is muskier and sharper than that of a dog. The wolves appeared to be using the rock formation as a rendezvous site—a place where, as the pups are growing, the family rears and teaches them. During that time, the whole family transitions from being centered on a den to a more nomadic life. On the hike down I came across the remains of a doe the wolves had recently killed. It was hot out and her meat and organs were beginning to ripen. I guessed the wolves were nearby resting in the shade, so I didn’t stay long.

Last winter, Dave Kanosh, a Tlingit cultural bearer from Sitka, told me how his ancestors had built rock cairns in the subalpine and high in the mountains. He says many of these rock formations may date back to an ancient flood in which many died. Some survivors sought refuge atop mountains. The cairns were used as a calendar indicating when and where to harvest different foods. They were also used as memory devices to pass on stories. The two were equally vital for the survival of future generations.

“Rocks in those rock formations,” Kanosh said, “were used to help tell part of a story and each rock cairn had different stories.”

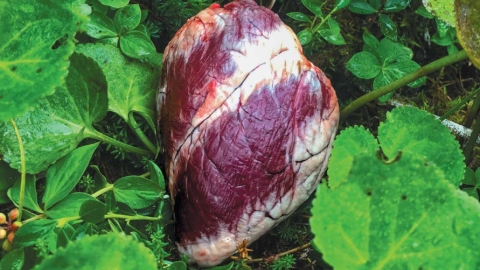

A few weeks after my first encounter with the rocks, I shot a small buck a couple hundred yards away from the cairn. Memories of past hunts on this mountain came back while I processed the deer as the crimson sunset faded to darkness. I’d made dozens of journeys up the mountain, starting when I was a kid. My brothers and I all killed our first deer on that mountain. During those times, I’d been given some of the stories and food I treasured most deeply. I paused from cutting the deer and reflecting to listen to the night sounds. I wondered if the wolves were nearby. I hadn’t seen any fresh wolf sign, which struck me as odd. With deer season open and increased human activity in the alpine, maybe the wolves had moved somewhere more remote. Years later, I’d learn how important salmon are for many wolves during the late summer and fall. The wolves had likely moved down to fish a creek with a good run of pink salmon a few miles away.

Kanosh’s insight into Tlingit cairns makes me want to know more about the person, or people, who built the rock formation, and the stories contained in those rocks. I also wonder about the wolves and what the rock pile represented to them. Maybe picking this spot was a random choice on the wolves’ part, but I have a hard time believing that.

Some biologists have pointed out that there are similarities in the social organization of wolves and hunter-gatherer cultures. When living in small familial groups, both wolves and people must intricately cooperate and bond to survive. That helps them both acquire food and defend their territory against intruders. Wolves, like people, teach their young how to hunt and what to eat. For instance, from what I’ve experienced, wolves only eat the heads of salmon. I imagine that older wolves teach the pack not to eat any other part of the salmon due to raw fish often having tapeworms and other organisms that are harmful.

The older I get, the more I see parallels between the stories we tell and the food we eat. We need food and stories to live. Some are good for us. Others are not. If they’re bad they can make us sick, crazy, and lead us in the wrong direction. There is an endless number of fad diets (including, of all things, a tapeworm diet) and dietary supplements that are basically snake oil.

As I wrote this column, I took apart the crib both my sons used in their infancy. A neighbor had gifted it to us, and by the time we outgrew it, it was largely held together by duct tape. We couldn’t gift it to another family, so I repurposed the crib’s wood to build shelves in our greenhouse. While I worked, my brother called. He mentioned that recently, during his eldest daughter’s last day home from her university spring break, the two hiked the mountain where I’d found the rock formation. After I asked, he described seeing the fresh trail of a lone wolf cutting through a snowy meadow.

I hadn’t been up that mountain for several years, but thinking about that wolf and the rock formation made me want hike it again. I’m not sure I could find the cairn, or that I want to. But in deer season, I’d bring my rifle along. Maybe I’d luck out and get a deer, or see wolves. Regardless, it would be enough to sit atop rocks and lichens, and remember all the stories the mountain had given me.