A Walk on the Wild Side

WITH STACY STUDEBAKER

A few snow patches remain on expectant brown hillsides as winter’s decline feeds spring’s new beginnings. Soon lush vegetation and a kaleidoscope of flowers will drape misty mountains and the mossy forests and island-studded coastlines of the Kodiak archipelago. On a mountain overlooking the city, a petite woman kneels with her forearms on the ground, carefully turning the lens of her camera. “Aren’t these just gorgeous!” she exclaims. Framing nature’s perfect flower arrangement in the viewfinder, she clicks the shutter.

Stacy Studebaker is a lifelong naturalist, adventurer, forager, photographer, teacher, and artist whose passion for Kodiak’s flora and fauna is legendary. A botanist who documented the diversity of plant life in the Kodiak National Wildlife Refuge, she self-published a richly photographed field guide called Wildflowers and Other Plant Life of the Kodiak Archipelago. She collaborated with artist Kay Underwood to produce three children’s books: Hey Bear Ho Bear, Octopus in the Outhouse!, and most recently, Beaver’s Song. Also, she co-created Kodiak Audubon’s Hiking and Birding Guide, an illustrated map of trails and birding places along the road system. The Alaska Conservation Foundation, the National Audubon Society, and the Kodiak National Wildlife Refuge have all honored her lifelong dedication and volunteer work in conservation, research, and environmental education.

For over 30 years, Studebaker has taught classes about the wild edible plants of Kodiak. Her offerings have ranged from semester-long courses to more condensed workshops and trainings.

“Stacy is so conscious of the earth and what it provides,” says Kodiak resident Carol Hult. “She knows the benefits of appreciating what’s there and using it in a way that nourishes us without harming what’s growing here.” For Hult, Studebaker’s classes forever changed the way she interacts with her surroundings. “These were plants that I walked by all the time, and it was the first real learning about them. Eating fresh, wild plants is the most nutritious thing we can do.” Hult also values Studebaker’s emphasis on a respectful approach for taking plants home and using them. “She gave us precepts for harvesting that inspired respect and gratitude.”

In addition to offering wild edible plant classes to the public, Studebaker trains the seasonal park rangers, biological technicians, interns, and volunteers at the Kodiak National Wildlife Refuge. “She goes into great depth about common plants, edible plants of Kodiak, poisonous plants, and recipes,” says Shelly Lawson, the education coordinator at the refuge and program lead for the Kodiak Summer Science and Salmon Camp. “An important part of the camp is to develop and appreciate a sense of place. We’re fortunate to have a botanist as knowledgeable as Stacy who provides training to our summer staff about the plants that campers see in and around their own backyards.” Lawson hears from parents that the kids often teach their families what they learn about the plants and wildlife in Kodiak, continuing to pass on the gifts of knowledge and appreciation for the environment.

“She’s not just a teacher. She walks her talk and is quite a cheerleader for many things, especially the plants,” says Marion Owen, a professional photographer and writer from Kodiak who runs the blog Lagniappe. “There are people who have a phobia of something if it doesn’t come from a store, but really, it’s the other way around,” she remarks. “We should trust the wild plants and be skeptical about what we see in the stores.”

As a professional photographer, Owen is thankful for learning useful field techniques from Studebaker. “She also instilled in me the visual tool of how to see, how to scan, and have this mental image ready, and to look for it out there, whether it is a bear, fox, or moonwort,” she comments. “It takes a lot of focus and concentration to be in the moment, in the present. It’s a very powerful tool that I learned that I use all the time.”

Spring bounty

Going on a walk with Stacy Studebaker is an immersion in the world of plants, birds, and other creatures which have their own separate stories that link to each other and to the landscape. Our spring adventure takes us to a variety of ecosystems in search of plants for dinner. “The knowledge of what’s edible is so important,” she remarks as we pass by a crystalline stream. Over the years, she has noticed that young mothers and fathers come to her classes because they want to connect their children with nature. “There’s a movement among the younger generation to become more self-reliant.” Learning the skills of identifying, gathering, and eating local plants also nurtures opportunities to spend time together as a family.

“Speaking of edible, look at what’s down there,” she says, pointing. Fiddleheads peek up from mounds of brown leaves. These glowing green fern babies are edible when the tiny fronds are still tightly curled spirals within a spiral. “They are so tasty but they are one of the most labor-intensive wild plant foods since you have to take all the little scales off,” she warns. “It’s important to remember to only harvest as much as you’re willing to process because cleaning them will take twice as long as gathering them.”

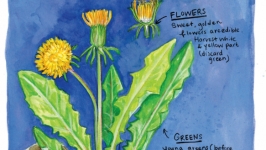

After collecting a modest quantity of fiddleheads, we continue foraging. Remarkably, our timing is perfect for a spring harvest yielding sizeable plants that are not yet bitter. We admire the multitude of edible plants that surround us, such as feathery purple-red fireweed shoots in a meadow, bright spruce tips in the forest, and succulent beach greens and goose tongue at the ocean’s edge. We munch on aromatic young stalks of cow parsnip, known locally as pushki, and scientifically as Heracleum lanatum. Touching or harvesting pushki on sunny days should be avoided because phytotoxins in the plant can cause skin rashes, burns, and blisters. Being aware of potential allergic reactions is also critical whenever interacting with a plant for the first time. On this overcast day, Studebaker demonstrates how to scrape the hairs off before we can safely give them a nibble. This abundant spring vegetable is especially an important traditional food staple for the Sugpiaq people who are the indigenous inhabitants of the Kodiak region.

The fresh springtime air fills our lungs with the fragrance of reawakening plants. One familiar scent caught my nose and I searched for the source—alder catkins, cones, and sticky, recently opened leaves. The edible catkins are unpalatable and considered a last resort survival food for humans. Yet Studebaker acknowledges the value of this plant as food for other creatures. “The tiny little seeds help to sustain our local resident population of songbirds,” she says. “Spruce cone seeds and alder cone seeds in the wintertime are so important for the birds.”

Endless gifts of learning and teaching

All her life, Studebaker has been surrounded by natural wonders. She grew up on the beach in California and worked as an environmental educator and national park ranger in Yosemite Valley. When she became a ranger in Glacier Bay National Park, she fell in love with Alaska. She went to the East Coast for graduate school at Antioch University in New Hampshire for a double degree in Secondary Education and Environmental Education. “I wanted to come back to Alaska and teach in a coastal community,” she recalls.

In 1980, she moved to Kodiak and taught high school biology, earth science, botany, and environmental studies. After more than 20 years of teaching, Studebaker has seen her former students grow up, and some even have children of their own. “It’s a really neat feeling to be in a community where you’ve been a teacher. You have connections with families,” she remarks. “Many of my former high school students have become doctors. And, one is my doctor today!”

Even after retiring from teaching, educational adventures continued to surface in Studebaker’s life. In 2001, she discovered the body of a gray whale washed up on the beach. Seeing a silver lining ever present in the cycles of life and death, Studebaker embarked on an incredible journey to honor the whale in a visionary and scientific way. She orchestrated countless volunteers, scientists, and agency partners to first bury the whale on the beach for four years, exhume it, then painstakingly rearticulate the 37-foot-long skeleton. The project witnessed the rebirth of a whale carcass into an educational installation, suspended from the ceiling of the great hall in the Kodiak National Wildlife Refuge visitor center. The whale saga comes full circle as an epic educational gift from a retired science teacher—a testament to Studebaker’s steadfast leadership and the collective power of community.

The world of circles

Studebaker’s fascination with circles is apparent in her mandala artwork that combines photography with meditative arrangements of items she finds in nature. The mandalas reflect both season and landscape, ranging from mosses and lichens, and seashells and pebbles, to flowers and berries and plants. “The spirit of the world works in circles and all things try to be round,” she says, quoting a passage from Black Elk Speaks, a book she read in the early ’70s. These concepts have resonated in the background of her mind ever since. The study of Buddhism has also been an influence in Studebaker’s life. “Mandalas are a focal point for meditation. I see mandalas when I close my eyes at night. They move, they spin. Anyways, my life is one big mandala.”

Back in the kitchen, we gather to assemble our discoveries into dishes. “This would have been a lot of vegetables to grow!” remarks Stacy as we put together a salad of salmonberry flowers, willow leaf, beach greens, and other plants drizzled with a cottonwood bud olive oil and vinegar dressing. Spruce tips infuse our water. Rose petal butter crowns the bread.

Many of the recipes Studebaker uses in her own kitchen are innovations from students in her wild edible plant class over the years. She designed the final exam of her class to be a wild edible gourmet potluck. Everyone brought to the potluck a dish that included wild plants they harvested. “I encouraged people to experiment with spruce tips, and one of the students came up with the idea of roasting them and adding them to cornbread,” mentions Studebaker. Other creations included salmon patties with beach lovage, sourdock salad, spring rolls, elderberry flower muffins, and more. “Yummers, yummers, yummers!” she says with a laugh.

Wild plant pizza is one of Studebaker’s signature wild food creations that meditates on different combinations of foraged, fished, and hunted foods delivered on a contemporary food platform. Our spring pizza includes nettle pesto from the freezer as the sauce. We layer fiddlehead and fireweed shoots in a radial pattern, followed by a sprinkling of spruce tips and shredded cheese. Smoked salmon adds a pop of color. A tasty wild parsley called beach lovage garnishes the center. The final assemblage of ingredients results in a circular piece of edible art—a wild plant pizza mandala.

The hallmark of a true teacher is a generous effort to help the learner see, understand, and be open to new experiences and ideas. Studebaker’s infinite curiosity and boundless energy have inspired many to deepen their connections to Alaska’s emerald isle and to embrace the infinite circles of our universe.