Food for the Finish

Three women mushers on fuel for body and spirit

In the food world, “mush” is usually pejorative. Mush enters the English language in the 17th century as a variant of mash. The word calls to mind gray, gooey bowls of poorly cooked porridge, piles of mealy fruit, and plops of overcooked green beans. But the word mush also unlocks a whole other world of competitive dog racing. Mush in this sense calls forth a whole other set of images: powerful dogs, and bundled mushers braving harrowing conditions across expanses of ice and snow.

Most food writing about mushing is, understandably, focused on dog food. The images of sled dogs sprinting across the snow capture the imagination— I even had a stuffed sled dog as a kid growing up in the North Carolina foothills which rarely see snow. Sled dog food is, in fact, mush, or at least mushy, usually a high-calorie slurry of kibble and water and sometimes a treat of a scrap meat soup. The training and competing diets of the human mushers, though, is delightfully eclectic and delicious.

Historically, Alaska Native peoples used one or two dogs for running goods. The origin of what is considered dog mushing today, with big teams of dogs hauling large sleds, is French-colonized Canada, according to Anchorage Museum Senior Curator of Alaska History & Indigenous Culture, Aaron Leggett. Indeed, the term “mush” is derived from the French “marche/marchons,” an imperative meaning walk or advance, used to command a team of dogs.

Spread to Alaska through advancing colonization prompted by discoveries of gold and other resources, modern dog mushing by the mid-19th century became a critical means of transporting goods and traveling between communities in winter. As aircraft became more available throughout Alaska in the 1930s, and snow machines were popularized in the 1960s, mushing transitioned from primarily a mode of travel to a competitive sport, first with shorter sprint races and then with long distance races. The first Fur Rondy sprint race was run in 1946 and the nearly 1,000-mile Iditarod was first held in 1973.

The Anchorage Museum’s exhibition, Extra Tough (up through summer 2021), showcases an incredible image of four-time Fur Rondy winner Roxy Wright with her dogs in 1983. Women like Roxy have competed in professional races since early in race history, and have won, hence the T-shirt slogan, “Alaska: Where Men are Men, and Women Win the Iditarod.” Still, women mushers remain a fraction of the racers competing in Alaska—just 33 percent of the 2019 Iditarod entrants.

Three Alaskan women mushers share their favorite foods and food stories for subzero temperatures, variable conditions, and simply delicious eating from Alaska’s bounty.

“I had to learn to eat the hard way,” says Libby Riddles, the first woman to win the Iditarod. Riddles came to Alaska from Wisconsin at age 16 in 1972, and immediately fell into mushing. Riddles blazed to the 1985 Iditarod finish in Nome in 18 days, 20 minutes, 17 seconds, racing through a fierce snowstorm, and leaving her competitors hours behind. For this famed race, Riddles had her trail food down to an art, but that came after some trial and error. “Have you ever tried to dig into a 5-pound Tillamook when it’s 20 below zero?” she asked wryly. “Just shatters everywhere.”

Food must be prepared for brutal temperatures, and the musher must be well fed. Riddles says when she first started training, she would not get enough to eat while running the dogs—maybe just a few spoonfuls of peanut butter—leaving her faint by the end of the day when tending to dogs was first priority. She learned quickly to fuel up wisely for her athletic days of training and racing. Riddles says the “perfect thing” before a big day out training is what she dubs a Teller-style breakfast, named for Teller, Alaska, where Riddles lived for a period. Eating this significant breakfast of a stack of sourdough hotcakes, one or two eggs, bacon or leftover fish or moose steak might seem to non-mushers like a whole day’s accomplishment in itself. But, such a high-protein meal is necessary for the hard work of mushing in cold temperatures for hours.

When out on the trail for the long-distance races Riddles is famous for winning, such a breakfast is not easy to whip up. Food for mushers and dogs is dropped in advance at checkpoints and left outside, portioned in Tupperware and Ziplocs and kept in paper bags along with dog food and extra goods that might be needed, like dog booties and batteries. While the cold outdoor temperatures keep the food from spoiling, the frigid conditions also freeze most food solid as it awaits mushers for days. So, meals and snacks must not only provide the musher with adequate calories, they also must satisfy the need to prepare and consume them in subzero conditions.

Moose meat strips cooked in bacon fat provide high protein and high fat energy for long races. Ziplocs of frozen peas and berries kept in jacket pockets can be sucked and consumed on the trail and provide a bit of liquid and hydration. Eating these kinds of jacket-packed snacks, which Riddles calls “pocket food,” like nuts or frozen meat, right before a checkpoint is very important to have enough energy to attend to the dogs and chores first. Musher food is sometimes warmed up in plastic bags alongside the dog food. As Riddles says, “I think the best meal I have had in my life was sitting on my dog food cooler eating a hot fettuccine alfredo at 20 below on the Yukon River.”

Riddles finds sweet foods largely unappealing while racing. “I could beat anybody who has eaten candy bars. I don’t see how people do that with that kind of snacky sweet stuff.” She does, however, have two particular indulgences. For Riddles, coffee is essential. “I mean I eat pretty good food, but I love coffee. I love good coffee. I was one of the first people knocking at the door at Café Del Mundo—actually I think I had them sending me bush-shipped coffee up to Teller, when I lived up there.” Riddles would make a strong pot of half-caffeinated and half-decaffeinated coffee (too much caffeine could cause an energy crash), mix it with a little brown sugar and cream, and freeze it flat in Ziploc bags to nibble on-trail or warm up at checkpoints to drink (recipe inspired by Riddles follows). For longer races, she would also spread Nutella onto a frozen croissant for a true treat. “They freeze hard enough, they don’t squish too much,” Riddles says, “but they stay just pliable enough to eat. So uptown.” She laughs.

For the most part, Riddles believes, “If you pay attention, you can tell what’s best for your body and in different conditions,” and that means eating clean, whole foods, and eating the food of the place where you are. “The more you eat off the land, the more you are a part of it,” she says. Riddles, who lives in Homer, Alaska now, clearly maintains passion for cooking with local ingredients, making foods like salmonberry kombucha and homemade raspberry jam on sourdough waffles. Her approach to fueling up with intention helped propel her through her career and eventual induction in 2007 into the Alaska Sports Hall of Fame.

For Roxy Wright, the sustainable, wild harvest of Alaska is fundamental. “Being Alaska Native,” she says, “our lifestyle still revolves around the hunting and gathering of our natural, Native foods.” She is the only woman to ever win the Fur Rendezvous Open World Championship Sled Dog Race—and she won it four times. Her father Gareth Wright was also a winning dog musher, and he taught her “an all-inclusive lifestyle of the dogs, the food gathering, and the way we interact with the world.” Roxy Wright’s most recent win in 2017 made history, when at age 66 she came out of retirement to zip to the finish, 24 years after her third victory. Wright now lives in Fairbanks and is officially retired, but still helps her niece run her dogs.

As a sprint racer, Wright focuses on foods that sustain and keep her fit and healthy. Short sprint races happen in a few hours at most, so snacking on-trail would distract from the focused race. But, training and working with dogs demands endurance and energy. Wright says, “My family has always eaten pretty healthy,” relying mostly on food harvested from the land like moose meat and salmon, with vegetables or greens. She goes hunting and harvests fish each year, she says. “I hardly ever buy meat from the grocery store.” She far prefers moose to beef, preparing moose ribs, steaks, burgers, stews, and also frying the heart in bacon grease or baking and stuffing. Before a day out training, a hearty bowl of oatmeal and salmon fuels Wright. For a snack, she may take salmon or moose strips she has prepared. The high levels of fat keep them from freezing solid in cold temperatures. Her larder is filled with canned and dried harvest, and her freezer well stocked to fuel her and her family.

For Wright, the relationship to the land is intrinsic. “All the animals and earth are all inter-related. We need to respect the bounty of the land and the relationships so that we are not wasteful and that we are aware of our actions and what we do—not only us but where we are on the land, and who we’re with, whether it be animals or people.” One way she expresses this relationship is through what she creates in and shares from her kitchen.

Given Wright’s connection to the land, it’s no surprise that berries come up again and again. She picks with her family, and often runs into friends or family when out picking alone. Wright glows when she says, “There is nothing more spiritual than being in a berry patch.” Wright gathers 10 gallons of blueberries and 10 gallons of lowbush cranberries a year, more than she needs for herself. She shares the bounty with her family, making pies, sauces, jams, and a savory cranberry and rose hip ketchup (a recipe inspired by Wright follows). “It isn’t so much the food as just food for your body, but the spiritual connection with family and the land that is so deep and important.”

Wright’s remarkable career is, as she puts it, a “fairy tale,” coming out of retirement to not only win the Fur Rendezvous, but also be the oldest person to ever do so. For Wright, in addition to sustainable food, fuel comes from doing what you love. She advises, “If you are going to have life’s work, find something you are passionate and love to do. That way it is never drudgery. It’s fulfilling each day. I encourage young people, old people, middle-aged people, all people, no matter gender, race, or whatever, don’t be afraid to dream.”

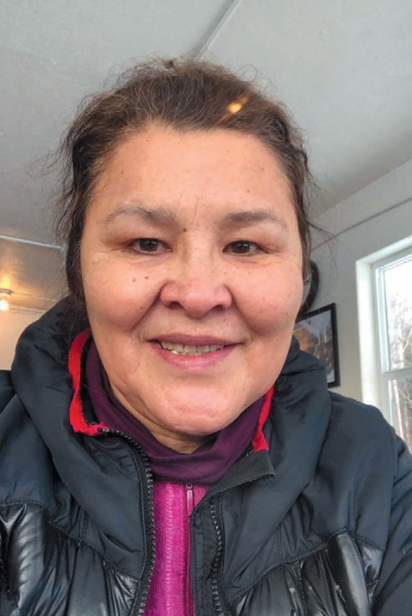

Evelyn Beeter is a leader—President and CEO of Mt. Sanford Tribal Consortium, Board member and Treasurer of Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium—and a winning, competitive dog musher. Beeter says the dogs keep her busy life balanced. “They keep me centered. They bark a greeting to you and you can’t help but be happy.” Beeter grew up around mushing. Her mother raced, running the Yukon Quest four times by age 58 and sprint racing in other competitions alongside Roxy Wright. By high school, Beeter won the seven-dog class in the Junior World Championship in Anchorage in record-breaking time. She has taken a few breaks from competition, but always comes back to mushing.

A long day of training starts with a hearty bowl of oatmeal or Cream of Wheat with added fat like coconut oil to help keep warm in the cold. A snack when traveling might be a sandwich prepared with jerked salmon strips and pickles. Like Wright and Riddles, Beeter relies on high protein, high healthy-fat foods to keep her warm and energized. As she says, “Don’t use the sugar stuff—you run out of energy too quick. The proteins and oils really sustain you.” She particularly loves salmon strips, especially salmon from the Yukon for their high oil content, which she likes to accompany with pilot bread. Wild harvested berries also feature in her kitchen in all sorts of jams and jellies, including a cranberry and banana jam, a specialty of hers.

Each year she takes two weeks off work to go moose hunting, a time that, like mushing, deeply connects her to the land. “It’s the best time just to be out there, listening, being connected and soaking it all up,” she says. While processing the moose is real work, “while you are out there, you don’t have to worry about anything.” Beeter turns her hunt’s harvest into a variety of delicious meals. She makes broth with the moose bones for a rich, nourishing base upon which to build a soup or stew. She makes a moose and barley stew, which she will have as a special treat with a slice of bread slathered in butter. She also will simmer moose meat with beans and vegetables all day to make a chili, a perfect warmup for a day running the dogs.

After hours out in the cold, though, nothing beats a cup of tea. Her mother served a meal of tea, baked fish, and warm biscuits, Beeter recalls with tenderness. Beeter has a passion for Earl Grey tea. A strongly brewed cup warms and soothes after a hard day’s work. (This particular favorite of Beeter inspires an energy cookie recipe below.) In the deepest, most cherished way, true comfort comes in the relationship with the land, and the traditional foods which can be harvested from it. As Beeter says, “The land sustains us and the Copper River sustains us. We’re part of it, so that’s where our food comes from. You need to take care of your land, and what you harvest so that they keep coming back. When you get your food and prepare it, you must take care of it in a good way. You must respect it and others.”

Nourishment

For these three mushers, eating is not just about calories or energy. If it were, they might discuss energy goo and power bars. The essential energy foods of Riddles, Wright, and Beeter are salmon, moose, and berries. Sustenance comes, too, from running dogs, working hard, and being out in the natural world. For these hearty, winning women, food is about a loving relationship to one’s own body, to one’s family, and to the land. Whether a meal is prepared with the ample time and the amenities of home, or taken as a quick snack while out training, the foods of these champion mushers are gathered, prepared, and consumed with care and appreciation. Their food fuels the body and spirit, a true kind of nourishment.