From Pariah to Posh

In 1740, English judge John Gonson declared, “Nothing is more Destructive either to the Health or Industry of the poorer Sort of People, on whose Labour and Strength the Support of the Community so much depends, than the immoderate Drinking of Geneva.” Geneva meant gin, taken from the Dutch “jenever” for the juniper berries that flavored the distilled alcohol.

In the 1953 novel Casino Royale, another Englishman, James Bond, orders a Vesper. “Three measures of Gordon’s [gin], one of vodka, half a measure of Kina Lillet. Shake it very well until it’s ice-cold, then add a large thin slice of lemon peel.” This particular recipe is coincidentally the first appearance of Bond’s preference for shaken rather than stirred cocktails.

Between Gonson and Bond are two centuries and several cultural revolutions in drinking habits. Gonson’s attitude towards gin reflected those of the English elite in his time. Bond, himself an elite Englishman, reflected attitudes much removed from his far predecessors. The road from one extreme to another wound through the intervening decades, a path from derision to decadence, from pariah to posh. And along the way, it passed through Alaska.

During the first half of the 18th century, England was caught in a widespread moral panic: the extreme popularity of gin with the poorer classes. It was the great English Gin Craze. As with other moral panics—from heavy metal to video games—fears over a changing society lay at its root. Gin was the preferred drink of laborers and others at the lower end of English society. As one magazine declared, the prevalence of gin might end “all Voluntary Submission” by the lower classes and place “every Man to an Equality with his Master,” a terrifying scenario for the nobility and gentry.

By the early Victorian period, ornate gin palaces had replaced the dreary shops of the English homefront a century prior. Gin had become a fashionable if still edgy commodity. The old connotations still held amongst a large proportion of the populace.

Gin was cheap, could be manufactured domestically, and was thus widely available, in proper shops and via more transient options. In 1736, there were an estimated 120,000 gin shops in England, an “enormous Fund of Corruption, Vice and Debauchery” as described by a contemporary newspaper. But just as often, it was offered from wheelbarrows, baskets, and boats, all trying to evade taxation. Portsmouth records from 1737 describe a “Moveable Hut or Hovell” that dispensed “Retail Geneva.” Imagine modern food trucks or farmers markets focused on selling gin. During this period, gin also became a significant export to the American colonies.

People did not deplore gin simply because it was a spirit. Other alcoholic beverages were considered honest beverages that, if anything, increased the vigor and vitality of the nation. Engraver William Hogarth best summarized the dividing perspectives in a pair of prints first published in 1751. In Gin Lane, the buildings crumble around the remaining businesses: a pawnshop, coffin maker, and distillery. An intoxicated mother drops her baby towards the pavement, an open-mouthed scream on the child. Another nickname for gin was Mother’s Ruin. In Beer Street, the streets are clean, and construction carries on in the background. The populace appears healthy and industrious.

Between 1729 and 1751, Parliament passed five major acts meant to curtail gin consumption. They tried taxes and licenses. They regulated the distillers. They even tried informants with bounties for the successful seizure and conviction of illegal retailers. None of it worked. Demand was too high, and the few informants risked a mob reaction. The gin craze diminished only when the grain supply decreased, increasing the cost to the point that consumers sought other intoxicating options.

The rehabilitation of gin was slow. As a tipple best associated with Britain, that process unsurprisingly included empire building. In 1765, Britain invaded India, where more soldiers died from malaria than battle. Quinine, a cinchona tree extract, was the most effective malarial treatment available. The bitter extract was mixed into a liquid, producing a tonic water. Soldiers added sugar and gin to make the medicine palatable, birthing a new cocktail. Accordingly, the first known print reference to a gin and tonic was in an 1867 issue of an Anglo-Indian magazine, about demands for the highball at a horse race.

By the early Victorian period, ornate gin palaces had replaced the dreary shops of the English homefront a century prior. Gin had become a fashionable if still edgy commodity. The old connotations still held amongst a large proportion of the populace.

A true marker of changing attitudes came with the British military. In 1854, an army physician ordered all troops under his responsibility to consume quinine during an expedition up the Niger River. Quinine had been informally promoted for decades, but there became an official requirement. Gin likewise became promoted, especially in the British Navy, where it was the drink of choice for officers. The old slurs finally faded away.

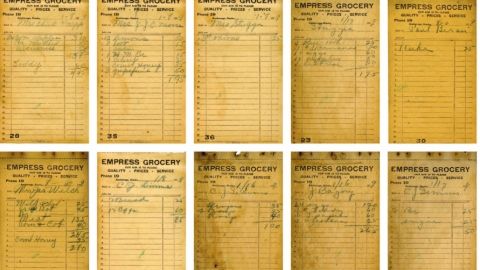

Gin likely first appeared in Alaska in the late 18th century, brought north by traders or British explorers, but its presence became notable during the gold rushes a century later. Liquor was an essential item carried by prospectors and those who prospected the prospectors. At the Klondike gold rush’s inflationary peak, a shot of gin cost around a dollar. A couple of years later, given more robust supply chains, a full bottle cost $1.50 in Skagway.

Author Rex Beach turned his experiences during the Nome gold rush into a novel, The Spoilers, a bestseller adapted into a movie no less than five times. He wrote, “Rarely was the choice of potations criticised” before mentioning gin by name. Still, evidence suggests that gin lagged behind other potent potables in popularity. Atlin, in British Columbia, was another gold rush boomtown. During the winter of 1898 to 1899, as supplies dwindled, its saloon was down to “only two bottles of gin as stock in trade.” Modern archeological investigations at Skagway found far more beer and other liquor bottles than gin.

Prohibition was the next major shock in the history of gin. As legitimate American distillers closed, the black market took over, producing gut-wrenching facsimiles that begged for flavorful additives. The popularity of mixed drinks boomed. Even bootlegging gangster Al Capone got into the ginger ale business. With the taverns closed, people made the drinks at home, building wet bars that became the center of local social lives.

The defining liquor of Prohibition was not whisky or vodka but gin, now the glamourous choice. Jay Gatsby, the titular millionaire of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s 1925 novel The Great Gatsby, drank Gin Rickeys. One recipe played off Alaska nostalgia. The kids who read dime novels of the gold rushes became adults who watched movies like The Spoilers and drank Alaska Cocktails. This three-ingredient drink variant was golden from yellow chartreuse reminiscent of the fever that drove the stampeders mad, and flavored further with a dash of orange bitters.

When Prohibition ended, the desire for mixed drinks remained. Wet bars likewise went legitimate and entered the mainstream. They remain a relic in many midcentury homes, including in Anchorage.

Apart from legality, the primary change for gin was quality. Out were back-alley homebrews and bathtub rotgut. In were proper distilleries that emphasized purity and flavor. That trend carried gin to Alaska again, with manufacturers like Port Chilkoot Distillery in Haines, Amalga Distillery in Juneau, and Uncharted Alaska Distillery in Ketchikan. Instead of chartreuse, they offer products infused with familiar Alaska ingredients, like spruce tips, rhubarb, and devil’s club.

The ingredients, context, and social standing of gin evolved slowly over more than three centuries. A London commoner of the early 18th century, familiar as he was with bargain-priced gin, would not recognize the more palatable version available today. That same commoner would admittedly also be utterly befuddled by James Bond. For all that, the concept and relative simplicity of gin have remained true throughout the years, with an admirable constancy, the better for all who thus imbibe.

Originally published in Edible Alaska issue no. 34, Winter 2024.